Paul Cézanne: Stubbornness, single-mindedness, and the struggle to capture sensations on canvas

Determination, rather than innate brilliance, made Paul Cézanne a great painter, but he was always more at home in his native Provence than in the Parisian art world says Caroline Bugler.

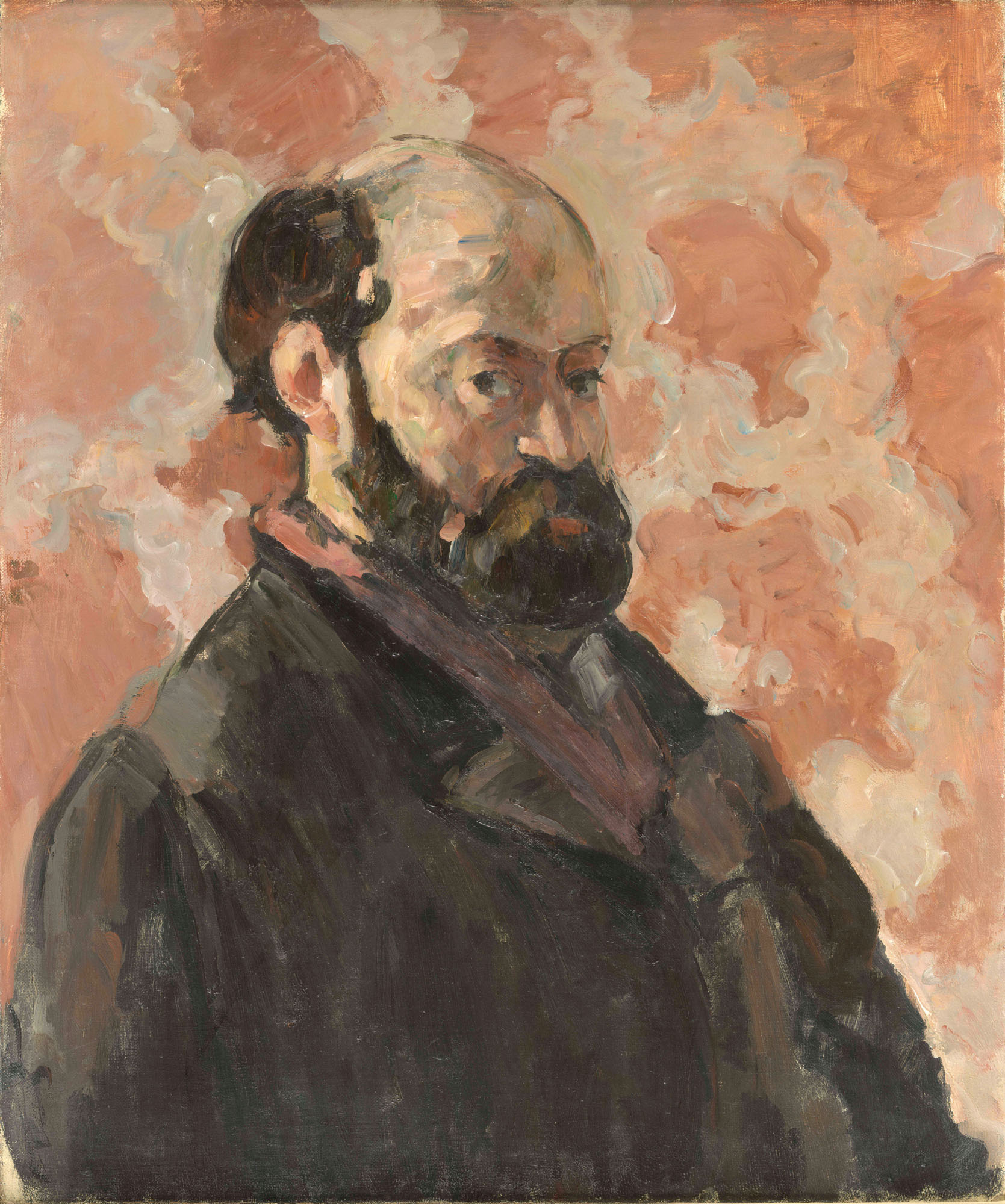

Not long after his death in 1906, Cézanne was already being hailed by a younger generation of artists and critics as a great innovator who had paved the way for Cubism, which seemed the perfect embodiment of his advice to ‘see in Nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone’. Yet anyone who had visited his studio in the 1860s, when he was in his mid twenties, would have been astonished to learn that he would come to be regarded as the grandfather of a radical-art movement that appeared to dispense with references to Nature altogether. On his easel, they would have seen technically crude portraits of family and friends and dramatic figure compositions captured in thick swirls of black and brown paint that gave little hint of the carefully constructed and colourful canvases of his maturity.

Cézanne — who is the subject of this season's EY Exhibition at the Tate Modern until March 12, 2023 — did not have the precocious virtuosity of many great artists, but he had stubbornness and single-mindedness. His determined struggle to capture his own sensations on canvas — what later generations would praise as his ‘anxiety’ or ‘unease’ — was what led to his greatness. Born into a prosperous family in Aix-en-Provence in 1839, he started on the career path his father had set out for him and began training to be a lawyer. Yet it was soon evident that he had no appetite for the legal profession and, at the age of 22, encouraged by his friend Emile Zola, he left for Paris to pursue his artistic ambitions and enrolled in an art school. It was not an easy transition: he was never entirely at ease in the capital and soon returned home. For the rest of his life, he would oscillate between Provence, Paris and the Île de France, typically spending part of the year in each place.

Cézanne hoped to achieve fame and respect among his fellow artists and the art market, but the path to recognition was tortuous. The jury of the annual Paris Salon exhibitions continuously rejected his paintings when he submitted them between the ages of 25 and 47, after which he stopped sending them altogether. It was lucky that he could rely on a modest allowance from his father to keep him afloat, as he was 35 before he sold a single painting to anyone other than friends and supporters. The allowance had some drawbacks, however: Cézanne felt obliged to hide the existence of his mistress, Hortense, and their son, Paul, from his father for years, for fear of incurring his disapproval and the end of the paternal subsidy.

Cézanne may not have found acceptance among the Paris art establishment, but his idiosyncratic personality made a profound impression in avant-garde artistic circles. He clung tenaciously to his Provençal identity, deliberately cultivating an image of himself as an ill-mannered rustic. On one occasion, he turned up at the Café Guerbois, the favourite drinking spot of Manet and other artists, hitched up his trousers, tied a red sash around his waist and announced: ‘I won’t offer you my hand, Monsieur Manet. I haven’t washed in eight days.’

That apparent uncouthness remained a constant feature. As late as 1894, when the American painter Matilda Lewis met Cézanne at Monet’s house in Giverny, she remarked that ‘he looked like a cut-throat with large red eyeballs standing out from his head in a most ferocious manner, a rather fierce-looking pointed beard, quite grey, and an excited way of talking that positively made the dishes rattle’. Yet she realised that underneath the gruffness was a man of great sensitivity: ‘I found later that I had misjudged his appearance, for far from being fierce or a cut-throat, he has the gentlest nature possible…’

The leading Impressionists — Degas, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Gauguin — were intrigued by the originality of his work, as well as his unusual personality. In 1873, Cézanne, Hortense and Paul settled in the Parisian suburb of Auvers, within walking distance of Pissarro’s home in the neighbouring village of Pontoise. A kindly father figure, Pissarro was quick to realise Cézanne’s unique qualities as an artist and encouraged him to paint in the open air, in front of Nature. The two spent days and weeks working alongside each other. The dark, muddy colours and violent contrasts of Cézanne’s earlier canvases were replaced with lighter tones and brighter colours.

Turbulent figure scenes gave way to carefully considered landscapes. Rather than trowelling on paint with a palette knife, Cézanne developed a new method of applying it in parallel strokes of the paintbrush. Pissarro’s depiction of rural life often included images of people at work, but Cézanne’s painted landscapes were almost depopulated and purged of superfluous anecdotal detail. He gradually began to abandon the conventional method of creating perspective in a picture by spacing out planes towards the horizon with converging straight lines and carefully graded colour. Instead, he flattened and compressed space; background and foreground began to merge in patches of brilliant colour.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This obsession with new methods of constructing pictorial space was very different from the Impressionists’ concern with fleeting effects. ‘Pissarro had an enormous influence on me,’ Cézanne later remarked. ‘But I wanted to make of Impressionism something solid and enduring like the art of museums.’ The same quest for solidity and the same disruption of perspective spilled over into his still lifes and portraits, too.

In his Still Life with Plaster Cupid, a small 17th-century sculpture is surrounded by fruit and vegetables and canvases seem to be propped up against a wall, but it is difficult to know where exactly everything is placed. The green apple, apparently in the background, looks surprisingly large and there seems to be a blurring of distinction between the fruit and vegetables on the table and the painted ones enveloped in blue drapery on the canvas.

Cézanne once claimed that he would astonish Paris with an apple and in his Basket of Apples does indeed surprise. The brilliantly coloured pieces of fruit spill out onto a tablecloth that appears as solid as a hill, perched on a tabletop that does not make sense as a structure, but looks as if it is tilted upwards. He was not aiming for an exact imitation of Nature, but to re-create the sensation he felt in front of objects, to give some sense of how we look at scenes from multiple viewpoints simultaneously.

Following his father’s death in 1886, an inheritance alleviated any financial worries Cézanne may have had. He began to spend more time in Aix-en-Provence, initially at the family home, Jas de Bouffan. Hortense was reluctant to live permanently in Provence and she and their son spent most of their time in Paris. By this time, Cézanne was meeting with some professional and critical success and attracting the admiration of some younger artists, but that did nothing to allay his suspicions of the art world. Relishing his increasing solitude and remoteness from the bustle of the capital, he could focus on the landscape that meant most to him. He walked for miles through the countryside, obsessively painting and drawing Montagne Saint-Victoire from various vantage points, as well as local landmarks such as the neo-Gothic manor house, the Château Noir and the Bibémus quarry.

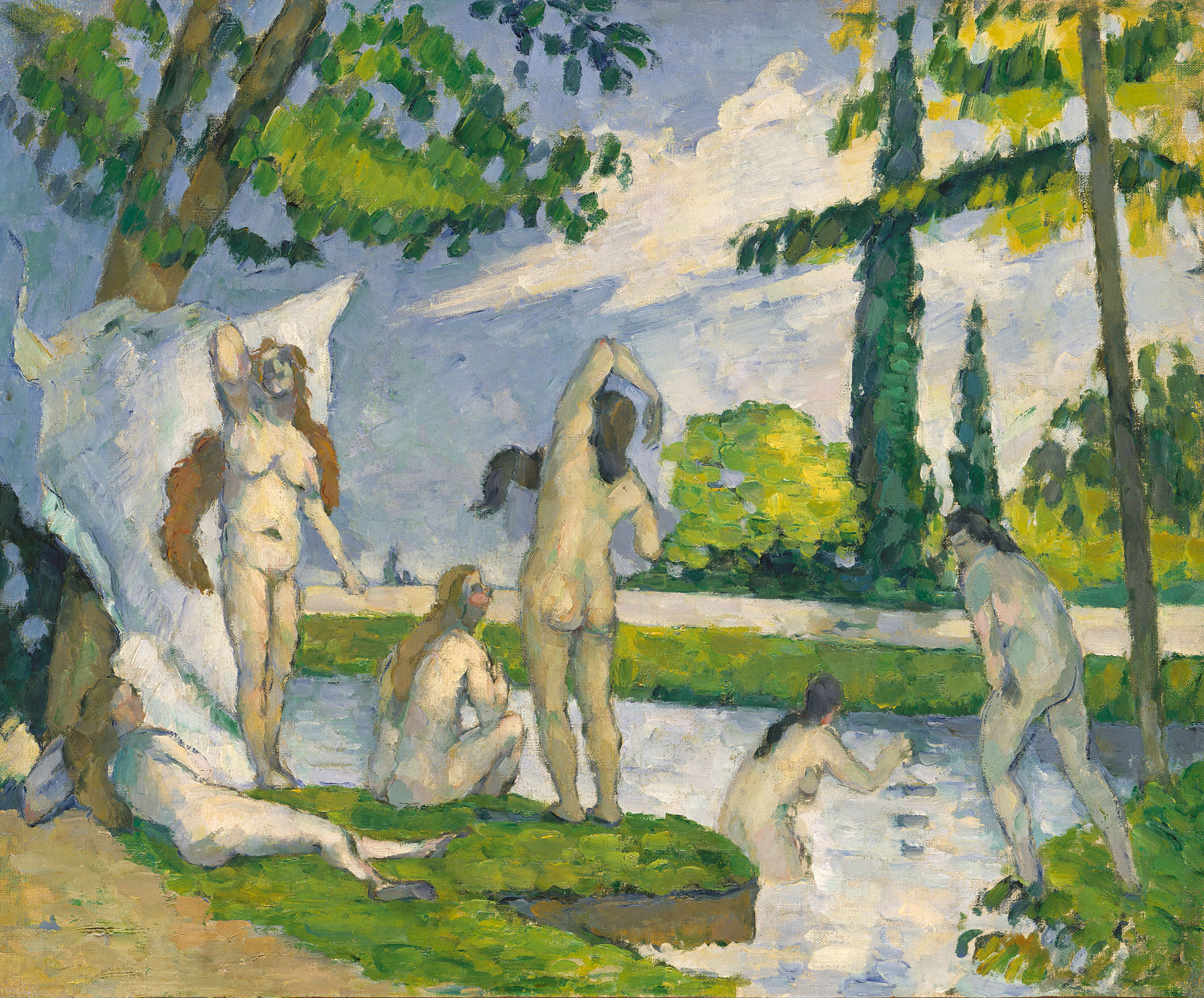

He persuaded the workers and craftsmen of Aix to pose for him, including the gardener Vallier, who complained that the sittings were so long he didn’t have time for gardening. Local people also posed for a remarkable series of five paintings of card players focusing on their game with intense concentration. In some ways, the humble subject matter was the antithesis of the other theme that preoccupied him during his final years: the Classical subject of bathers in a landscape, which he painted on a monumental scale. As in all of Cézanne’s figure paintings, the anatomy in these pictures is distorted and unrealistic, but accuracy was not necessarily what Cézanne was striving for. The women are part of the architecture of the landscape they inhabit, their bodies as solid as the rocks and trees that surround them. These last paintings can be seen as Cézanne’s final celebration of Nature and our union with it.

‘The EY Exhibition Cézanne’ is at Tate Modern, London SE1, until March 12, 2023 (www.tate.org.uk)