My favourite painting: Ann Christopher

'I do remember being moved to tears—not in a depressive way, but with powerful emotion'

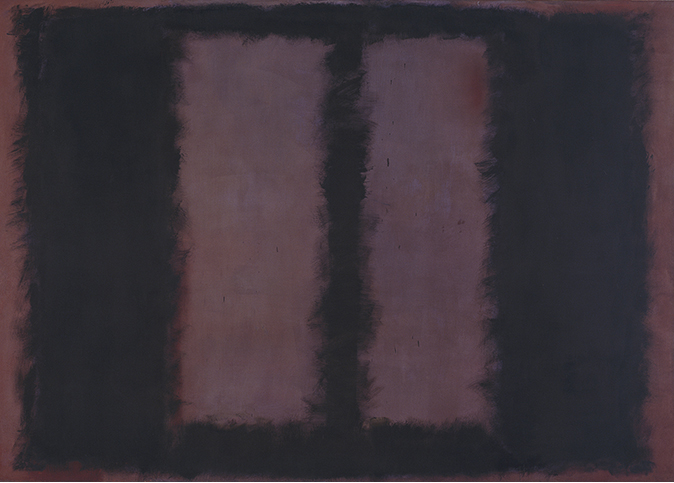

Black on Maroon, 1958, by Mark Rothko (1903–70), 150in by 105in, Tate Modern, London

Ann Christopher says: I have to choose a group of paintings as they are, to me, one work. Walking into a room in Tate Britain in the 1970s was the first time I experienced an overwhelming reaction to painting. At the time, I knew little of Rothko and the journey of those painting, but I do remember being moved to tears—not in a depressive way, but with powerful emotion. Rothko’s paintings still have the ability to draw me to them and move me. They have an extraordinary sense of depth both physically and mentally—a sense of mystery as if one is looking inside one’s head.

Ann Christopher RA is a sculptor. Her exhibition ‘All the Cages Have Open Doors’ opens at Pangolin London, Kings Place, London N1, on November 2, 2016

John McEwen comments on Black on Maroon: For half a year, Mark Rothko worked on a set of abstract paintings to decorate the swanky Four Seasons restaurant in the new Seagram building on Park Avenue, New York. It was a sign of his growing fame that he received such a showy commission; nonetheless, he accepted it grudgingly ‘with strictly malicious intentions’, taking welcome payment up front, but insisting on a break clause, because he privately despised everything the restaurant represented.

He wanted his individual but all maroon-based paintings to form a ‘single place’, the clientele of ‘rich bastards’ to feel trapped. To this end, he worked within a frame of the restaurant’s dimensions temporarily erected in his studio.

As the saying went, you can take a Jew out of the shtetl, but not the shtetl out of a Jew. Born Marcus Rothkovitz, Rothko knew shtetl life. In his Russian childhood, he had experienced the Tsar’s persecution, with a lifelong facial scar from a Cossack’s whip to prove it. Arriving in the USA at 10, without money or English, he had suffered a refugee’s humiliation; dependent on successful uncles, he felt the anger of a poor relation. His artistic struggle was long. In 1958, his studio was still in Manhattan’s rundown Bowery district. For work, he dressed like a tramp and thought it obscene to spend more than $5 on a meal.

One meal at the Four Seasons proved enough. He broke the contract. England’s foremost contemporary art collector, E. J. (‘Ted’) Power, alerted Sir Norman Reid, Tate director, to the pictures’ availability. Nine were eventually presented by the artist, of which this is one. They arrived at the Tate the day he committed suicide in New York; a fitting lamentation.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

My favourite painting: Nicholas Cronk

'I like the fact that the painter, Huber, has cheekily seated himself on the great man’s left.'

My favourite painting: Marco Forgione

'I fell completely in love with this painting because of its sheer joy, movement and carefree energy.'

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.