In Focus: The Suffolk sculptor who ended up rubbing shoulders with Laurie Lee, Lucian Freud and George Melly in 1960s London

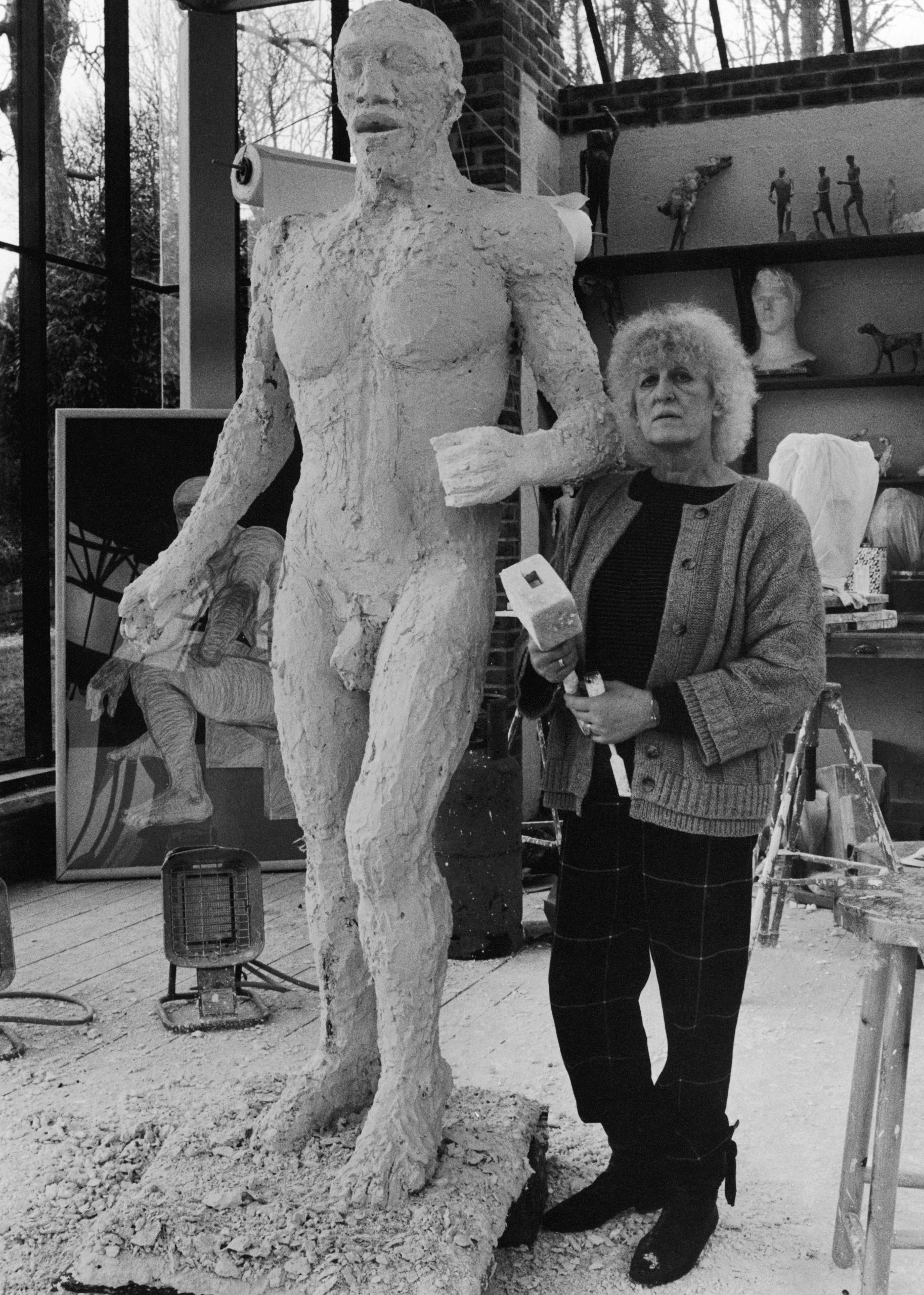

The sculptor Elisabeth Frink (1930–93) responded to the climate of the Cold War with powerful works exploring man and beast as predator and prey. As her work undergoes a timely reappraisal, Mary Miers considers her career.

Dame Elisabeth Frink was the first female sculptor to be elected a Royal Academician (in 1977) and her public commissions number 38, from Blind Beggar and his Dog (1957) in London’s Bethnal Green to the monumental Risen Christ, installed at Liverpool Cathedral a week before her death.

Yet, perhaps in part because she was a woman in a still male-dominated world and because she made figurative bronzes when Abstract art and Conceptualism were in fashion, until now, she has been under-represented in public galleries and museums. This, in spite of the extraordinary expressive power and originality of her sculpture, through which she explored the themes of humanity and Nature that preoccupied her through her life.

Frink acquired a deep love and knowledge of the natural world growing up in rural Suffolk, where she learnt to ride aged four. She had an instinctive affinity with animals and was fascinated by the behavioural instincts they share with humans and their depiction in art as ancient as cave paintings.

Her later representations became more gentle and naturalistic, but she was interested in the darker side of the animal and human world, the brutality as well as the affection. ‘Her animal sculptures are tortured, split and rigid with fear,’ stated a review in 1952, and her 1955 solo show at St George’s Gallery, London, included a decayed looking Horse’s Head and other distorted and writhing creatures.

Still more unsettling are her hybrid bird sculptures, from the early corvid-monsters that brought her to prominence after she graduated from Chelsea School of Art to the walking humanoid ‘Warrior Birds’ she made from 1953 — ‘Jagged as shrapnel, these forms are both wounds and weapons… if they sang they would spit out splinters of iron,’ wrote her friend Laurie Lee — and the more militarised ‘Harbinger’ and ‘Standard’ series of the 1960s. Just as du Maurier’s haunting novel The Birds (1952) is a metaphor for nuclear war, and other artists adopted avian imagery in response to the climate of fear, Frink’s menacing man-birds were, she wrote, ‘vehicles for strong feelings of panic, tension, aggression and predatoriness’.

Her preoccupation with conflict, heroism and trauma was forged during her wartime childhood, when she witnessed returning planes and aviators falling in flames from the sky. In an echo of Ted Hughes’s poem The Hawk in the Rain (1957), she produced a series of sculptures and drawings of falling, spinning men with mutilated bodies and pitted flesh, images of ‘human vulnerability on a celestial scale’.

She was fascinated by flight, the exploration of Outer Space and the aeronautical romantic Léo Valentin, whose descent to death in 1956 partly inspired Birdman (1959). Visiting Paris in 1951, she had been greatly taken by Rodin’s skill at representing the body in motion and influenced by seeing Alberto Giacometti’s attenuated forms and Germaine Richier’s metamorphosing figures. She adopted their technique of modelling in plaster over a wire armature and later met Richier, who became a role model.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In another distinctive body of work, Frink explored the contradictory forces of human behaviour through archetypal male figures, from her smooth, sinister ‘Goggle Heads’ of 1967–69, monuments of sexual prowess and thuggish aggression, to her ‘Tribute’ and ‘Memoriam Heads’ of the mid 1970s and 1980s, representing victims of brutality. Growing up with her guards-officer father away fighting had instilled an early fascination for the war hero, culminating in her masked Greek-warrior ‘Riace’ figures of the 1980s; ‘the mixture of both [strength and vulnerability] that I find in the male figure is very important to me as an idea’.

Other artists and writers with whom parallels can be drawn are Louise Bourgeois, Eduardo Paolozzi, Günter Grass and F. G. Lorca. There is no doubting the significant contribution Frink made to European post-war art, yet, within a British context, she has been described as ‘falling between two stools’, not quite part of the older Geometry of Fear group (Armitage, Chadwick, Butler, Meadows), yet neither belonging to the new generation of Abstract sculptors such as Caro and King, although she absorbed elements of 1960s Pop culture.

Frink mixed with the likes of Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and George Melly and was a vibrant, popular figure on the 1950s and 1960s London bohemian scene. Bacon, in particular, shared a friendship and artistic affinity with the strong, androgenous-looking sculptor, whose Small Head (1959), with jaws agape in a terrifying scream, recalls his biomorphic creatures. Her ‘Goggle Heads’, which she made after moving to France with her second husband in 1967 and are among her most arresting works, exude a Bacon-like malevolence and brutality.

It was not all existentialist angst, however. Frink was interested in the heroism and psychological strength of survivors of persecution and works such as her ‘Running Man’ series (1976–80) can be seen as symbols of hope. Shortly before her death, she was exploring, in her various media, the theme of the Green Man, with its promise of renewal and rebirth.

Finding Frink

In 1976, Frink moved to Dorset — to Woolland, overlooking the Blackmore Vale — where she lived with her third husband, Alex Csáky, whose son, architect John Csáky, designed a studio for her. Messums Wiltshire recently rescued the studio and reconstructed it at the great tithe barn in Tisbury, where it can be seen, with original plasters, tools, letters, objects, photographs and film, in ‘A Place Apart’ until October 18 (www.messumswiltshire.com).

Before he died in 2017, Frink’s son, Lin Jammet, requested that her collection of about 900 works, which Annette Ratuszniak has catalogued, as well as her archive of photographs and documents, be given to the nation. The bequest has been divided between 11 museums and galleries; the archive (part of the National Archives) housed with the Dorset History Centre in Dorchester, where the County Museum is creating a dedicated Frink gallery.

More than 100 paintings and other artworks that belonged to Frink will be auctioned by Woolley & Wallis, Salisbury, on August 26. ‘Elisabeth Frink. Man is an Animal’ will be at Gerhard Marcks Haus, Bremen, November 1–March 7, 2021, and at Museum Beelden aan Zee, The Hague, March 21–June 6, 2021. Beaux Arts London will stage a solo exhibition in March 2021.

Books on Elisabeth Frink

Frink: A Portrait by Edward Lucie-Smith and Frink (1994); The Official Biography of Elisabeth Frink by Stephen Gardiner (1998); Elisabeth Frink: Catalogue Raisonné of Sculpture 1947–93 edited by Annette Ratuszniak (2013); Elisabeth Frink: The Presence of Sculpture by Annette Ratusniak (2016); Humans And Other Animals by Calvin Winner (2018)

Credit: James Wild / hgbphotos

In Focus: A sculptor creating 21st century art from the detritus of 20th century life

You're more likely to find artist James Wild hunting through a scrapyard than to find him among the normal haunts

In Focus: The sculptor whose work 'treads that fine line between likeness and caricature'

At a time when public statuary is much in the news, Timothy Mowl considers the work of a leading British

In Focus: Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, the Scottish artist whose work spanned the 20th century

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004) spanned the 20th century with a remarkable range of figurative and abstract paintings and drawings that deserve

Mary Miers is a hugely experienced writer on art and architecture, and a former Fine Arts Editor of Country Life. Mary joined the team after running Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. She lived in 15 different homes across several countries while she was growing up, and for a while commuted to London from Scotland each week. She is also the author of seven books.

-

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of them

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of themThe Arts and Crafts movement was an international design trend with roots in the UK — and lots of buildings built and decorated in the style have since been turned into hotels.

By Ben West

-

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in Kent

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in KentGrade I-listed Holwood House sits in 40 acres of private parkland just 15 miles from central London. It is spectacular.

By Penny Churchill