Paris 1924, when sport came headfirst into an intoxicating mix of art, fashion and desire

When the Olympics opened in Paris in 1924, the French capital was already gripped by a ferocious blend of art, literature, cinema, fashion and a wild desire to dance. Sport merged into this culture to become the pinnacle of an extraordinary time, as Mary Miers reveals.

One morning in 1919, Fernand Léger, the avant-garde painter of modern Paris, was sitting in a Montparnasse café when Jeanne-Augustine Lohy pedalled past in full bridal dress with billowing veil. Her bicycle was a wedding present and she’d been unable to resist a spin, but she’d taken the wrong route and was now late for her nuptials. The handsome artist stepped in and assured her all was not lost. ‘Before long,’ recounts Mary McAuliffe in her book When Paris Sizzled, ‘Lohy became Madame Léger.’

The surreal vignette encapsulates the spirit of Paris on the brink of les années folles, the decade that would see the city’s resurgence as European capital of modernity. Léger was fascinated by machines, as well as by film and graphic design. After returning from the Western Front, he developed his own Futurist version of Cubism that evoked the speed and cacophony of the industrialised metropolis in boldly coloured paintings composed of geometric and cylindrical shapes and dislocated figures.

A key subject was the Eiffel Tower, looming over Paris on its great splayed legs. Erected as a temporary monument for the Universal Exposition in 1889, it was still the predominant emblem of French design and technology, as the war-torn city underwent reconstruction. Léger’s friend and fellow Cubist Robert Delaunay painted it some 50 times; it featured in Jean Cocteau’s nonsensical ballet Les mariés de la tour Eiffel and was transformed into a spectacular billboard during the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, when the name Citroën was illuminated down its three sides in 250,000 neon lights. Nothing encapsulated better the dazzling ingenuity of modern Paris, the so-called City of Light.

Writing to the painter André Mare, Léger noted that Parisians were ‘gripped by a wild desire to dance, let off steam, scream, at long last stand upright, shout, scream and squander’. In this intoxicating climate, women, although still unable to vote, expressed their independence through liberated behaviour and styles of dress, the anti- art Dada movement gave way to Surrealism and, to quote from Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises, Paris became ‘the town the most sportif in the world’.

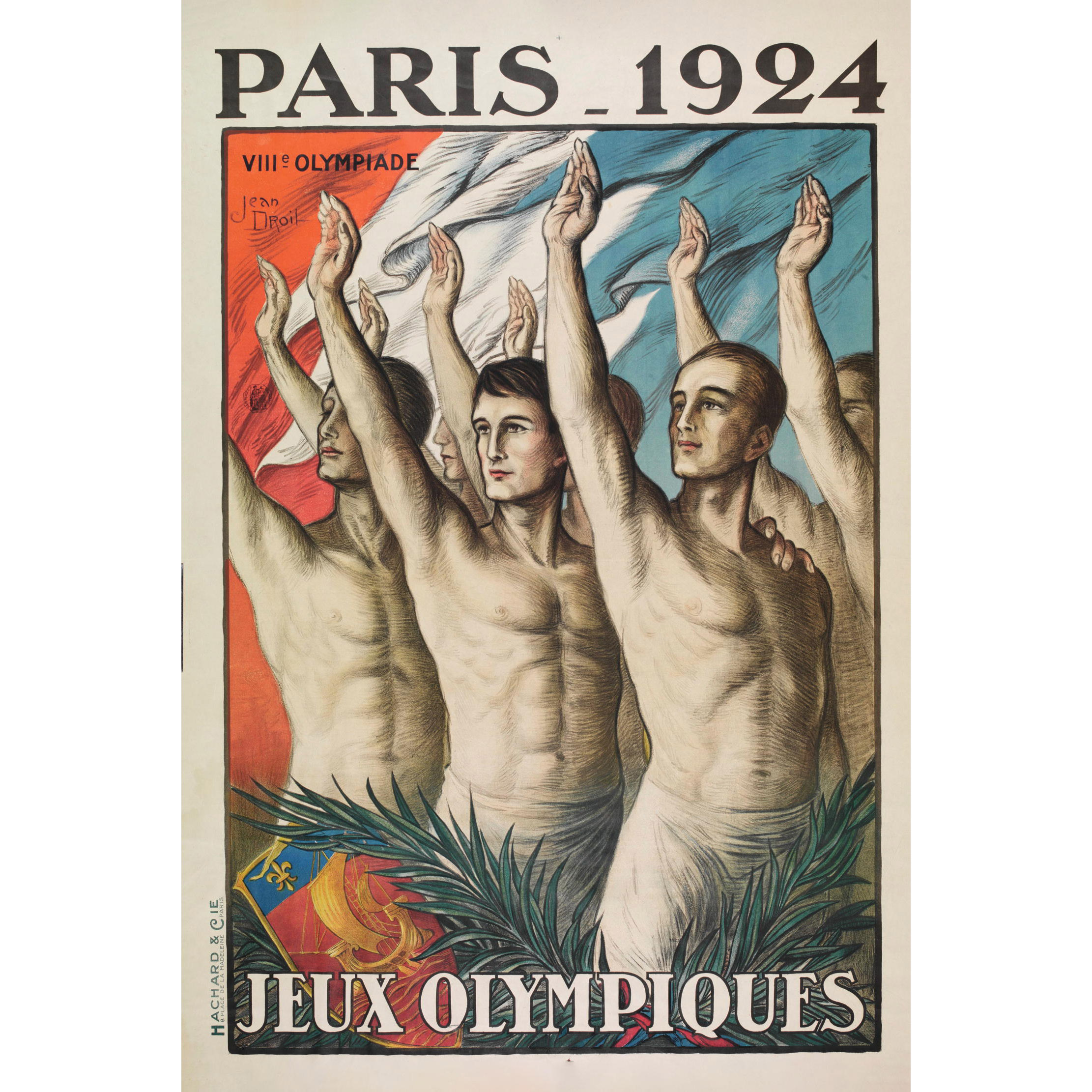

‘Faster, higher, stronger’ was the motto emblazoned across the city in 1924, when the Olympics brought an influx of athletes performing astonishing feats. The Games were the culminating spectacle of an extraordinary year, in which Paris saw the launches of André Breton’s Surrealist manifesto; of Le Corbusier’s Urbanism, setting out his ideas for the city of the future; Citroën’s B10, the first steel motorcar; Les Parfums Chanel; Marc Chagall’s first Paris retrospective; André Gide’s dialogues on homosexuality and the nightclub Bal Nègre. Also drawing crowds were innovative films, such as Émile Keppens’s Paris la nuit, Serge Nadejdine’s Le Chiffonnier de Paris and René Hervil’s Paris, as well as the first performance of the ballet Le Train Bleu, featuring choreography by Bronislava Nijinska, a libretto by Cocteau, costumes by Coco Chanel and a curtain painted by Pablo Picasso. In a Montmartre music hall, Comte Étienne de Beaumont launched his Soirées de Paris, engaging the cream of Parisian writers, musicians, dancers and painters to collaborate on productions, and in his dark room the photographer Man Ray developed Le Violon d’Ingres, superimposing a violin onto his mistress’s bare backside.

The bicycle was central to the image of La France Sportive, bicycle-racing having emerged in the 1890s as the country’s leading professional sport. Under the influence of the educational reformer Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics (first held in Athens in 1896), other sports had become popular in France — some, such as rowing and football, imported from Britain, together with significant elements of de Coubertin’s vision for fostering ‘moral and social strength’, patriotism and international links through competitive games.

The 1924 Olympics had an unprecedented impact on cultural life, thanks to pioneering approaches to advertising and broadcasts using radio, film, graphics and electric light. Contestants such as the American swimmer/actor Johnny Weissmuller (who would later play Tarzan) and the Finnish runner Paavo Nurmi personified the Olympian ideal of strength and beauty at a time of growing interest in antiquity. Their sleek, muscular physiques influenced changing attitudes to health and fitness, as well as inspiring fashion, poetry and art. Paris-based Kostas Dimitriadis modelled a celebrated version of Myron’s 450BC Discus Thrower; Wäinö Aaltonen’s large-scale statue of Nurmi and Renée Sintenis’s smaller sporting bronzes introduced speed and a modern sensibility to the traditional representation of the athletic figure.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Sportswomen, notably Suzanne Lenglen (after whom the tennis player in Le Train Bleu was modelled) and Helen Wills, inspired the new ‘style sportive’ in women’s leisurewear. Rival couturiers Chanel and Jean Patou had revolutionised fashion with chic yet casual designs, raising hems, dropping waistlines and using simply cut, fluid fabrics to create a freedom of movement that reflected their wearers’ new lifestyles. By the mid 1920s, the emphasis was on geometric shapes and boyish, athletic figures, with headbands worn over Eton crops. When the flamboyant Elsa Schiaparelli opened her Paris boutique in 1927, she called it Pour le Sport. Her striped swim ensemble featured in Vogue the following year.

Sport was also reflected in the new medium of cinematography, which flourished in Paris in the 1920s. Jean de Rovéra made three films about the Olympics and the sporting theme would be adopted in other fictional, animation and documentary films. One device used with particular effect was slow motion, memorably revived in the 1981 film Chariots of Fire.

As Europe recovered from the chaos of war, many artists and designers returned to neo-Classicism. Unable to make it as a painter in Paris, Corbusier launched his L’Esprit nouveau, promoting ‘artistic balance and mathematical order’ through clean lines and geometric forms. He started to apply his Purist functionalism to the design of standardised family houses and his architectural career took off. Picasso’s return to a more figurative style is exemplified by his huge Three Graces panel of 1923, painted to decorate a fairytale extravaganza for which he also designed the costumes.

De Coubertin’s vision for a great urban space harmonising sport, spectacle and design was realised in Bévière’s Piscine des Tourelles, built for the Olympics with eight stairways and terracing for 10,000 spectators. The Classical monumentality of this aquatic arena celebrated Art Deco, the style that would dominate the Paris Exposition the following year.

Art intersected with sport through contest, too. Initiated by de Coubertin, the Olympic Arts Competition took over the Grand Palais and the Theatre des Champs-Elysees and was judged by leading figures in the different fields, John Singer Sargent, Edith Wharton and Béla Bartók being on the list. Few of the Parisian avant-garde entered, however, and the medal winners were relatively conventional.

By 1924, the population of Paris had swelled to above three million, including more than 30,000 Americans, twice that many British and a vibrant mix of émigré intellectuals and artists from Russia and Eastern Europe. Jewish painters Sonia Delaunay, Chaïm Soutine and Chagall rubbed shoulders with writers Langston Hughes and Jessie Fauset of the Harlem Renaissance. In 1925, African-American dancer Josephine Baker launched herself on Paris with the music-hall Revue nègre and began her reign as Queen of the Night.

‘Everything is gay and moving… everyone is on the streets — it is a big Greenwich Village, but with wine and beer everywhere,’ Man Ray wrote to his brother after arriving from New York in 1921. Many of his compatriots came to escape what the writer Malcolm Cowley described as ‘the triumphant causes in America’ — ‘prohibition, puritanism, philistinism and salesmanship’. One could add racism to the list — although some imported it, objecting to the lack of segregation in nightclubs.

Woody Allen’s magical film Midnight in Paris introduces us to the most famous group of Americans in the city — the ‘lost generation’ of writers and poets who came in search of a publisher, entertainment and distraction. Hemingway and F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, bored and self-indulgent, socialised with T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Djuna Barnes, James Joyce and Sylvia Beach at the literary salons of fellow American Gertrude Stein. Aimlessly, they moved from party to party, mingling with Picasso, his mistress, Cocteau, Salvador Dalí, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray to the songs of Baker and Cole Porter. The epicentre of their world was Montparnasse, the gritty quarter of the Left Bank where impoverished artists and writers could get cheap lodgings and food, hear Man Ray’s mistress Kiki singing bawdy songs at the Jockey Club and dance to jazz and ragtime at Le Bal Blomet. ‘We generally spent every night in cafés in Montparnasse. If I were to add up the hours I have whiled away at the Café du Dôme, La Cupole, the Select, the Dingo and the Deux Magots (in the Saint-Germain quarter) and the Boeuf sur le Toit, I am sure it would amount to years,’ revealed Peggy Guggenheim in her memoir.

As the wealthy colonised bohemian haunts, ordering cocktails at cafés newly redecorated with mirrored interiors, the old crowd began to disperse. Paris ‘had grown suffocating,’ lamented Fitzgerald in 1928. ‘With each new shipment of Americans spewed up by the boom the quality fell off, until towards the end there was something sinister about the crazy boatloads.’ There was something sinister, too, in the way sport was being appropriated by increasingly militant Fascist movements, such as Action Française. In 1928, Hemingway returned to the US with his new wife, yet, for all the disillusionment, the enchantment stayed with him. As he famously wrote in 1950: ‘If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a movable feast.’

Art of gold: 'Paris 1924: Sport, Art and the Body' at the Fitzwilliam

A new exhibition explores the intersection between sport and art in the context of 1924, when the cosmopolitan capital of modernity embraced the classical inheritance of the Olympics.

Marking the centenary of the Games’s return to Paris, the show explores the visual impact and how this reflected changing attitudes to sporting achievement and celebrity, body image and identity, nationalism, class, race and gender at a pivotal moment in history that seems increasingly relevant today.

‘Paris 1924: Sport, Art and the Body’ is at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, until November 3. See www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk.

Credit: Ekaterina Pokrovsky

The Country Life guide to Paris, France: Where to go, what to see, where to stay and what to eat

Paris is always a good idea, so here’s our guide to what to do, where to stay and what to

The Country Life guide to St Tropez: Where to go, what to see, where to stay and what to eat

St Tropez — or Saint-Tropez — is one of the best know holiday destinations in the world and has, over

The Country Life guide to Capri, Italy: Where to go, what to see, where to stay and what to eat

First popularised as a holiday destination by the Roman Republic, the Italian island of Capri shows no signs of losing

Credit: Le Meurice

Le Meurice Paris hotel review: Illuminating art in the city of light

What are the ingredients of an unforgettable trip to Paris? An overnight stay at The Dorchester on Park Lane, before

Mary Miers is a hugely experienced writer on art and architecture, and a former Fine Arts Editor of Country Life. Mary joined the team after running Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. She lived in 15 different homes across several countries while she was growing up, and for a while commuted to London from Scotland each week. She is also the author of seven books.