In Focus: The six ‘poems in paint’ by Titian that are in the same room for the first time in 500 years

Michael Prodger heralds the ‘Titian: Love, Desire, Death’ exhibition at the National Gallery, a once-in-a-lifetime collection of a group of paintings he calls ‘one of the highpoints of Western art’.

NOTE: Michael Prodger visited the National Gallery before it was closed due to coronavirus (it will remain closed until at least May 4). The Titian exhibition he writes about here was originally expected to run until June 14, after which it was due to move to the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh from mid-July. It remains to be seen if, how and when those plans will change, but you can find out the latest at www.nationalgallery.org.uk. In the meantime, the book of the exhibition, written by Matthias Wivel, is published at £25.

Tiziano Vecellio — Titian — was, with Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael, one of the cluster of men who took Renaissance art to unprecedented heights. Each, however, did so in a slightly different way: Leonardo through uniting art and science; Michelangelo through the heroism of the human body; Raphael through stately grandeur.

Titian (about 1490–1576) came from a different tradition to the others: as central Italians, they gave precedence to disegno — drawing and the intellect behind the design — whereas Titian came from Venice where colorito — colour and painterliness — were more prized. When this background coincided with subjects that fitted his sensibility, he was one of art’s greatest sensualists — and one who is celebrated this year in an exhibition at the National Gallery, called ‘Titian: Love, Desire, Death’.

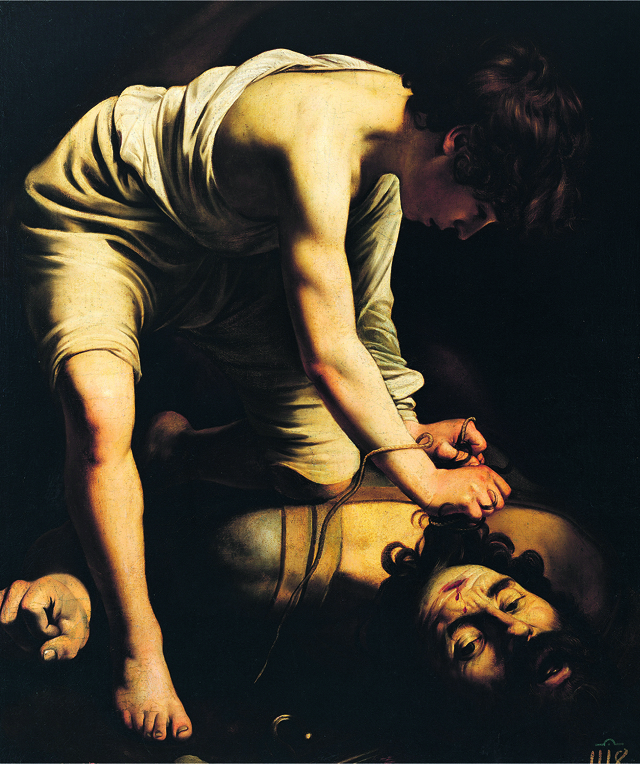

Nowhere was Titian more sensual and nowhere were his gifts for rich colour and equally rich storytelling more evident than in the six paintings based on mythological stories from the Roman poet Ovid he made for Philip II of Spain between 1551 and 1562. Known as the ‘Poesie’ because the pictures were poems in paint as well as in theme, the set quickly came to be seen as one of the highpoints of Western art.

Over the centuries, these prized works were dispersed by sale, gift or wartime appropriation and have ended up split between Spain, Britain and America. Now, almost miraculously, they have been reunited in a one-room exhibition — the first time that they have all hung together since the late 16th century.

The original cycle comprises Danaë (1551–53, from Apsley House); Venus and Adonis (1554, the Prado, Madrid); Perseus and Andromeda (1554–56, the Wallace Collection), Diana and Actaeon (1556–59) and Diana and Callisto (1556–59, jointly owned by the National Gallery and the National Galleries of Scotland); and The Rape of Europa (1562, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston). They are joined in the show by the National Gallery’s Death of Actaeon (1559–75), which was conceived as part of the series, but never delivered; indeed, so rough and vigorous is the handling that there is debate as to whether it is even finished.

What the paintings show is that love and desire lead at best to drama and at worst to danger, indeed death — especially when the gods are involved. They show, too, Titian’s visual inventiveness. Danaë, for example, tells the story of the daughter of the King of Argos, who, when warned of a prophesy that he would be slain by his own grandson, locked her in a tower. This was no defence against Jupiter’s lust and the god had his way with her by metamorphosing into a ‘golden shower through which she was deceived’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Titian took Ovid’s briefest of descriptions and spun it into an erotic masterpiece. His Danaë lies curvaceous and naked on a bed, legs suggestively open as the god tumbles down as a rain of gold coins, eagerly collected by the princess’s elderly servant. Philip II’s reaction to this unashamedly sexual imagining is unrecorded; centuries later, however, the prissy Mark Twain was unimpressed, declaring the painting ‘the foulest, the vilest, the obscenest picture the world possesses’.

For drama of action, The Rape of Europa (pictured, top) shows the abduction of the maiden by Zeus, this time in the shape of a bull who bears her away across the sea to Crete. The terrified Europa clings on to the bull’s horns and waves and drapery surge as the animal swims into the sunset, putti chasing the pair helter-skelter. The picture is all colour, movement and tension as the girl casts her gaze back to her friends left helplessly on the beach.

For psychological drama, Diana and Actaeon depicts the moment the young hunter stumbles inadvertently on the goddess Diana and her maidens bathing in a stream. He has seen her naked, so the encounter will lead to his death (Diana turns him into a stag and he is torn apart by his own hounds). The painting is marked by Actaeon’s shock and the goddess’s outrage at being surprised. As he throws up his hand, she throws on a covering while fixing him with a fatally thunderous look and the tragedy starts to unfold.

There is also a competitive aspect to the ‘Poesie’: here are figures shown naked and clothed and from the front, back and side, in the way of sculpture; here are emotions stirred, from lust to fear, as if by poetry; and here are harmonies of colour and form that swell like music. What Titian was saying here, to Philip II and his own peers as well as to us viewers, was: look, in the hands of an artist of genius, there is nothing painting cannot do.

‘Titian: Love, Desire, Death’ is scheduled to run at the National Gallery, London WC2, until June 14 (www.nationalgallery.org.uk) and at the Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, July 11–September 27 (www.nationalgalleries.org). Both galleries are currently closed due to Covid-19, so please check websites for latest information on dates. The exhibition is accompanied by the book ‘Titian Love, Desire, Death’ by Matthias Wivel and 12 others (National Gallery Publishing, £25).

My favourite painting: Martin Gilbert

'William Dyce is arguably one of the greatest painters to come out of Scotland and certainly the greatest out of

My favourite painting: William Agnew

William Agnew chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

My favourite painting: Fiona Bruce

Fiona Bruce chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

In Focus: The gleaming cups made from gold and kingfisher feathers at the heart of a great British collection

When Richard Wallace, the illegitimate son of a Marquess unexpectedly inherited his father's art collection, he did himself and his

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson