My Favourite Painting: Ronel Lehmann

Ronel Lehmann chooses a classic Henry VIII portrait 'whose eyes followed me, watching my every move'.

Ronel Lehmann on Henry VIII (1560-80), after Hans Holbein

'I was fortunate to meet the Duke of Edinburgh at Buckingham Palace for a luncheon in aid of the Outward Bound Trust. He was running late from a meeting with First World War veterans and when he arrived I mentioned to him that it must have been a sad day. He immediately retorted ‘No, they are all bloody dead!’, causing much hilarity from the other guests.

'A few days later, he hosted a charity recital in aid of the Duke of Edinburgh Award at St James’s Palace. As I listened to the performance, I found my eyes drawn to a portrait of Henry VIII – taken from the lost Holbein original. Afterwards, as I wandered around the room, his eyes followed me, watching my every move. I have never forgotten the experience.'

Ronel Lehmann is the founder and CEO of Finito Education

John McEwen comments on Henry VIII

In 1537, Hans Holbein, Henry’s newly appointed Court painter, completed a life-size portrait of the King for a wall of the privy chamber at Whitehall Palace. It was a troublesome time in Henry’s reign. He had yet to father an heir, there was a continuing Catholic rebellion in the North and he was suffering from a jousting wound. He wanted Holbein’s portrait to remind his subjects and guests who was in charge.

The portrait was destroyed by fire in 1698, but part of the preparatory drawing survives, as well as a copy made for Charles II. Holbein’s image proved emblematic. A contemporary described it as ‘majestic… so lifelike that the spectator felt abashed, annihilated in its presence’. Henry was shown as a warrior, staring the viewer defiantly in the eye, standing with legs thrust apart. His bejewelled clothes were sumptuous, his codpiece aggressively exposed, his shoulders broadened by padding. He is in the forefront of a group surrounding a stone monument inscribed in his honour. To project his dynastic might his parents, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, stand above and behind with, opposite him, his latest wife, Jane Seymour. The dominance of his position and the inscription deem him mightier even than his father: ‘The son was born to a greater destiny. He it was who banished from the altars undeserving men and replaced them with men of worth… God’s teachings received their rightful reverence.’

This portrait is a late-16th-century derivation of the mighty mural. Painted on panel, it has been reduced in size and shows Henry as a firm, invincible ruler, rather than the banishing warrior of the original.

The Great Hall at Hampton Court, the building that 'brings the visitor closer to the world of Henry VIII than any other'

John Goodall looks at the remarkable history of Henry VIII's celebrated great hall at Hampton Court Palace.

Hampton Court's Baroque era reinvention: The transformation of the threshold of power

Hampton Court's association with Henry VIII takes the focus away from its Baroque elements, but they're worthy of attention argues

The ill-fated life of Henry IX, the king that Britain never had

James VI's eldest son was groomed for the English throne from boyhood. He never made it that far.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham Dockyards

‘It had the air of an ex-rental, and that’s putting it politely’: How an antique dealer transformed a run-down Georgian house in Chatham DockyardsAn antique dealer with an eye for colour has rescued an 18th-century house from years of neglect with the help of the team at Mylands.

By Arabella Youens

-

A home cinema, tasteful interiors and 65 acres of private parkland hidden in an unassuming lodge in Kent

A home cinema, tasteful interiors and 65 acres of private parkland hidden in an unassuming lodge in KentNorth Lodge near Tonbridge may seem relatively simple, but there is a lot more than what meets the eye.

By James Fisher

-

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite painting

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite paintingAlexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, chooses an Edwin Landseer classic.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

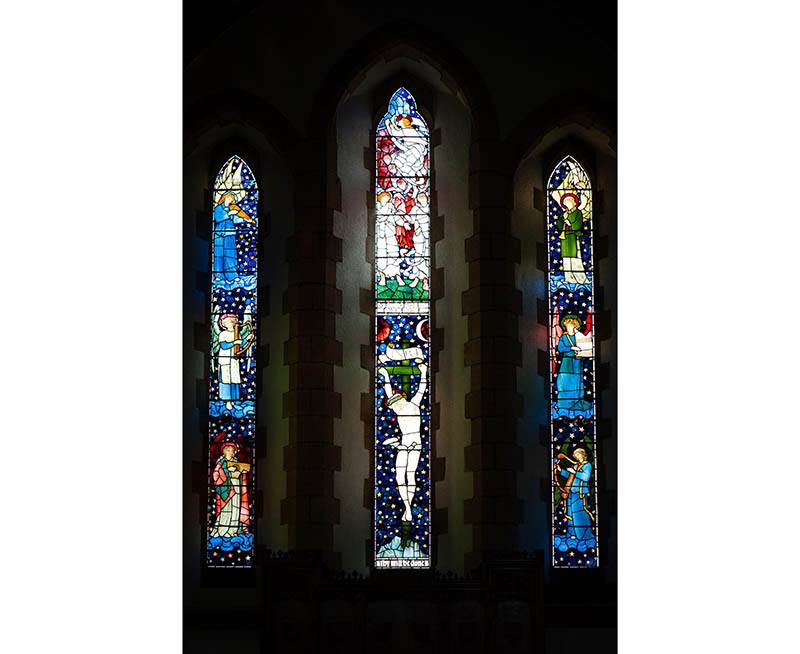

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in Britain

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in BritainThe painter Edward Burne-Jones turned from paint to glass for much of his career. James Hughes, director of the Victorian Society, chooses a glass masterpiece by Burne-Jones as his favourite 'painting'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subject

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subjectFor Country Life's My Favourite Painting slot, the writer Emily Howes chooses a work by a daring and challenging artist: Frank Auerbach.

By Toby Keel

-

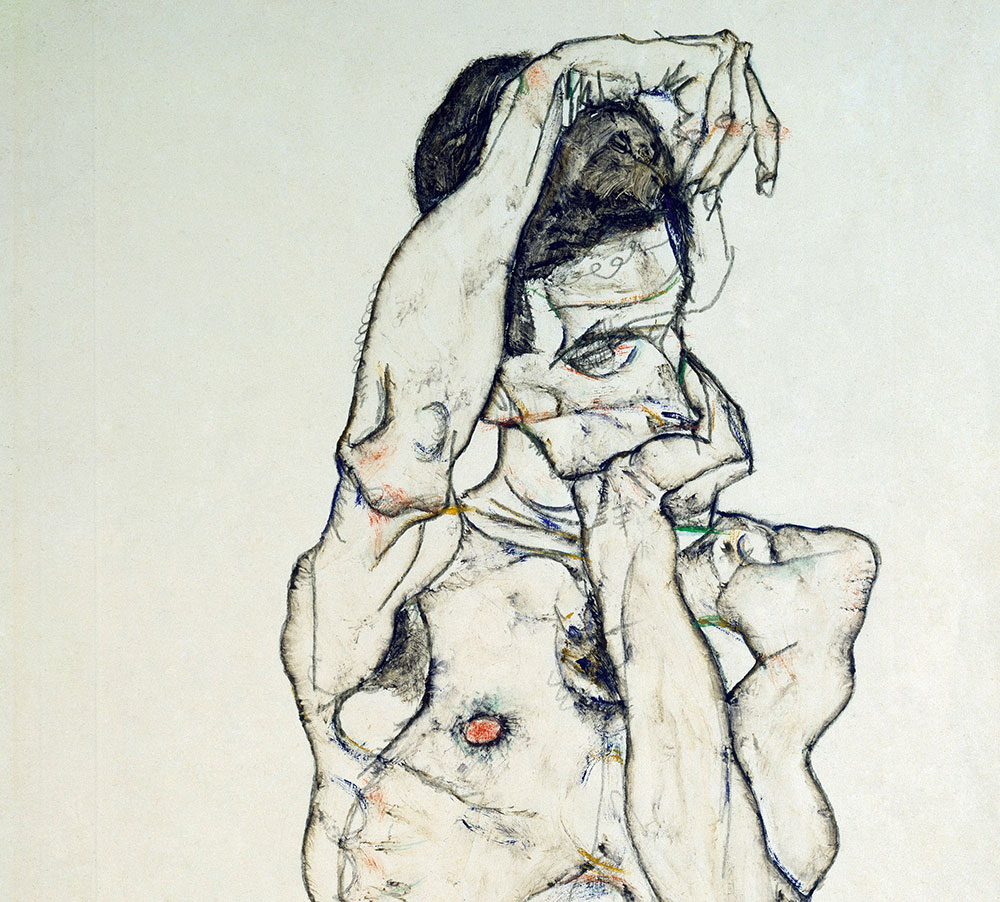

My Favourite Painting: Rob Houchen

My Favourite Painting: Rob HouchenThe actor Rob Houchen chooses a bold and challenging Egon Schiele work.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson'That's why this is my favourite painting. Because it invites you to imagine'

By Charlotte Mullins

-

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shock

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shockAs the National Gallery turns 200, the chair of its board of trustees, John Booth, chooses his favourite painting.

By Toby Keel

-

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearing

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearingChristopher Price of the Rare Breed Survival Trust on the bucolic beauty of The Magic Apple Tree by Samuel Palmer, which he nominates as his favourite painting.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon'Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .'

By Country Life