In Focus: Walter Sickert, the artist who dragged Modern Art into Victorian Britain

Walter Sickert introduced Victorian Britain to Modern art, yet is best known for his drab-toned nudes on iron bedsteads. Mary Miers considers the career of an individualist who was both radical and charming.

When, in the late 1880s, Walter Sickert began painting London music halls, he brought to a genre made fashionable in the 18th century a unique insight, as well as a daringly modern focus. For, unlike his famous predecessors who painted theatrical subjects, such as Zoffany and Hogarth, Sickert had actually worked as an actor, playing minor roles in London theatres and on tour. By then a full-time painter, he was drawn to the raucous world of what was a cult attraction of Victorian working-class life. Returning each night to venues such as the Bedford Music Hall and Gatti’s Hungerford Palace of Varieties, he made discreet sketches and befriended the artistes.

Sickert — who is the subject of an exhibition at Tate Britain this summer — wanted to explore progressive French ideas through his own adventurous versions of Degas’s and Manet’s stage and café-concert scenes, but early depictions, such as Le Lion Comique, were vilified by the critics. They could find none of the ‘pictorial beauty’ that Sickert sought to express through his strangely cropped compositions, with their blurred boundaries, bold treatment of low tones and open-mouthed figures revelling in the ribald acts.

Soon, he widened his angle of vision from the stage and stalls to include the auditorium, creating complex paintings that made clever use of mirror reflections in the manner of Velázquez. Then, he turned the spotlight onto the audience, depicting views of the gallery from spectacular angles, as in Gallery of the Old Bedford of 1894–95, with its gawping figures in bowler hats framed by glinting architectural detail. These pictures are a rare record of a vanished world; only at the Gaîté Montparnasse in Paris, which Sickert painted in about 1907, can an original working interior still be seen today.

Theatrical elements ran through Sickert’s person, as well as his art. Vivacious and witty, he was a great performer and adopted successive guises, from dandy to rustic, regularly restyling his famously handsome looks with different beards and hats. He was fascinated by ambiguity, murder mysteries and the haunts of criminals and would even become the subject of an unfulfilled mission to prove he was Jack the Ripper.

The oldest child of a Danish painter and his English wife, Sickert was born in Munich, Germany, in 1860 and spent his early years in Bavaria, before the family moved to London. His formative influence was James McNeill Whistler, whose Chelsea studio he joined as an assistant in 1882. There, he was grounded in etching and tonal harmony and learnt to value the craft of painting.

Sickert’s early enthusiasm for the work of Punch illustrator Charles Keene instilled a commitment to draughtsmanship and illustration. In France in the 1880s, Degas encouraged him to create more defined compositions, to include figures and to expand his colour range. The artist began to build up thin layers of paint in a pattern over the preparatory drawing and to touch on Impressionism — but Sickert was always a studio artist, more interested in technique than plein air naturalism.

He was at the centre of an avant-garde circle that sought, through various groups and exhibiting societies, as well as writing and teaching, to shake up the staid world of British art. At the New English Art Club (NEAC), which he joined in 1888, he and others, including Philip Wilson Steer and Sidney Starr, aimed to introduce a fresh approach to painting informed by developments in France. ‘It will be the place I think for the young school of England,’ Sickert wrote; however, although shows such as the ‘London Impressionists’ of 1889 attracted much attention, the reviews were largely negative.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Restless and cosmopolitan, Sickert moved ceaselessly between rented homes and studios, his main painting grounds being London, Bath, Venice and Dieppe. He married three times (but had no recorded children) and, despite multiple infidelities, continued to rely on the financial support of his wives — he was always broke, largely thanks to his own fecklessness — as well as their long-suffering friendship and moral strength.

After a period painting portraits in the English capital, he moved to Dieppe, where he lived from 1898 to 1905. Here, he focused on what he called ‘picturesque work’ — unchallenging townscapes capturing the architectural charms and scenic views of Dieppe and Venice. Painted with a freer, more expressive hand and often brighter palette, these did well. Thanks to the painter Jacques-Émile Blanche, Sickert became well established in the French art market and salons and met the leading Paris dealers.

In turn, Blanche introduced his friend to the cultivated circle that gravitated to Dieppe, which included Degas, Pissarro and Monet. The town also attracted a coterie of upper-class British visitors and among the Society women with whom Sickert struck up long-term friendships was Lady Blanche Hozier, to whose future son-in-law, Winston Churchill, he would later give painting lessons. It was typical of his bohemian nature that, although socialising among Dieppe’s fashionable summer set, he resided with his fishseller mistress in the rough harbour quarter.

The gritty reality of urban working-class life held an irresistible allure for Sickert. Having challenged the conventions of the idealised female body with a series of ‘risque nudes’ made in Venice using prostitutes as models, he continued to explore the theme in his Camden Town studio from 1905, painting intimate scenes of naked women in shabby bedsits redolent of Degas and Bonnard. He sought to extract a ‘magic and poetry’ from this drab and seedy world, yet also to shock.

Famous among his ‘conversation pieces’ was the ‘Camden Town Murder’ series of bedroom scenes depicting a clothed man with a naked woman, made in 1908–09. He gave them alterative titles, relishing the way a name could change a picture’s dramatic tension.

In 1907, Sickert established an offshoot of the NEAC with Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman and others, calling themselves the Fitzroy Street group after the shared studio where they held Saturday openings. Their focus was everyday subjects: ‘The more our art is serious, the more will it tend to avoid the drawing room and stick to the kitchen.’

But Sickert’s work continued to sell better in France than in England, where the public was still easily shocked. He was briefly involved with the more ‘advanced’ Camden Town and London Groups, but was unenthused by the output of the younger generation and, increasingly, became an independent figure in the artistic firmament.

As a pioneering link to the French avant-garde, Sickert was, however, revered. The 1920s saw his work being bought by public collections. He became president of the Royal Society of British Artists and, in the last decade of his life, exhibited at leading London galleries. In 1930, the Daily Mail declared him ‘Our Greatest Living Painter’.

With unflagging verve, Sickert continued to seek new stimuli and to explore radical ways of depicting modern life through figuative painting. In the late 1920s, he dramatically changed style, producing his ‘Echoes’ series based on Victorian prints and developing a bold new approach using photography.

The painter died peacefully, sitting in his chair at his house in Bathampton, Somerset, in 1942. His art would go on to inspire generations of radical ‘schools’ and individuals, notably Andy Warhol and the Pop artists and the ‘School of London’ painters Auerbach, Bacon and Freud.

‘Walter Sickert’ is at Tate Britain, London SW1, until September 18 — 020–7887 8888; www.tate.org.uk

In Focus: How British artists contributed to the uncanny, desirous world of Surrealism

Michael Murray-Fennell delves into the subconscious, the uncanny, war and desire and discovers the contribution made by British artists to

In Focus: The work by a Bloomsbury Group stalwart which fuses nature, nostalgia and Impressionism

Britist artists Duncan Grant's wonderful versatility allowed him to mix traditional and modern, natural and man-made, as this picture on

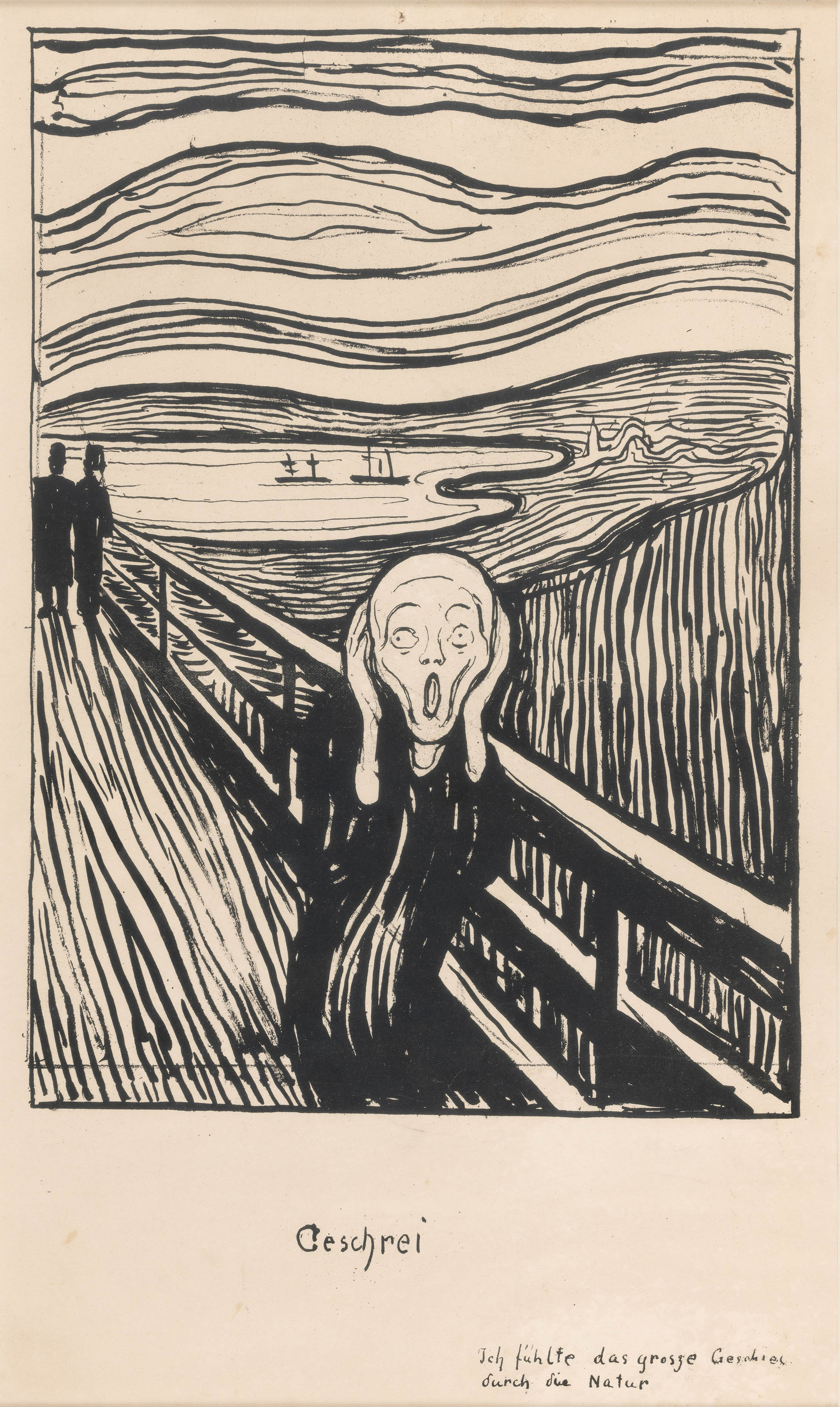

In Focus: A haunting monochrome printing of The Scream which bears Munch's own description of its meaning

The British Museum is currently running its largest exhibition of Edvard Munch's prints in almost half a century — and naturally,

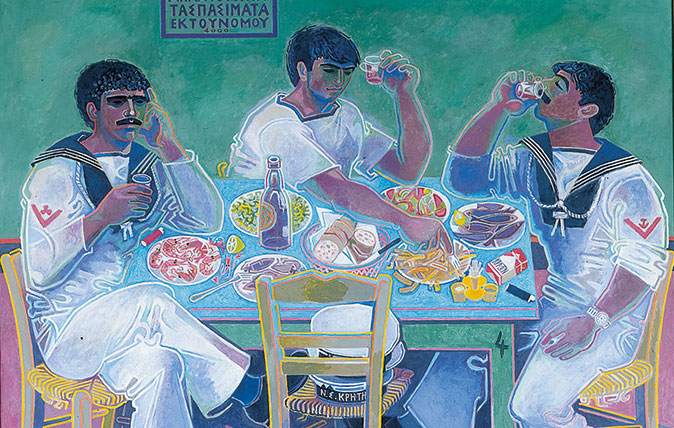

In Focus: The charmed life of Paddy Leigh Fermor and friends in Greece

The iconic writer Paddy Leigh Fermor and two of his friends in Greece – both artists, one a local man and

Mary Miers is a hugely experienced writer on art and architecture, and a former Fine Arts Editor of Country Life. Mary joined the team after running Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. She lived in 15 different homes across several countries while she was growing up, and for a while commuted to London from Scotland each week. She is also the author of seven books.

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher