Michaelangelo: The good, the bad and the disturbingly ugly of one of art's greatest geniuses

With a passion for arguing and a sharp tongue to match his extraordinary genius, Michelangelo was both the enfant prodige and the enfant ‘terribile’ of the Renaissance, as Michael Hall reveals.

Some time in the early 1490s, a fight broke out in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, Italy, among a group of teenage boys who were copying the famous frescos by Masaccio as part of their training to be artists. One had gone too far with his mocking banter about the others’ abilities and provoked an older boy to punch him in the face, breaking his nose. It was the most famous punch in the history of art. The younger boy was Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) and his assailant was Pietro Torrigiani (who later worked in England). When describing the incident to another Florentine sculptor, Benvenuto Cellini, Torrigiani laughed that he had felt Michelangelo’s ‘bone and cartilage crush like a biscuit. So that fellow will carry my signature till he dies’. He was right: Michelangelo’s broken nose can clearly be seen in portraits of him made nearly 70 years later.

Torrigiani claimed that he lost his temper (‘more than usual’, he said) because of Michelangelo’s ‘habit of making fun of anyone else who was drawing’ in the church. This is plausible. Throughout his life, the latter had a reputation for sardonic humour that often tipped over into rudeness. When he was young, this may perhaps have been compensation for being shorter than average and slightly built — he was described as thin and sinewy, not well built and muscular (as Torrigiani was). His sharp tongue was an aspect of what became an intimidating personality. Pope Leo X, who was both a patron of Michelangelo and a friend — they had grown up together in the household of Leo’s family, the Medici — described him in 1520 to the artist Sebastiano del Piombo as ‘terribile’. Although devoted to Michelangelo, he said, even he — the Pope — was frightened of him.

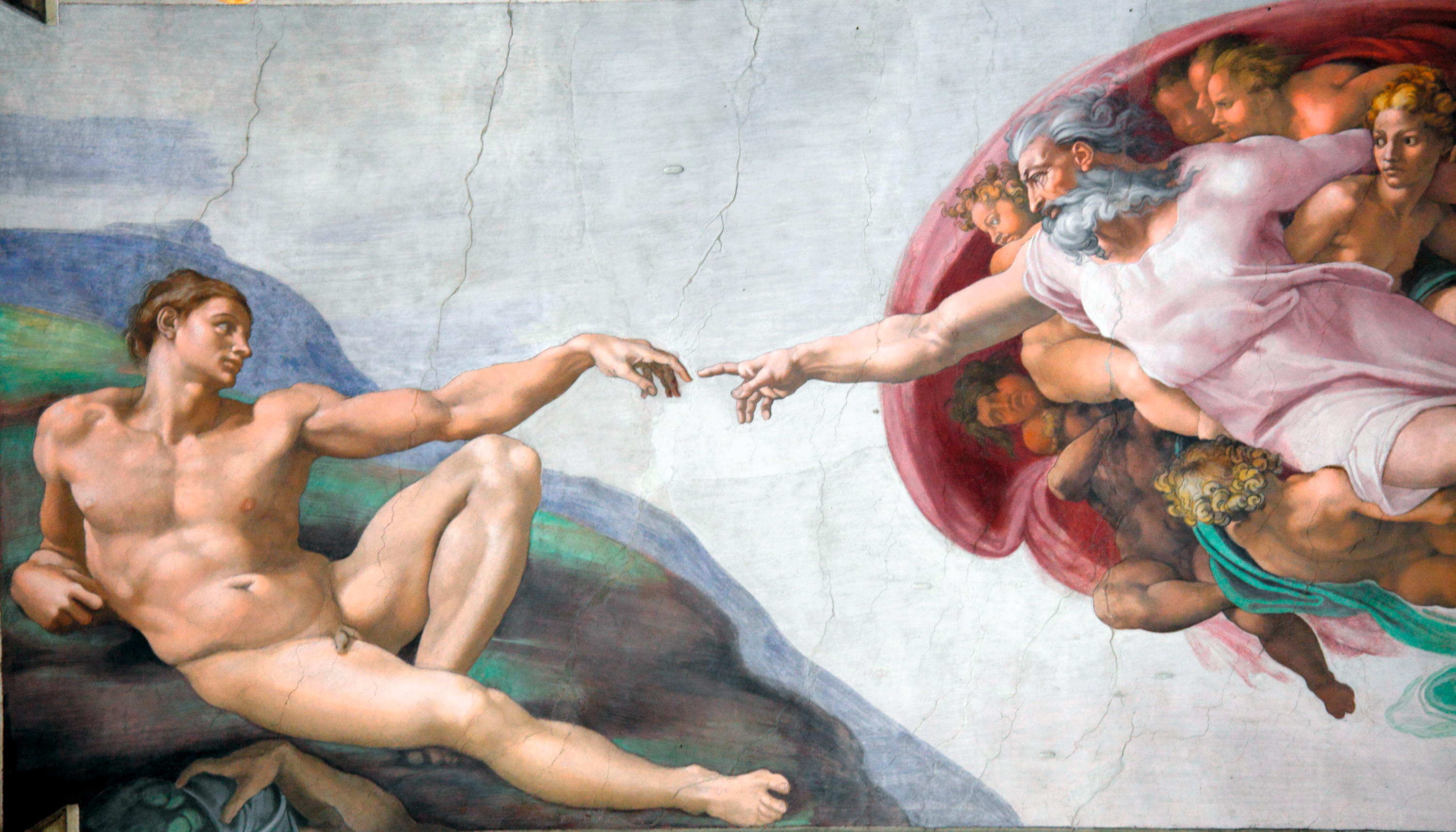

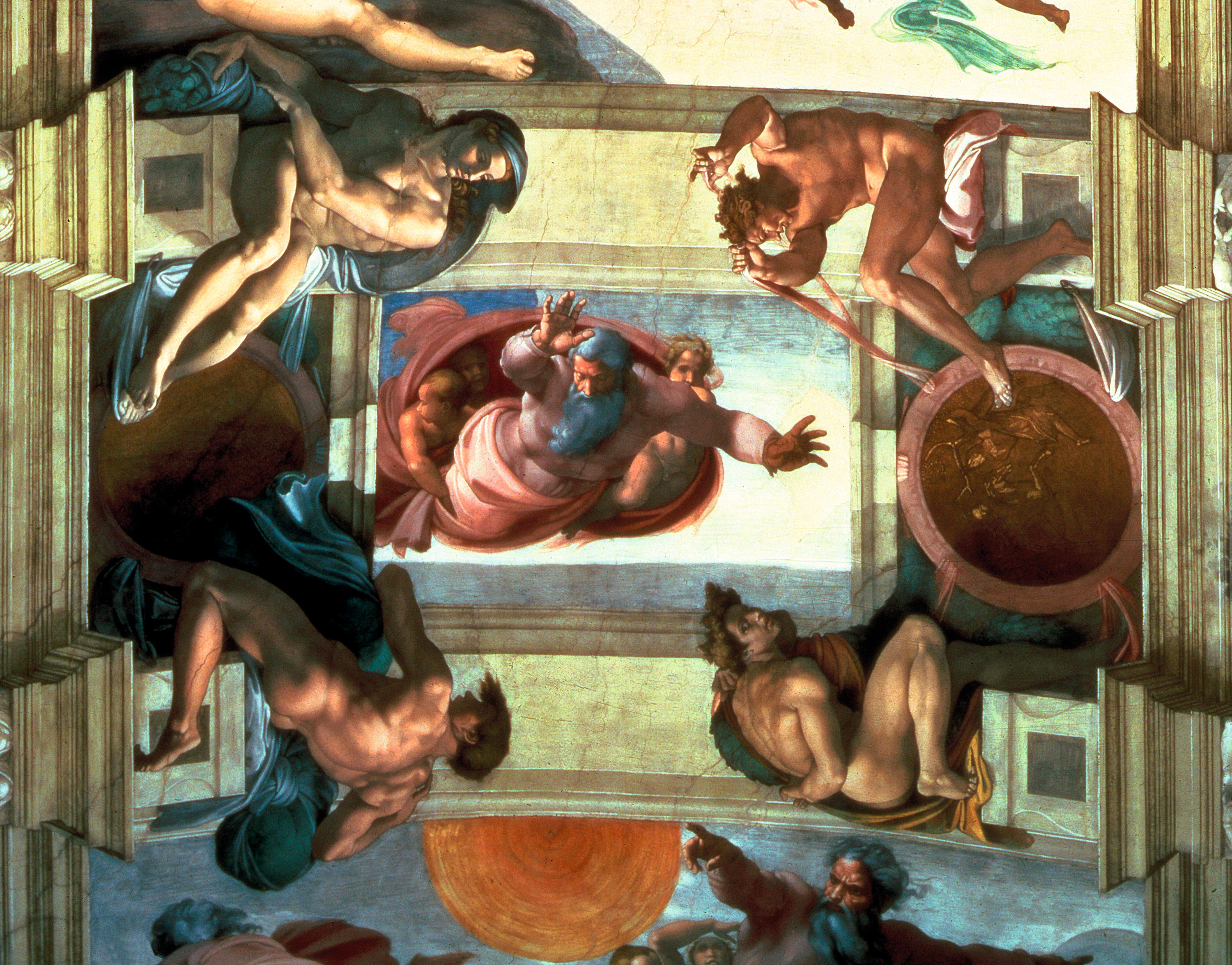

'God separating the land from the sea' on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel has been inspiring awe and wonder for half a millennium.

Terribile in this instance probably means something like ‘impossible’, as the remark was prompted by Leo’s weariness with Michelangelo’s habit of arguing about everything. Sebastiano replied that this ‘terribilità’ was only the result of Michelangelo’s passionate involvement with the great projects entrusted to him. Terribilità can mean ‘awesome’ or ‘sublime’, terms that were readily applied to Michelangelo’s major achievements, thus linking the artist’s character to his works. Although it would be anachronistic to see his art simply as an expression of his personality, the concept of terribilità undoubtedly links key aspects of his career, notably his insistence on being seen as an isolated genius and his ferocious competitiveness. Those qualities were combined with relentless ambition, which was on a scale that led to a long sequence of unfinished works, as well as some of the greatest art ever created.

Michelangelo was the subject of two full-length biographies in his lifetime. One, by Ascanio Condivi, was written under his close supervision; the other was included by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists. Vasari, who worshipped Michelangelo, begins with a passage that announces the arrival of a new archangel, if not a Messiah: when the artist was born, on March 6, 1475, ‘without further thought his father decided to call him Michelangelo, being inspired by heaven and convinced that he saw in him something supernatural and beyond human appearance’. This reflects Michelangelo’s wish in old age to be regarded as an artist who owed everything to innate ability and little or nothing to his training. Condivi’s biography ignores the information given by Vasari that Michelangelo fought with his middle-class family to be allowed at the age of 13 to take up an apprenticeship in the leading workshop in Florence, run by painter Domenico Ghirlandaio.

The great sculptor caused centaurs and lapiths to writhe from their restricting marble.

That Michelangelo did, in fact, have a good deal to learn is demonstrated by the survival of some of very early drawings, including ones that he made in Santa Maria del Carmine, possibly with Torrigiani at his side. Judged simply as exercises in draughtsmanship, they are awkward, but they convey a sense of three-dimensional presence that helps to explain Michelangelo’s decision to abandon Ghirlandaio for the sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni, who ran an informal school in the Medicis’ sculpture collection. In old age, Michelangelo readily acknowledged his debt to the Medici, but there is — pointedly — no reference in Condivi’s biography to Bertoldo. That Michelangelo studied his work closely is evident from his unfinished marble relief known as The Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, carved when he was in his late teens. It clearly reflects his knowledge of ancient Roman sarcophagi — the sort of model encouraged in the cultivated antiquarian circles around the Medici — but was also influenced by a bronze relief of a battle by Bertoldo.

Michelangelo’s almost frantically energetic relief foretells a key aspect of his work in being composed of nude men. Although no other artist has matched his achievements across a range of media — his genius was expressed in painting and architecture, as well as sculpture — in terms of subject matter, few have been so narrow. He focused almost exclusively on the heroic male nude, which was in his eyes the highest possible subject, as man (not woman) was made in the image of God. Before he was 30 years old, he created the most famous embodiment of youthful male courage in western art, David.

Noble David emerged from a single huge block of stone.

The statue was unveiled in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence in 1504 to enthusiastic acclaim, not only for its beauty, but also the sculptor’s skill in overcoming the difficulties of carving such an enormous work from a damaged block of stone. For Michelangelo, his success in meeting that challenge was comparable to David’s victory over Goliath: although the sculpture is not a self-portrait, it reflects the artist’s identification with the young hero.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Soon after completion of David, Michelangelo encountered Leonardo da Vinci, who had recently returned to Florence from Milan, leaving behind an unfinished monumental bronze equestrian statue. He was talking to a group of friends in the street about a puzzling passage in Dante’s Divine Comedy when one of the men spotted Michelangelo and asked for his help. Leonardo, who was well known for his courtesy, deferred to the younger artist, but Michelangelo turned on him rudely: ‘No, you explain — you who have undertaken the design of a horse to be cast in bronze, but were unable to cast it, and were forced to give up in shame.’ In other words, there was only one successful sculptor of monumental works in town.

As a student copying from Masaccio’s frescos in brown ink, Michelangelo’s genius and irascibility were in evidence when he teased another boy, Torrigiani, who punched him

This rivalry was exploited by Florence’s governing council when it invited both artists to paint frescos in the great hall of the Palazzo della Signoria, but Leonardo’s was abandoned after he encountered technical problems and Michelangelo’s was never begun, as he had been summoned by the then Pope, Julius II. The most famous outcome of his move to Rome was the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The four years that he spent on this epic project, from 1508–12, were marred by his venomous rivalry with Raphael, then painting frescos in the papal palace. Eight years his junior, Raphael was everything that Michelangelo was not: charming, good looking and a great success with women. He was also a virtuoso painter in fresco. Michelangelo had not painted frescos since his apprenticeship with Ghirlandaio, so he summoned artists from Florence to help. Although Vasari explains that these men — whom he names — were rapidly dismissed, Michelangelo hated any suggestion that he had not worked alone and did not allow Condivi to mention his initial appeal for assistance. He was only too happy, however, to have it noted that Raphael had stolen ideas from him.

The initial reason for Michelangelo being summoned to Rome was to make a tomb for the Pope. This project was to cause the sculptor endless grief, as, for decades after Julius II’s death in 1513, his family pursued Michelangelo to get the tomb finished or to return the payments for it. The main problem was that his design was wildly over-ambitious: it was to include no fewer than 40 figures in marble, as well as large reliefs in bronze. Even Michelangelo acknowledged that his ambition often outran what was humanly possible: Condivi records that, when quarrying marble at Carrara for the tomb, he conceived only half jokingly the idea of sculpting a mountain top into the form of a man.

By then, Michelangelo was leaving behind him a succession of incomplete sculptures, beginning in 1505 with St Matthew, intended for Florence Cathedral. Such works have a strong appeal to modern taste, as an expression of Michelangelo’s energy and an aspect of his terribilità. This can obscure the fact that he intended his sculptures to have a very high degree of finish, as demonstrated most famously by his Pietà in St Peter’s.

That aesthetic ideal of surface perfection is evident in some of his drawings. Almost all the 600 or so that survive are sketches in preparation for paintings, sculptures or buildings, but, in the early 1530s, he made a few to which he gave the highest finish he could muster. Works of art in their own right, most were intended as gifts for a Roman nobleman of great beauty, the young Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, with whom he had fallen passionately in love. In a sequence of sonnets addressed to Tommaso — Michelangelo was also one of the major poets of his age — he insisted that his devotion was chaste and, although this cannot be doubted, the extraordinary care that he devoted to these drawings and poems suggests the often anguished depths of the emotional life that underlay the terribilità of both his art and personality.

Footnote: Revenge is a dish best-served in one of art's great masterpieces

Michelangelo’s rather cruel sense of humour occasionally spilled over into his art. When he was painting the Last Judgement on the altar wall of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel in 1536–41, the nudity of the figures was criticised by the Pope’s master of ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena, described by Vasari as ‘a very high-minded person’. In revenge, Michelangelo portrayed him as one of the damned souls, his naked body entwined by a serpent.

Biagio complained to the Pope, Paul III, who is said to have replied that, unfortunately, he could do nothing, as his writ did not extend to Hell.