Sir Joshua Reynolds: Why 'the greatest portrait artist England has ever seen' is the true heir to the Old Masters

It wasn’t merely brilliant brushwork or sparkling colour that made Sir Joshua Reynolds one of England’s greatest portraitists. His talent for friendship nurtured his extraordinary career, says Susan Jenkins.

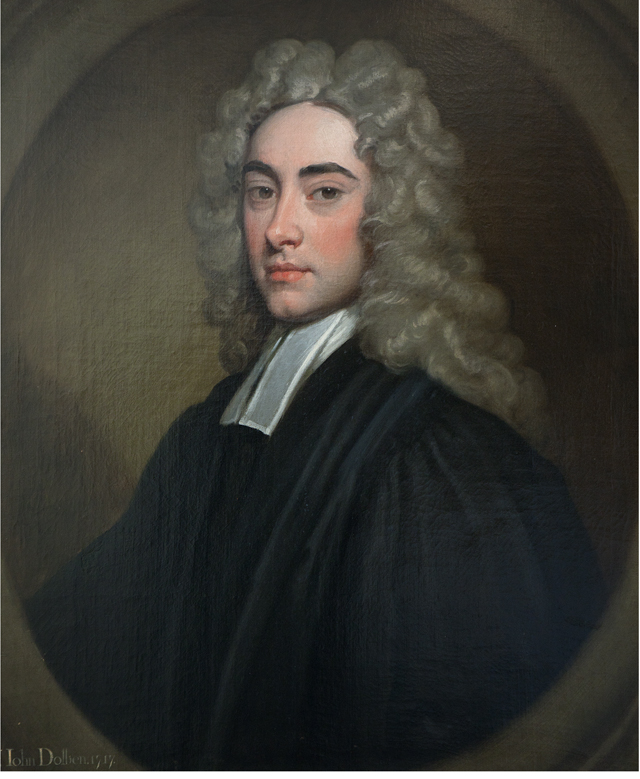

Little in Sir Joshua Reynolds’s early days suggested his works would one day grace the walls of most museum and country-house collections in the UK. Yet the son of a Devon clergyman — he was born in Plympton, Devon, on July 16, 1723 — shrugged off his modest beginnings as a painter in Plymouth Dock (now Devonport) to become the greatest portrait artist England has ever seen.

A founder and the first president of the new Royal Academy of Arts in 1768, he was knighted by George III in 1769, lived and worked in a magnificent house in Leicester Fields (now Square) attended by servants in livery and was eventually appointed Principal Painter to the King in 1784. This year his legacy is being felt again in his home county: ‘Reframing Reynolds: A Celebration’ is at The Box, Plymouth, Devon, until October 29.

Reynolds’s extraordinary rise to fame was testament to his unique skills. These were a rare combination of brilliant brushwork, an innovative and intellectual approach to his art and an ability to make friends and inspire loyalty in the right places.

Although his sister Fanny, his sometime housekeeper, called him a ‘gloomy tyrant’, his pupil James Northcote wrote fondly: ‘I know him thoroughly and all his faults, I am sure, and yet almost worship him.’

The life and times of Sir Joshua Reynolds

- 1723 Is born in Plympton, Devon

- 1740–43 Is apprenticed to portrait painter Thomas Hudson in London

- 1749 Meets Commodore Augustus Keppel and joins HMS Centurion’s voyage to the Mediterranean

- 1749–51 Spends two years in Rome studying the Old Masters; an illness leaves him partially deaf

- 1752 Establishes portrait practice in London with his lifelong studio assistant Giuseppe Marchi

- 1750s Paints portraits of the Dukes of Devonshire, Grafton and Cumberland

- 1759 Publishes his first writing on art in Dr Johnson’s The Idler

- 1760 Buys a large house on west side of Leicester Fields and builds a studio there

- 1768 Is elected first president of the Royal Academy, which opens the same year

- 1769 Is knighted by George III

- 1779 Lectures and writings on art are published as Discourses

- 1781 Tours Europe

- 1783 Paints portrait of Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse

- 1784 Becomes Principal Painter in Ordinary to George III

- 1787 Paints portrait of Lord Heathfield

- 1789 Loses sight in left eye and retires

- 1792 Dies; is buried in St Paul’s Cathedral

Arriving in London, in 1740, as an apprentice to the fashionable Devon-born portraitist Thomas Hudson, Reynolds returned home to the West Country in 1743. Ten years later, he set up his own studio back in the capital, following a career-changing passage to the Mediterranean with Commodore Augustus Keppel (1725–86), son of the 2nd Earl of Albemarle, and a period of study in Rome.

An early portrait dating from this time depicts Catherine Moore, soon-to-be wife of his future fellow Royal Academician the architect William Chambers. Painted in about 1752–56, it is now part of the Iveagh Bequest at Kenwood House, London NW3.

Once established in the capital, Reynolds painted dramatic portraits of members of the nobility, outshining the stiffer, more polite works of his rivals, such as Scottish artist Allan Ramsay. His first full-length, heroic portrait, painted in tribute to Keppel in about 1752, now hangs in the National Maritime Museum. The work confirmed him among his contemporaries as ‘the greatest painter that England had seen since van Dyck’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Royal patronage followed swiftly and, in about 1758, Reynolds painted a majestic full-length portrait of William, Duke of Cumberland (1721–65), third son of George II, also known as the ‘Butcher of Culloden’. The dignified image of the famously fat duke supported the artist’s reputation for combining truth with fiction. One critic expressed surprise to discover that Reynolds painted ‘the exact features’ of his ‘half-witted’ acquaintances, so ‘every muscle in their visage appears to be governed by an enlightened mind’.

Reynolds saw himself as the true heir to the Old Masters, such as Titian, van Dyck, Rubens and Rembrandt, aiming for ‘grand effects’ in his portraiture. Unfortunately, his paintings deteriorated during his lifetime because of his experiments with rich colour and impasto using unorthodox mixtures of wax and varnish. One critic remarked that his works resembled ‘rotten eggs against barn doors’.

Despite this, Reynolds remained in demand due to his dramatic, innovative compositions and sensitive modelling. His studio sitters books show that, at the height of the season, he and his assistants regularly accommodated five or six sitters a day for an hour at a time. Among them were actors such as David Garrick, who was represented ‘between Tragedy and Comedy’ in 1761, and Mrs Sarah Siddons, an actress Garrick employed at the Drury Lane Theatre, depicted as the ‘Tragic Muse’ in 1784. More notoriously, Reynolds also painted popular actress-courtesans, such as Fanny Abington, née Barton, who is portrayed as Thalia, the Comic Muse, in about 1768 and again as ‘Miss Prue’ in William Congreve’s 17th-century play Love for Love a few years later.

No matter the questionable background of some of Reynolds’s sitters, aristocratic families and Society ladies beat a path to his door, attracted by his royal patronage and the quality of his work. Foremost among these was the fashionable Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, who sat for him several times, most famously for a charming portrait where she is depicted playing with her daughter Georgiana. Equally striking is the intimate portrait of the three Waldegrave sisters, about 1781, commissioned by their uncle, the collector Horace Walpole. The fashionable young women are seated at a table engaged in domestic pursuits, in a ‘conversation piece’ that invites us to admire both them and their artistry.

Although successful, Reynolds was not immune to disappointments. He complained that the post of Principal Painter to the King, which he took in 1784, was ‘a most miserable office… reduced from 200 to 38 pounds per annum, the King’s Rat catcher I believe is a better place… and I am to be paid only a fourth part of what I have from other people’.

He was also unsuccessful in his ambition to be respected as a ‘history painter’, rather than as a portraitist, despite the patronage of Empress Catherine II of Russia. The Empress commissioned one of Reynolds’s largest and most ambitious works, The Infant Hercules, in 1785, now in the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. The plump infant Hercules is lying in his cradle attempting to strangle two poisonous snakes sent by the goddess Juno. Critics were not impressed and Walpole commented snidely: ‘I did not at all admire it… Master Hercules’s knees are as large as, I presume, the late Lady Guildford’s.’

Nonetheless, Reynolds’s portraits of children, or ‘fancy pictures’, were very popular, largely because of their sentimental nature. The portraits of Miss Crewe and her younger brother John ‘as Henry VIII’, painted in about 1775, demonstrate the originality of Reynolds’s handling and his observational skills. His most successful child portrait is a touching tribute to three-year-old Penelope, daughter of Sir Brooke Boothby, 7th Baronet, who died a few years after the work was delivered. The painting brims with charm and personality, evoking the delight Reynolds took in such sittings. According to Northcote, the artist ‘used to romp and play with [the children] — but while all this was going on, he actually snatched these exquisite touches of expression which make his portraits of children so captivating’.

Reynolds’s clubbability and talent for friendship made him the natural artist to supply group pictures of his peers. The two portraits painted in 1777–78 of members of the Society of Dilettanti, whose numbers Reynolds had joined in 1766, are outstanding for their animation and sensitive characterisation. The works depict the most important artistic patrons of the age, including Sir William Hamilton, husband of Nelson’s lover, Emma, who is shown presenting his book of ancient vases, surrounded by fellow Dilettanti members enjoying copious amounts of vintage claret.

Reynolds’s works now enrich our national collections, as befits the greatest Society portraitist of his age. He was prolific and popular and his best paintings sparkle with life and colour, capturing the brio and personality of his sitters. He oversaw a renaissance in British art, guiding royal taste and fostering the next generation of artists through the Royal Academy of Arts.

His friend Edmund Burke, who was with him on the night he died, pronounced him ‘one of the most memorable men of his Time… In Taste, in grace, in facility, in happy invention and in the richness of Harmony of colouring, he was equal to the great masters of the renowned Ages’. The painter’s achievements were commemorated in a magnificent funeral at St Paul’s Cathedral, a fitting tribute to a true Master of the Arts.

‘Reframing Reynolds: A Celebration’ is at The Box, Plymouth, Devon, until October 29, supported by the Weston Loan Programme with Art Fund (www.theboxplymouth.com)

South Sea tales: the Polynesian sitter

Reynolds painted some of the most memorable portraits of the age, including the great full-length Portrait of Mai (formerly Omai), in about 1776. This striking work was saved for the nation this year, in a joint acquisition by the National Portrait Gallery, London, and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, US.

Mai came from Tahiti and arrived in Britain in 1774, with Capt James Cook. The turban and flowing robes of Reynolds’s portrait are imaginary, but contemporaries considered the likeness to be ‘very good’. Mai attracted considerable attention in England, but decided to return two years later to Tahiti, where he remained and died soon afterwards. His life and adventures inspired a play, Omai, or a Trip round the World, which was first performed in 1785 at Covent Garden.

My Favourite Painting: Ashley Hicks

My Favourite Painting: Rebecca Stott

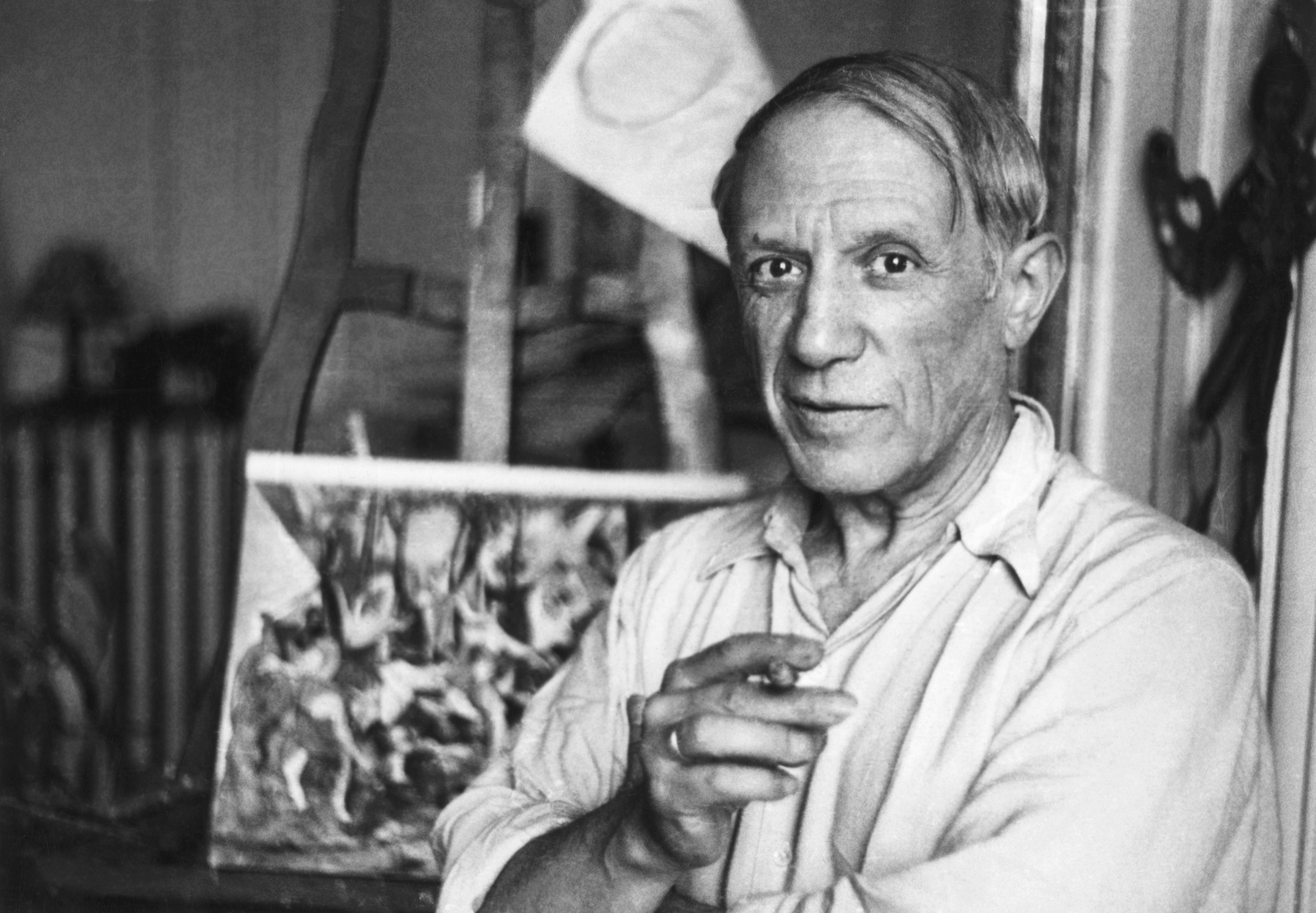

The writer chooses an unusual image by the iconic Spanish artist Pablo Picasso.

Credit: Richard Cannon

My Favourite Painting: Richard Coles

Richard Coles chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

My Favourite Painting: Barry Humphries

Barry Humphries chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

My Favourite Painting: Michael Sandle

Sculptor and draughtsman Michael Sandle chooses a haunting Arctic image by Caspar David Friedrich.

My favourite painting: Nicola Shulman

Nicola Shulman chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.