My Favourite Painting: Neil Mendoza

Lord Mendoza, provost of Oriel College, chooses 'The Painter and his Pug' by William Hogarth.

Neil Mendoza on The Painter and his Pug by William Hogarth

'It’s always such a treat to see “A Rake’s Progress” in its hidden place at the Sir John Soane’s Museum, WC2. But, of all Hogarth’s paintings, this self-portrait cuts straight through.

'Look at his stare, his dent of a scar, his Shakespeare and his dog, Trump. The trick of painting a portrait of a portrait. I wonder why he took 10 years to finish this picture.

'It’s hard to ignore his voice and personality looking straight out of the canvas, ready to take on a discussion or an argument and then lead you around 18th-century London.'

Lord Mendoza is provost of Oriel College, Oxford, commissioner for cultural recovery and renewal at DCMS and chair of The Landmark Trust and of the Illuminated River Foundation.

John McEwen on The Painter and his Pug

Approaching 50, William Hogarth re-worked an earlier self-portrait. He always loved pugs and probably included his favourite, Trump, for the first time, who then upstages him with all that his favoured status implied. He evokes the dog’s collar Hogarth’s contemporary, Alexander Pope, gave to Frederick, Prince of Wales, inscribed: ‘I am His Majesty’s dog at Kew, pray tell me, sir, whose dog are you?’

There was also a message for his fellow artists. Across the palette, an elegant line floated above a signed inscription of what it represented: ‘The LINE of BEAUTY and GRACE, W. J. 1745’. In opposition to the geometry of proportion, Hogarth advocated the beauty of this undulating ‘S’ line, key to sublime harmony, ‘admired and imitated’ by the ‘great Sculptors and painters’. Later, in 1753, he also wrote a book, The Analysis of Beauty, in which he described the reaction of artists to this first disclosure of the S: ‘No Egyptian hieroglyphic ever amused more than it did.’

The first version of this painting had advertised his artistic wares and success. There was an engraver’s tool, brushes sprouted from the thumb-hole of the palette and Hogarth wore a gentleman’s powdered wig and gold-buttoned clothes. In this 1745 version, he has a scholar’s soft hat and smock, which transforms into folds flowing out of the oval frame of the painting within the painting into the empyrean, the colour changing from earthly brown to commemorative grey. The books are by immortals: Shakespeare, Milton, Swift.

The portrait proclaims that Hogarth is no longer a professional on the make, but deserves recognition as a fellow maestro and an Englishman, hence down-to-earth Trump, worthy of any pantheon.

In Focus: The Hogarth masterpiece which shows that sometimes you need to 'listen' to a painting

A small exhibition at the Foundling Museum focuses on one painting — an image that inspires Huon Mallalieu to reflect

In Focus: The beauty of William Hogarth's 'Progress' Series, from his engraving skill to his story-telling gymnastics

Philippa Stockley revels in the humour, perspicacity and story-telling that radiate from Hogarth’s ‘Progress’ series.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The political cartoonist: 'Politicians hate how I depict them, but they'd hate it even more if I ignored them'

Peter Brookes, political cartoonist at The Times, is a savage commentator and the spiritual successor to the likes of Gillray

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson

-

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite painting

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite paintingAlexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, chooses an Edwin Landseer classic.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

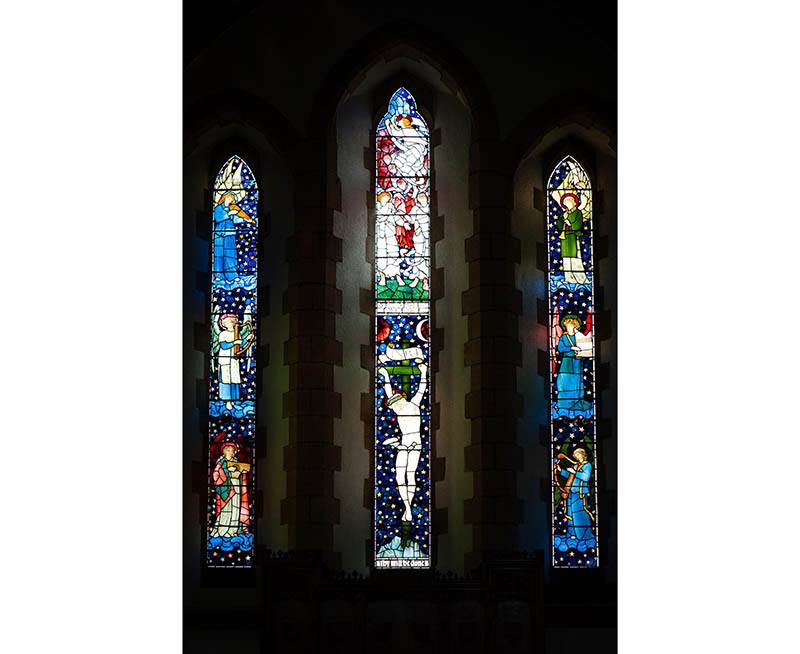

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in Britain

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in BritainThe painter Edward Burne-Jones turned from paint to glass for much of his career. James Hughes, director of the Victorian Society, chooses a glass masterpiece by Burne-Jones as his favourite 'painting'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

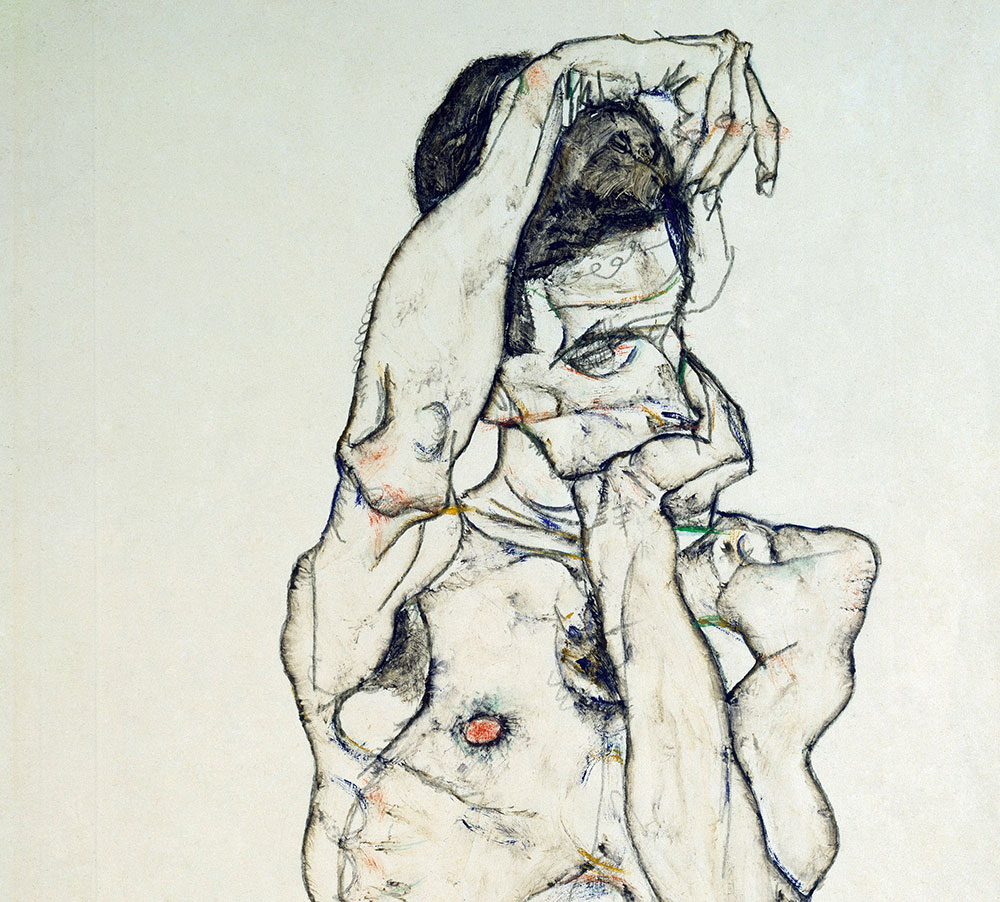

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subject

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subjectFor Country Life's My Favourite Painting slot, the writer Emily Howes chooses a work by a daring and challenging artist: Frank Auerbach.

By Toby Keel

-

My Favourite Painting: Rob Houchen

My Favourite Painting: Rob HouchenThe actor Rob Houchen chooses a bold and challenging Egon Schiele work.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson'That's why this is my favourite painting. Because it invites you to imagine'

By Charlotte Mullins

-

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shock

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shockAs the National Gallery turns 200, the chair of its board of trustees, John Booth, chooses his favourite painting.

By Toby Keel

-

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearing

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearingChristopher Price of the Rare Breed Survival Trust on the bucolic beauty of The Magic Apple Tree by Samuel Palmer, which he nominates as his favourite painting.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon'Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .'

By Country Life