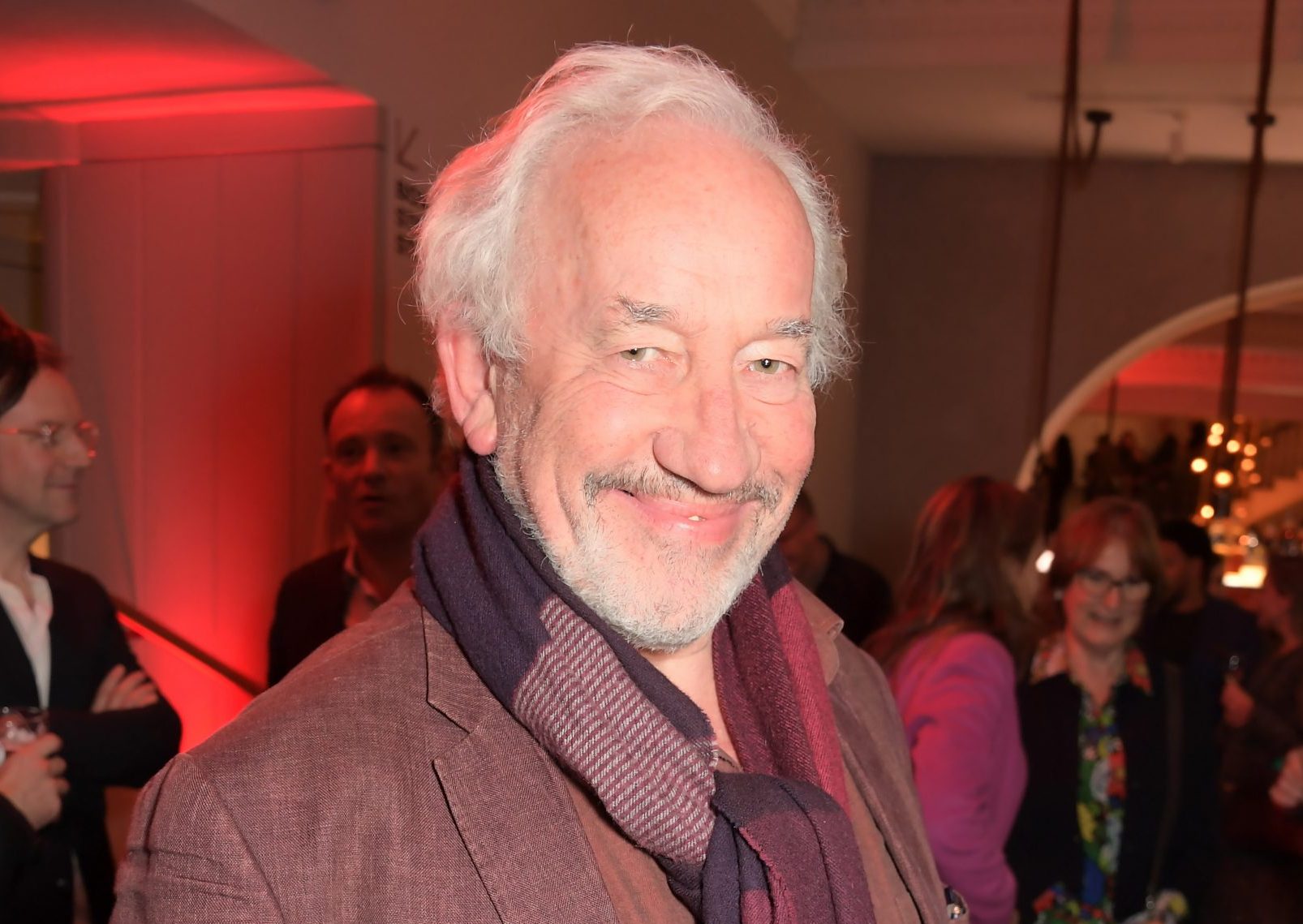

My Favourite Painting: Simon Callow

Actor, director, musician and bona fide national treasure Simon Callow chooses a haunting portrait by an Italian master.

Simon Callow on why he chose Portrait of a Young Man with a Book by Bronzino

'I have been haunted by Bronzino’s work since my adolescence, above all by the portraits, of which this, of an unknown young man, is among the very finest. They all have something in common, these portraits, which is, above all, in the relationship of the subject to the viewer — or, perhaps, the painter.

'These aristocrats make no concessions, no attempt to charm. But this haughtiness has a certain enigmatic quality to it. One longs to get inside their heads. This astonishingly self-contained young man almost defies you to get behind his mask. Perhaps it might be better titled Portrait of an Unknowable Young Man.'

Simon Callow is an actor, musician and theatre director. His latest book, in collaboration with photographer Derry Moore, is London’s Great Theatres.

John McEwen on Bronzino and Portrait of a Young Man with a Book

The Florentine Bronzino was the son of a butcher. At an early age, he became a pupil and adopted son of Jacopo Pontormo, one of the fathers of Mannerist painting, an elegant art of courtly style and wit. Through Pontormo, he gained the patronage of the Medici, becoming court painter to Cosimo I de Medici, Duke of Florence. He helped found Florence’s Academy of Art and Design and was noted for his art teaching. He also, less convincingly, wrote poetry.

This famous portrait in oil on wood (which was briefly part of Joseph Bonaparte’s booty when he usurped the Spanish crown in 1808) may indicate that its unnamed sitter is more than an educated person — perhaps the author of the book, even a poet with his latest work. As do three other portraits in this courtly vein, it pays acknowledgment to Michelangelo’s statue of Giuliano de Medici; such artistic reference was a Mannerist game. All these portraits have architectural backgrounds that, perversely, deny much information about the location.

This is particularly true of the background to this painting, in which the young man’s superior gaze, commanding stance and lavish clothes make him the very picture of youthful and privileged entitlement. Do the grotesque carved heads on the furniture subvert his assurance or merely suggest that it, too, can be a mask?

X-radiography and infrared reflectography show so many corrections —the architectural setting transformed, the book repositioned (originally, its spine faced the viewer with the covers splayed), the head re-drawn and so on — that it is speculated the portrait was begun, abandoned and only finished some years later.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025Tuesday's Quiz of the Day blows smoke, tells the time and more.

By Toby Keel

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon