Nikolai Astrup: Painting Norway

Nikolai Astrup at Dulwich Picture Gallery makes for an atmospheric show

If you haven’t heard of the Norwegian artist Nikolai Astrup (1880–1928), it’s not surprising, as there is not a single work by him in any UK museum or gallery and virtually none outside his native country. However, in Norway itself, Astrup is regarded as something of a hero, his works treasured as icons of national identity. Astrup launched his artistic career just as Norway gained its constitutional independence from Sweden.

A tide of nationalist sentiment and a growing awareness of the country’s regional cultures were widely reflected in art, literature and music. Although he travelled abroad in search of training and artistic knowledge, he always returned to western Norway, where he had grown up. In the relatively confined area around Lake Jølster, he found all the subject matter he would ever need.

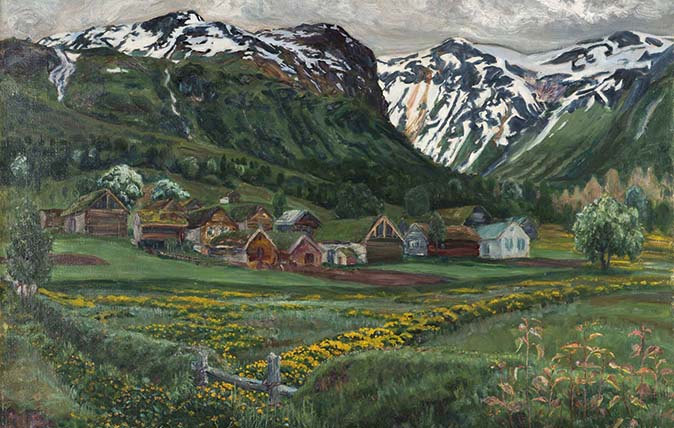

The 90 works hanging on the walls of Dulwich Picture Gallery reveal a very specific landscape of meadow and pasture enclosed by mountains and lapped by the waters of the lake. It’s not the place of romantic threatening peaks and thundering seas depicted by an earlier generation of Norwegian artists such as Peder Balke (whose works were shown at the National Gallery last year), but possesses an altogether quieter poetry.

Astrup’s enchanted land is suffused with recollection and myth and tempered by human presence. Many of the paintings depict views or events he had seen as a sickly child staring out of the windows of the damp parsonage where his family lived. One of the things that make them so distinctive is their treatment of light: Astrup maintained that the light in western Norway was so pure that distant objects were seen as crisply as near ones. Unlike the Impressionists, he wasn’t interested in blurred horizons or foggy atmospheric effects.

He was, however, fascinated by the way that the light at different times of day and in different seasons changes the mood of a landscape. He observed the perpetual dusk of midsummer nights; he noted how the summer sun brought colours into sharp relief; how moonlight was reflected on the lake and how it gave the snow on the mountains a pink glow; how clouds cast a grey pall over buildings; and how the sun after rain intensified the green of the fields.

There is an apparent naïvety in Astrup’s work it is interesting that one of his favourite artists was the French naïve painter Henri ‘Le Douanier’ Rousseau but Astrup was far from naïve. He kept abreast of the latest developments in European painting and shared the then-current obsession with Japanese prints. Some of his views look as if they are viewed through a Japanese lens, particularly the woodcuts.

In fact, his prints are highly experimental. He saw them not as a cheap way of producing multiple images, but as individual works of art like his paintings. No two are identical, as he usually added dabs of paint to each one and, when he reused woodblocks of the same composition, he varied the colours to create radically different effects.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In his thirties, Astrup acquired a smallholding at Sandalstrand on Lake Jølster, on the opposite shore to his childhood home. It became his greatest project and he proceeded to build several small log houses there, filling the garden with his favourite plants and vegetables to feed his growing family. Like the Swedish artist Carl Larsson, Astrup transformed his home and garden into a complete environment that was not only a comfortable refuge, but also a subject for art.

He recorded its daily rituals in paint: the family tending the garden, picking rhubarb to make into wine and milling about inside their home, which was decorated with textiles designed by his wife.

The artist also saw elemental pagan forces at work in the landscape. He painted trees that resemble trolls, grain drying on poles that look like ghostly figures marching across fields and, the most overtly pagan expression of them all, the midsummer celebrations. Every year on June 23, bonfires were lit in the countryside and couples flirted and danced with riotous abandon, echoing a primitive fertility ritual.

When Astrup was a boy, his Lutheran pastor father had forbidden him from joining in the festivities, but his fascination with them never went away. They crop up in a number of paintings, but they are always seen from a distance, from the perspective of a perpetually banned outsider.

These are works of memory and mood. ‘A painting should contain more than just decorative colour,’ declared Astrup, ‘it should depict human moods such moods that people who do not have the trained eye of a painter can also see and feel when they walk in nature.’

‘Nikolai Astrup: Painting Norway’ is at Dulwich Picture Gallery SE21 until May 15 (020–8693 5254; www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk)

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passions

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passionsVincent Zanardi reveals the present from his grandfather that he'd never sell and his most memorable meal.

By Rosie Paterson

-

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabinQatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin has been setting the standard for Business Class travel since it was introduced in 2017.

By Rosie Paterson