My favourite painting: Danielle Steel

Danielle Steel, the world's top-selling fiction writer, admits that 'Klimt stole my heart' with this wonderful work.

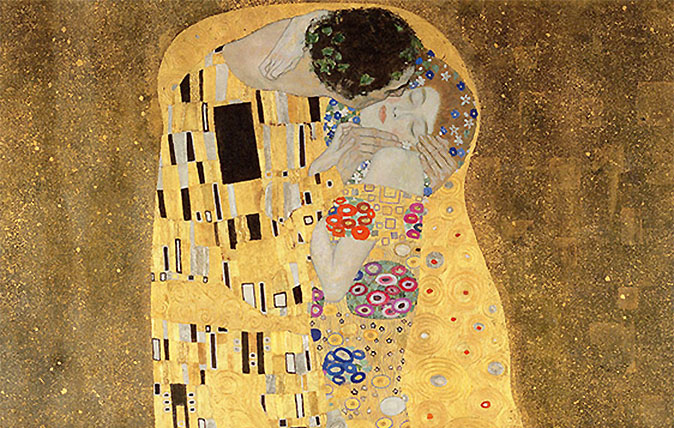

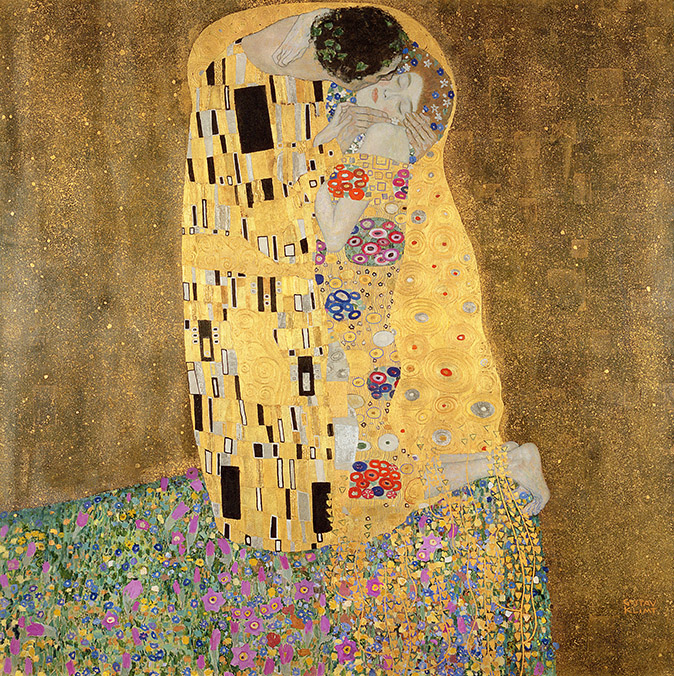

The Kiss, 1907–8, by Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), 6ft by 6ft, the Belvedere, Vienna, Austria

Danielle Steel says:

I first saw a print of this painting when I was 15. It mesmerised me: the tenderness and passion in it were haunting, the colours, the technique, the gold, the sheer beauty of his work. Klimt stole my heart. It remained my favourite painting for many years. In 1999, I wrote a book titled The Kiss and, when we chose the cover, of course, we used my favourite painting. I feel a personal tie with the painting because of it. The work still holds magic for me and always will.

Danielle Steel is the world’s biggest-selling living fiction writer. Her new novel, Against All Odds, was published last week by Macmillan

John McEwen comments on The Kiss:

Tess Jaray RA writes of Klimt in her book of essays on painting: ‘How hard it is now, looking at Klimt, to grasp the revolutionary nature of his work at the turn of the 20th century.’

Like so many, she was first attracted as a teenager to the ‘mix of fantasy and ornament… the elegance and erotic centre’, but it was only as an artist that she fully appreciated ‘the pyrotechnic skills that he used to disguise those primitive forces of pattern—surely derived from the first human expression we know of, on pots and jewellery… and from prehistoric scroll patterns and the repeated eyes of the magic fetishes of Northern Africa’.

Klimt’s desired fusion was of fine and applied art, the best of the past with an unconventional and modern vision. Ruskin and William Morris in England were precursors; Gustav Mahler, his fellow Viennese, his musical equivalent. Born into penury, at 26, he received the highest order of merit from the last Austro-Hungarian Emperor, Franz Joseph I, earned through public decorative commissions in booming Vienna, by then the sixth largest city in the world.

In 1904, censorship of a public commission made him ‘reject every form of state aid’. Liberated from commissions, and by foreign contact, his art became bolder and more ornate. His father was a goldsmith; now, he entered his own ‘golden period’, its apogee The Kiss — ironically an immediate state purchase, today possibly the world’s most reproduced work of art.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Klimt, who customarily wore a floor-length smock, here transformed into a rich robe, is shown with Emilie Flöge, his sister-in-law and confidante, in a contrastingly clinging floral dress. They are placed in an Elysian field.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher

-

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite painting

'As a child I wanted to snuggle up with the dogs and be part of it': Alexia Robinson chooses her favourite paintingAlexia Robinson, founder of Love British Food, chooses an Edwin Landseer classic.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

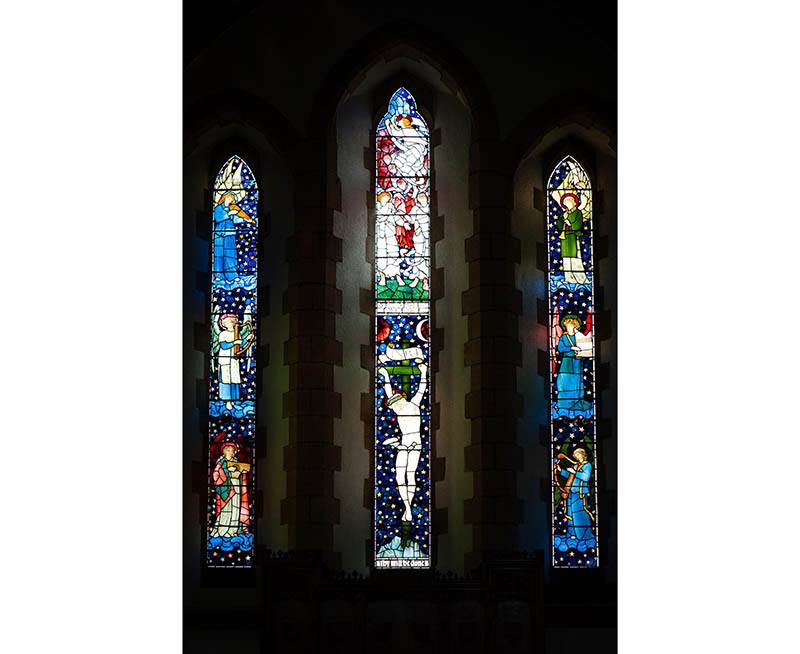

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in Britain

The Pre-Raphaelite painter who swapped 'willowy, nubile women' for stained glass — and created some of the best examples in BritainThe painter Edward Burne-Jones turned from paint to glass for much of his career. James Hughes, director of the Victorian Society, chooses a glass masterpiece by Burne-Jones as his favourite 'painting'.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subject

'I can’t look away. I’m captivated': The painter who takes years over each portrait, with the only guarantee being that it won't look like the subjectFor Country Life's My Favourite Painting slot, the writer Emily Howes chooses a work by a daring and challenging artist: Frank Auerbach.

By Toby Keel

-

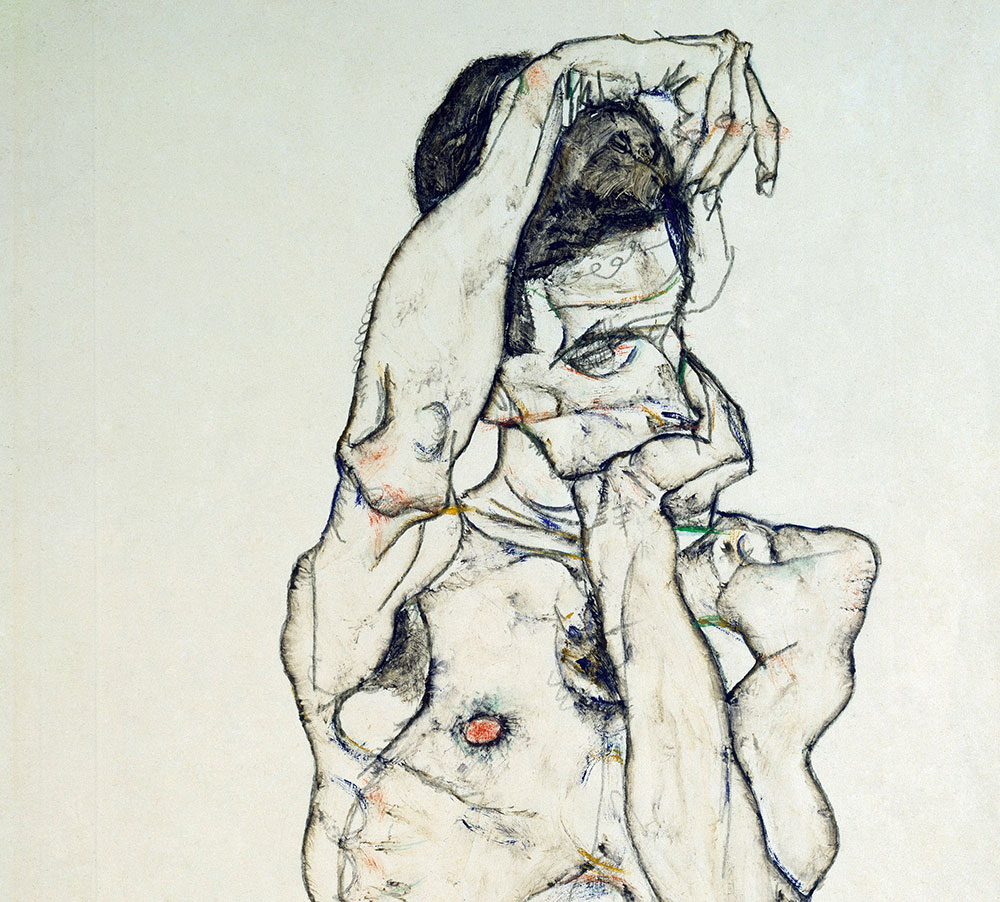

My Favourite Painting: Rob Houchen

My Favourite Painting: Rob HouchenThe actor Rob Houchen chooses a bold and challenging Egon Schiele work.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson

My Favourite Painting: Jeremy Clarkson'That's why this is my favourite painting. Because it invites you to imagine'

By Charlotte Mullins

-

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shock

The chair of the National Gallery names his favourite from among the 2,300 masterpieces — and it will come as a bit of a shockAs the National Gallery turns 200, the chair of its board of trustees, John Booth, chooses his favourite painting.

By Toby Keel

-

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearing

'A wonderful reminder of what the countryside could and should be': The 200-year-old watercolour of a world fast disappearingChristopher Price of the Rare Breed Survival Trust on the bucolic beauty of The Magic Apple Tree by Samuel Palmer, which he nominates as his favourite painting.

By Charlotte Mullins

-

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon

My favourite painting: Andrew Graham-Dixon'Lesson Number One: it’s the pictures that baffle and tantalise you that stay in the mind forever .'

By Country Life