My Favourite Painting: Deborah Swallow

Professor Deborah Swallow of the Courtauld Institute chooses an image by Oskar Kokoschka.

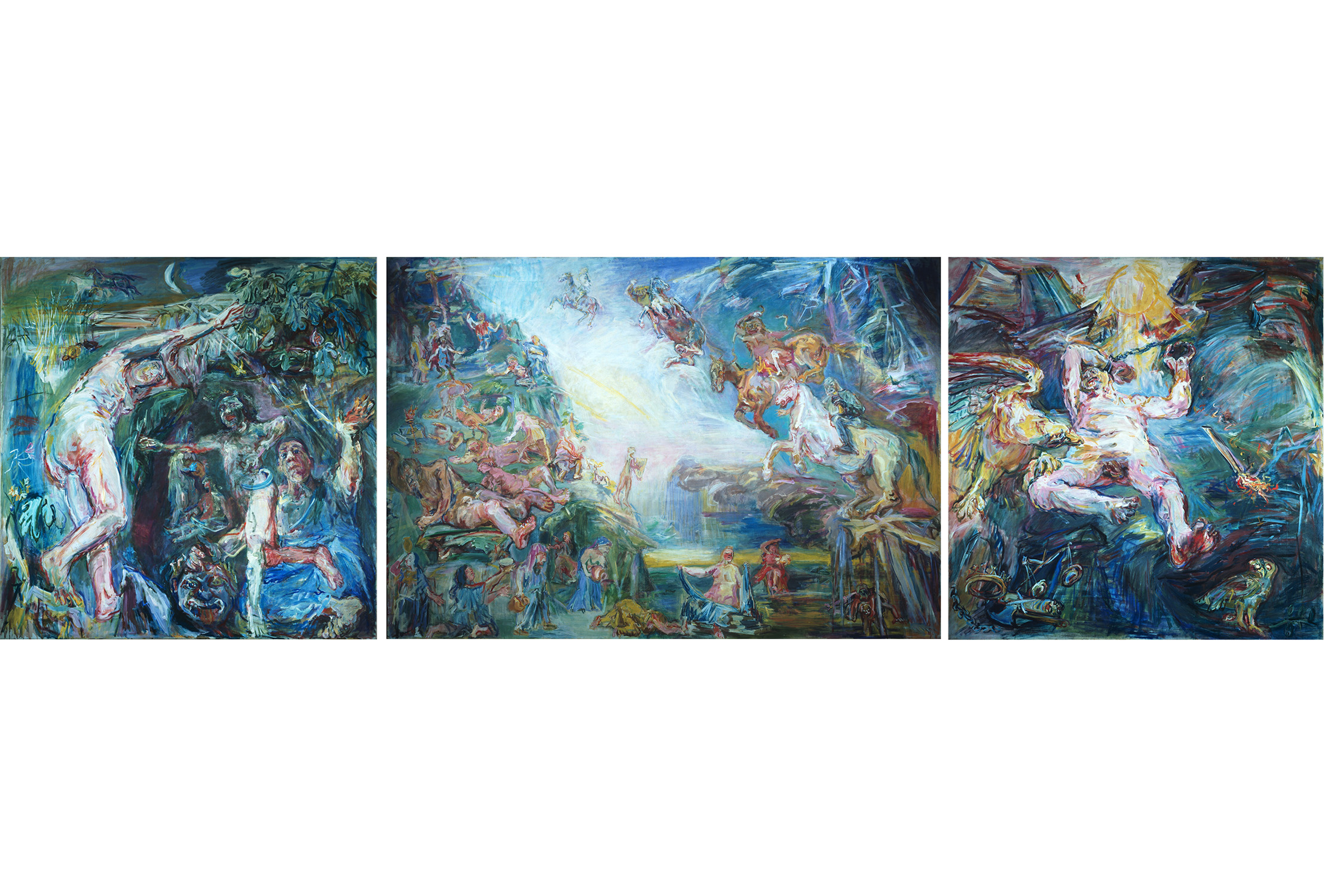

Deborah Swallow on Oskar Kokoschka’s Triptych

‘Oskar Kokoschka’s Prometheus has always fascinated me. Now, in a world turned upside down by a global pandemic, with daily reminders of environmental catastrophe, Kokoschka’s engagement with apocalypse, human pride and ambition and his representation of hope through the figure of Persephone speak ever more directly and powerfully to me.

‘Described as the most important Kokoschka in the UK, it was rarely seen in his lifetime and has been seen as rarely since. We will remedy this next year when The Courtauld Gallery re-opens its doors after a major renovation.’

Professoe Deborah Swallow is the Märit Rausing director of The Courtauld Institute of Art

John McEwen on Kokoschka and Triptych

The UK benefited greatly from the European diaspora between the wars, not least in the visual arts. One such refugee was the celebrated Viennese painter, poet, playwright and teacher Oskar Kokoschka. He did not settle, but stayed long enough to become a naturalised subject in 1947.

The ‘Expressionist’ Kokoschka, deemed a degenerate by the Nazis, fled to England via Poland and Sweden in 1938, with the help of the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia. He stayed until 1953, when he moved to Switzerland. In 1959, he was appointed CBE and he received a Tate Gallery retrospective exhibition in 1962.

This monumental three-part painting is his largest in Britain. It was commissioned by his fellow Austrian émigré, Count Antoine Seilern, for a ceiling in the Count’s London house. It warned against ‘man’s intellectual arrogance’, symbolised by Prometheus (right), ‘whose overweening nature drove him to steal fire so that man could challenge the gods’. Zeus punished Prometheus by chaining him to a rock so an eagle could tear at his liver forever.

In the central panel is a vision of St John’s Apocalypse in the Book of Revelation, with its four horsemen — Conquest, War, Famine and Plague — harbingers of the Last Judgement, heading a storm from the Underworld towards the earth. The left-hand panel offers regeneration: Persephone has sprung from the clutches of Hades (a self-portrait of Kokoschka), who had abducted her, assisted by her mother Demeter, who stands between them.

Seventy years ago, Kokoschka’s fear was that science and technology threatened the freedom and individuality of mankind.

In Focus: The stunning collection of philanthropist Samuel Courtald, including Cézanne's most groundbreaking works

Courtald's collection of Impressionist works returns to The National Gallery for the first time in 70 years. Chloe-Jane Good takes

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Graham Norton's elegant East London home hits the market, and it's just as wonderful as you would expect

Graham Norton's elegant East London home hits the market, and it's just as wonderful as you would expectThe four-bedroom home in Wapping should be studied for how well it uses two separate spaces to create a home of immense character and utility.

-

Sign of the times: In the age of the selfie, what’s happening to the humble autograph?

Sign of the times: In the age of the selfie, what’s happening to the humble autograph?When Ringo Starr announced that he was no longer going to sign anything, he kickstarted a celebrity movement that coincided with the advent of the camera phone and selfie. Rob Crossan asks whether, in today’s world, the selfie holds more clout than an autograph?

-

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite painting

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite paintingAlexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, chooses an Edwin Landseer classic.

-

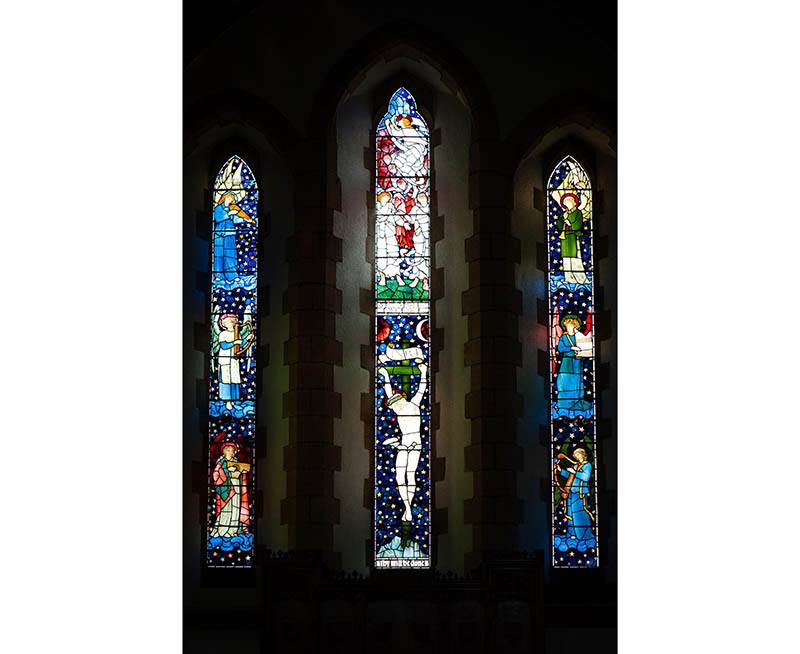

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in Britain

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in BritainThe painter Edward Burne-Jones turned from paint to glass for much of his career. James Hughes, director of the Victorian Society, chooses a glass masterpiece by Burne-Jones as his favourite 'painting'.

-

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subject

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subjectFor Country Life's My Favourite Painting slot, the writer Emily Howes chooses a work by a daring and challenging artist: Frank Auerbach.

-

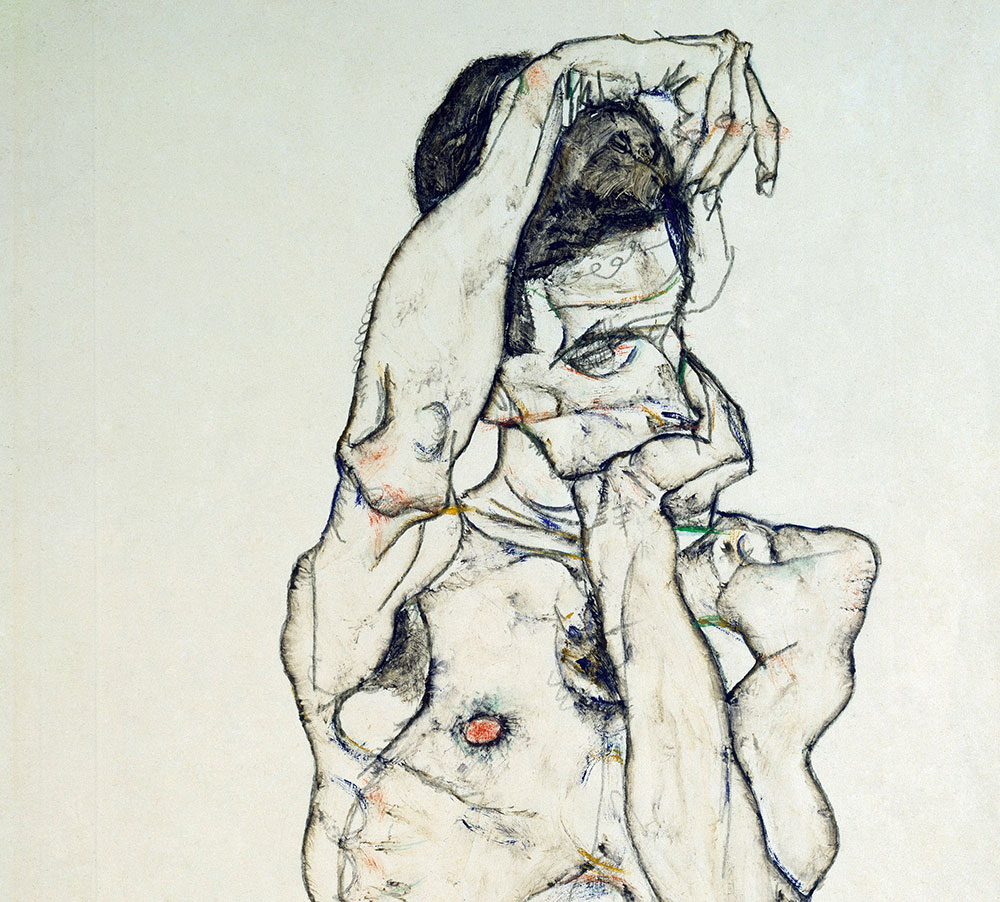

My Favourite Painting: Rob Houchen

My Favourite Painting: Rob HouchenThe actor Rob Houchen chooses a bold and challenging Egon Schiele work.

-

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson'That's why this is my favourite painting. Because it invites you to imagine'

-

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shock

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shockAs the National Gallery turns 200, the chair of its board of trustees, John Booth, chooses his favourite painting.

-

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearing

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearingChristopher Price of the Rare Breed Survival Trust on the bucolic beauty of The Magic Apple Tree by Samuel Palmer, which he nominates as his favourite painting.

-

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon'Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .'