One of the cleverest pictures ever made, and how it was inspired by one of the cleverest art books ever written

The rules of perspective in art were poorly understood until an 18th century draughtsman made them simple. Carla Passino tells the story of Joshua Kirby.

Perspective much preoccupied 18th-century British fine and decorative artists. William Hogarth saw it as adding beauty ‘by seemingly varying otherwise unvaried forms’ and Thomas Chippendale noted that ‘without… some knowledge of the rules of Perspective, the Cabinet-maker cannot make the designs of his work intelligible’.

Mastering it, however, could be challenging. A guide came in the form of mathematician Brook Taylor’s 1715 treatise, but his writing was at best obscure. It fell to topographical draughtsman Joshua Kirby (1716–74) to distil Taylor’s work into manageable instructions. His Dr Brook Taylor’s Method of Perspective Made Easy, published in 1754.

The book came with a frontispiece by Hogarth, which you can see at the top of this page, which is surely one of the cleverest and funniest images ever created: two centuries before M.C. Escher was making water run uphill, Hogarth’s drawing — featuring what he called ‘a whimsical collection of the most absurd solecisms against the rules of perspective’ — is a miniature marvel. As indeed was the book it appeared in, for Kirby’s tome proved to be a game-changer for artists — not to mention for the writer himself.

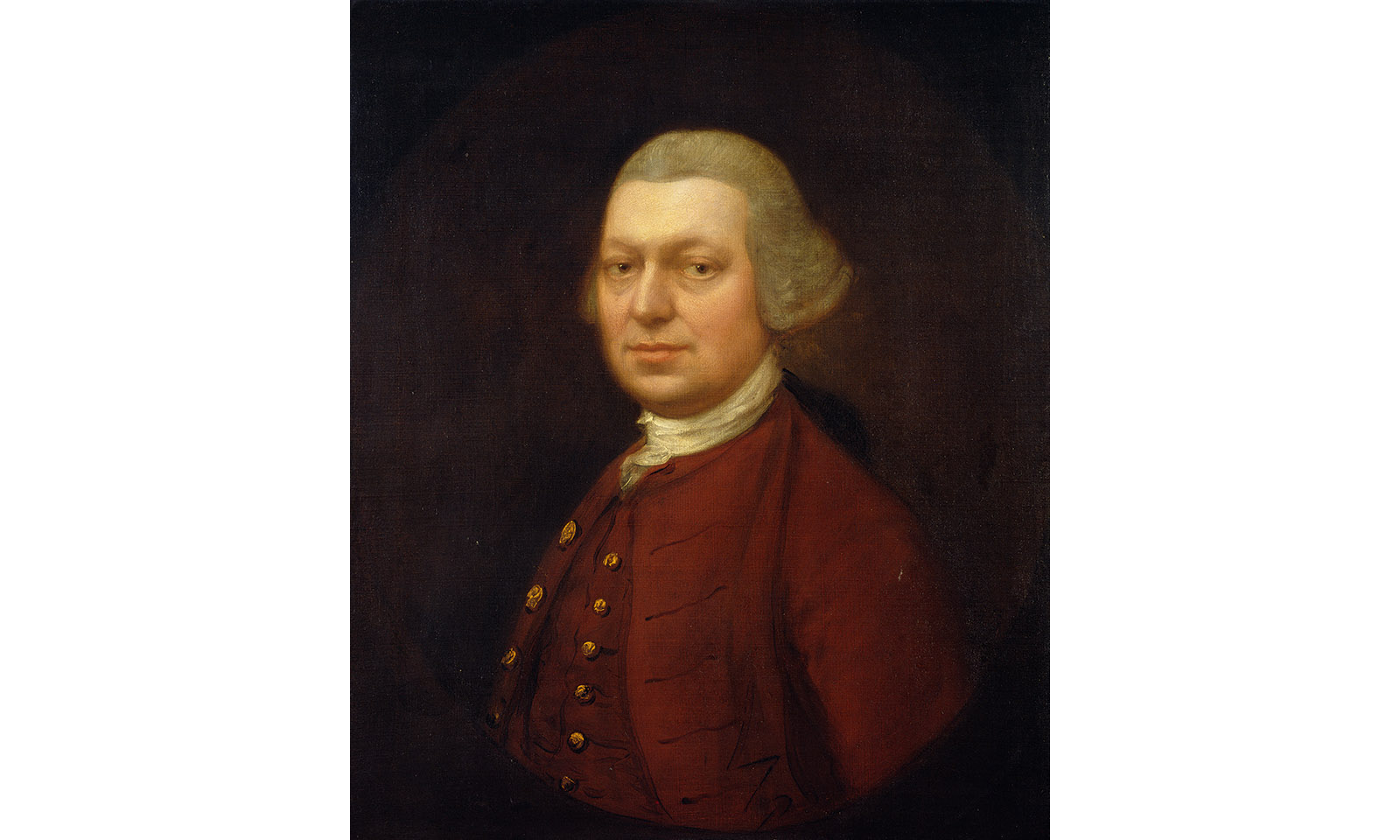

Born at Parham, Suffolk, Kirby had begun his career as a painter of houses and carriages, but later took up landscapes (with some encouragement from Gainsborough, who painted him).

After his book was published to great acclaim, he taught perspective to the future George III, who upon his accession appointed him Clerk of the Works at Kew. Despite building his entire career on perspective, Kirby firmly believed in the artist’s right ‘to be guided by his own Judgement’, and was criticised for this by those, such as painter Joseph Highmore, who maintained no one should ‘take any Liberties whatsoever’.

Asking Hogarth in 1753 to append some thoughts to his forthcoming book, Kirby didn’t mince words about his detractors: ‘If the little witlings despise the study of perspective, I’ll give ’em a thrust with my frontispiece which they cannot parry; and if there be any that are too tenacious of mathematical rules, I’ll give them a cross-buttock… and crush them into as ill-shaped figures as those they would draw by adhering too strictly to the rules of perspective.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.