My favourite painting: Robert Macfarlane

Robert Macfarlane chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

Totes Meer, 1940–1, by Paul Nash (1889–1946), 40in by 60in, Tate Collection.

Robert Macfarlane says: 'A half moon, a grey-blue sky, the distant hint of a ridge and a shimmering silver sea of twisted fuselage and shot-up wing. Nash’s painting thrillingly chills me and, whenever I see it, my eye seeks out the sinister gliding back of that white owl in the top right corner, another kind of aerial hunter out for its prey. Totes Meer takes the English pastoral and torques it, trashes it. Along with Ravilious’s war paintings, Nash’s vision has shaped my own writing about the English landscape, helping me to see conflict as a condition of place, terrain as a function of wreckage and the natural as inextricable from the anthropic.'

Robert Macfarlane is the author of a number of books about landscape and the imagination, including The Wild Places, The Old Ways and, most recently, Landmarks. He is a Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

John McEwen comments on Totes Meer:

In the First World War, Paul Nash saw action on the Western Front as an officer before he was appointed an official war artist. In the Second World War, he was re-appointed to work on the Home Front. In 1941, he wrote to the Ministry of Information: ‘I should like [my official war] pictures to be used directly or indirectly as propaganda.’

Nash lived in Oxford, where Morris Motors had been partially assigned to aircraft production. Wrecked British and German planes were brought for recycling to the Metal Produce Recovery Unit at Cowley, a 100-acre field used as a dump. ‘The thing looked to me suddenly like a great inundating sea,’ the artist wrote. ‘You might feel—under certain influence—a moonlight night for instance—this is a vast tide moving across the field, the breakers rearing up and crashing on the plain.’ In keeping with its propagandist purpose, the resulting picture showed only German planes and he gave it a German title, Totes Meer (‘dead sea’), but it transcends propaganda and, therefore, time. He had provided a First World War masterpiece with his desolate Menin Road. Totes Meer is its Second World War equivalent.

The Imperial War Museum has a painting by Frances MacDonald of the Cowley dump. The wreckage is placed in the landscape. The season is suitably wintry and it has greater documentary interest, but it lacks Nash’s ‘very special talent for rendering certain poetical aspects... no other artist could’, as the art critic Roger Fry wrote to him in 1917.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The exhibition ‘Paul Nash’ will open at Tate Britain on October 26, 2016.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher

-

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite painting

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite paintingAlexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, chooses an Edwin Landseer classic.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

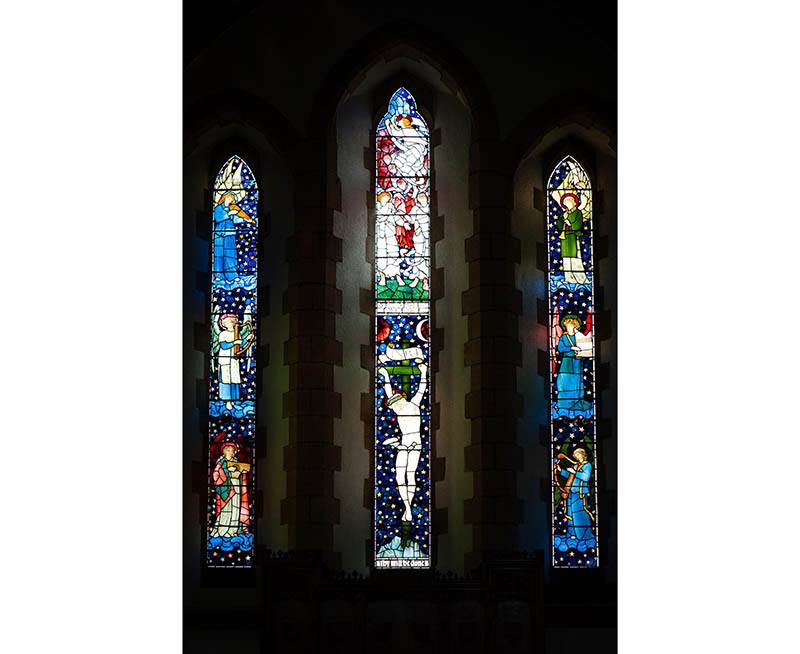

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in Britain

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in BritainThe painter Edward Burne-Jones turned from paint to glass for much of his career. James Hughes, director of the Victorian Society, chooses a glass masterpiece by Burne-Jones as his favourite 'painting'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subject

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subjectFor Country Life's My Favourite Painting slot, the writer Emily Howes chooses a work by a daring and challenging artist: Frank Auerbach.

By Toby Keel

-

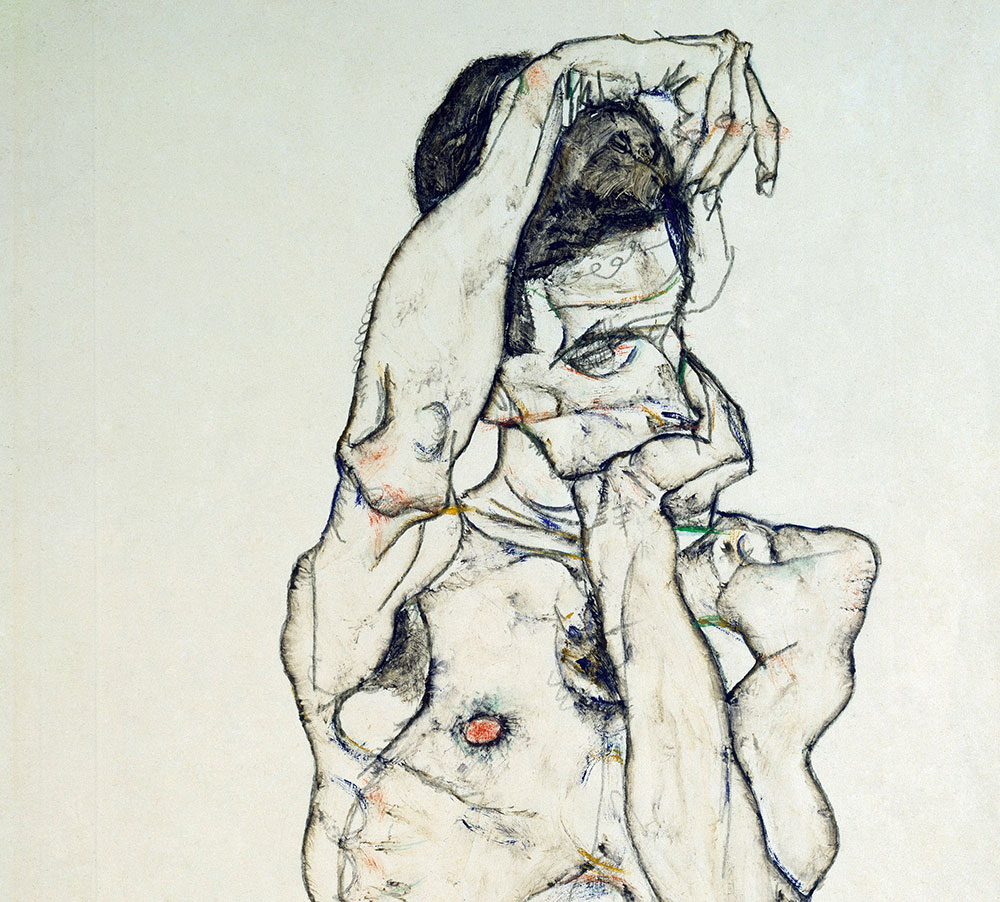

My Favourite Painting: Rob Houchen

My Favourite Painting: Rob HouchenThe actor Rob Houchen chooses a bold and challenging Egon Schiele work.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson'That's why this is my favourite painting. Because it invites you to imagine'

By Charlotte Mullins

-

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shock

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shockAs the National Gallery turns 200, the chair of its board of trustees, John Booth, chooses his favourite painting.

By Toby Keel

-

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearing

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearingChristopher Price of the Rare Breed Survival Trust on the bucolic beauty of The Magic Apple Tree by Samuel Palmer, which he nominates as his favourite painting.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon'Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .'

By Country Life