Life, the universe, cave art... and no longer believing in Heaven, by Robin Hanbury-Tenison

Does the meaning of life hide in our mystical relationship with our world, as captured by the cave art of prehistoric men, asks Robin Hanbury-Tenison.

I no longer believe in an afterlife, at least not one as expressed by the usual images of Heaven and Hell, and most thinking people probably don’t either. However, I do believe that I will live forever as part of the vast molecular system of which I am composed. My ‘soul’, or whatever lives on, will not be preoccupied with the petty issues of politics and family, but with eternity. I find our increasing awareness of the complexity of life on earth and our gradual recognition that understanding everything is still far beyond the capacity of our human brains — which are often described as the most sophisticated organisms ever produced — rather comforting, as it explains for me why we cannot yet come to terms with what happens after death.

The idea that we really may be part of something so much bigger and more complex than we can imagine and that all may be revealed when we return to our basic organic material accords well with our growing realisation that we don’t really exist anyway and are merely an accumulation of molecules surrounding a passage, through which nourishment passes. When that relationship ceases through accident, illness or old age, the molecules continue to live, pushing up the daisies or entering the atmosphere and becoming something else.

Suddenly, it all seems less worth worrying about; instead, we should enjoy every second of what we have. Let’s face it, we would be hard put to imagine a better world than the one we have, when it is working properly and we are not wrecking it. Sitting on a cloud playing a harp sounds pretty pale compared with living in the Garden of Eden Nature provides us with, if given half a chance.

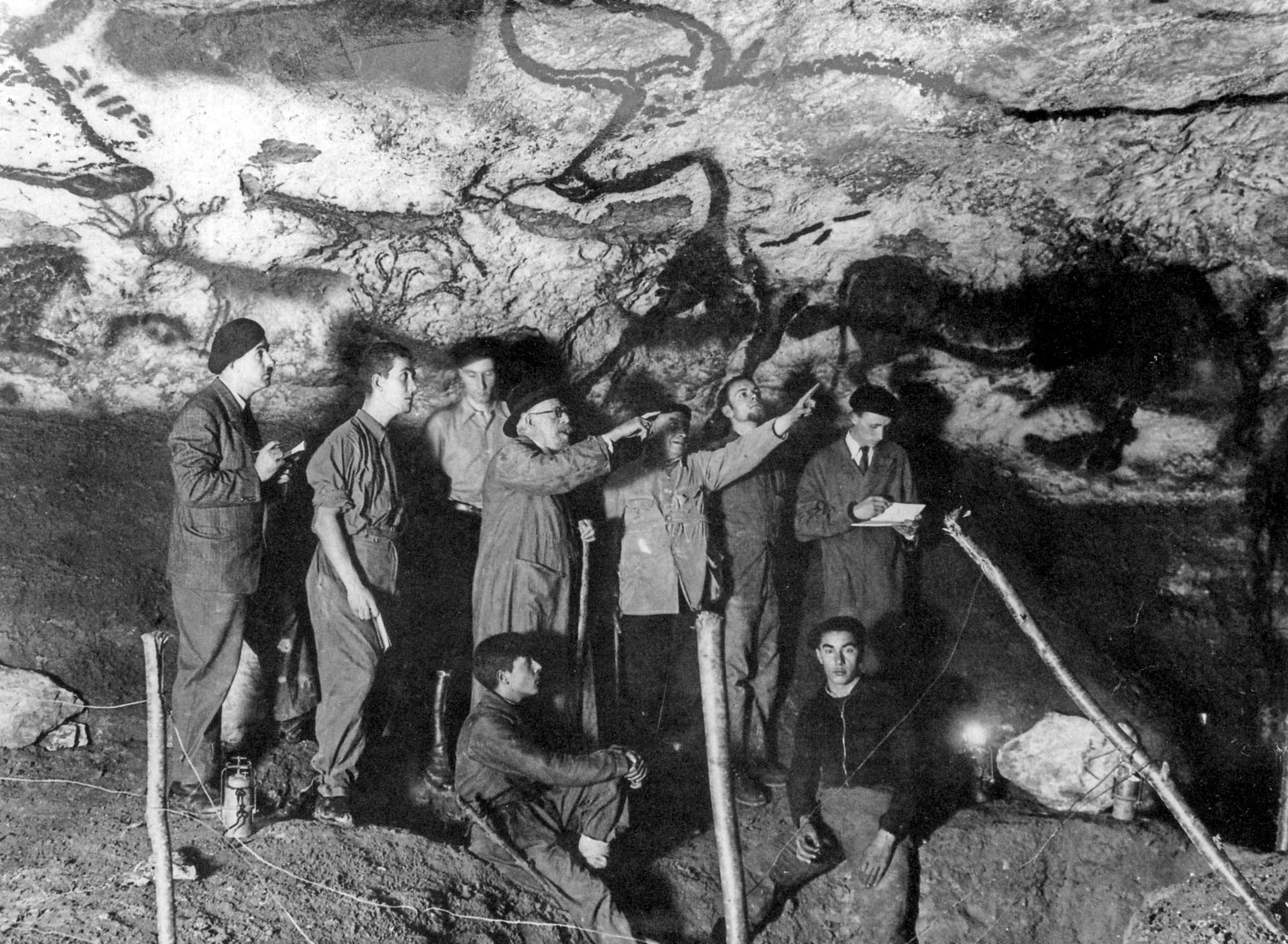

About 30,000 years ago, something remarkable happened to the human brain. Perhaps it happened long before that, as it seems to have been the same size as it is now for perhaps 200,000 years since we evolved into Homo sapiens. Yet, 30,000 years ago, we started recording our existence, demonstrating our awareness of self by painting and engraving sensational pictures deep underground. To reach the deepest and earliest of these, such as Lascaux and Altamira, often involved crawling through up to a mile of convoluted narrow passages into large natural caverns.

No one knows why our ancestors felt it necessary to go to these inaccessible sites, lit only by flickering tapers, to paint their pictures, but the whole operation must have had a deep spiritual meaning. The sites must have held special significance, too, as the art is spread over thousands of years. People surely made those arduous journeys time and again over the millennia for a reason — and that seems to have been spiritual.

The extraordinarily beautiful depictions of mammoths, bison, wild horses, bears and human figures, one even clad in a skin and playing a flute, must have meant something and the only conclusion I can draw is that it was part of a ritual. Many images show men confronting animals with their arms upraised and, apparently, in a trance. These are probably shamans under the influence of hallucinogenic drugs. Isn’t it amazing that only now, millennia later, is the study of these and the potential their use may have for medicine and mental health becoming respectable?

There is an extraordinary similarity in descriptions from all over the world of the shamanistic experience. From the Western European caves, where they were first depicted, to the anecdotal accounts of shamans in Siberia and all through the Americas; from the Paleolithic Age, perhaps 2.5 million years ago, right up to recent times — and even in remnant communities today — shamans have described flying through the air, communicating with, and sometimes becoming, spirit animals and generally experiencing a quite different reality from the familiar world around us. I have seen this myself many times when visiting remote tribes in South America and South-East Asia.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

When I contracted covid, I was heavily drugged and put in a coma for five weeks. The result was that, mercifully, I have almost no recollection of all the nasty things being done to me to keep me alive. What I do remember is the hallucinations I experienced as a result of the drugs. I saw long, green snakes slithering over the foot of my bed, brown bats crawling up the lead to my saline drip and a tawny jaguar that I could reach out and stroke. These illusions did not scare me, as I realised that I was in the same place as all those shamans I had watched over the years; I found it interesting and rather comforting.

What the cave art of southern France and northern Spain reveals is that humans were, perhaps for the first time, seeking to make sense of the world around them. Up to this point, as far as we know, we were simply rather clever animals, who, for a few hundred thousand years, had been making our way in the world by being a bit more skilled at using tools, hunting and perhaps manipulating fire.

Very gradually, we were eliminating the competition — similar species, such as the Neanderthals — and setting off on the long road to world dominance, which we have now achieved with a vengeance. These were hunter-gatherer societies, which depended largely for their survival — as, indeed, has almost every other species of life — on killing for food. Perhaps what marked out humans as different was that we began to find this disturbing. Perhaps the mystical relationships people who had entered the spirit worlds of animals had developed with their hosts made them uneasy about slaughtering them.

Hunting was and still is surrounded with taboos and prohibitions. The Bushmen of the Kalahari feel a deep empathy with their prey and so, I have found, did all the tribal people I have known. There is a love and need relationship between man and his prey. I have watched a Mentawaian hunter on the island of Siberut off the coast of Sumatra praying with a loving intensity to the spirit of the deer he intends to kill the next day, urging it to succumb to its fate and fall to his spear. Animal sacrifice has been a central rite of nearly every religious system in antiquity and this must have come from prehistoric hunting ceremonies, continuing to honour a beast that gave its life for the sake of humankind.

For the next 20,000 years of our existence, until settled agriculture became the norm, this was how we saw the world and these pictures are the only indication of what people were thinking and what we were worshipping. It seems that religion and art were inseparable from the very beginning.

Robin Hanbury-Tenison is an explorer, a Royal Geographical Society gold medallist and an author. His most recent book is ‘Taming the Four Horsemen’ (2020)

Images: Alamy

Cheddar Gorge and The Mendips AONB: The landscape that inspired ancient cave painters, William Blake and a thousand magnificent photographs

Local legend has it that Jesus Christ himself once walked the green hills of the Mendips — and while that tale

In Focus: Billy Childish's poignant, tender depiction of his wife, completely idiosyncratic and entirely compelling

Billy Childish's art is both outstanding yet often misunderstood — something that an exhibition in Margate's Carl Freedman Gallery looks

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.