In Focus: The oldest known map of the cosmos, and the detectorists who sold an £8m find for just £13,000

A bronze ‘sky disc’, thought to be the world’s oldest map of the cosmos, is the star attraction of the British Museum's 'The World of Stonehenge' exhibition. Vicky Liddell takes a look.

One of the earth’s most strange and beautiful objects is on display at the British Museum for the first time. Named after the East German town of Nebra, close to where it was unearthed, the Nebra sky disc is estimated to be 3,600 years old and is believed to be the world’s oldest surviving map of the cosmos.

Hewn from bronze that has developed a striking blue-green patina, the disc, nearly 12in in diameter, is emblazoned with inlaid gold symbols representing the sun or full moon, a crescent moon, the solstices and a cluster of stars. ‘Seen up close, the colours are amazing and it’s much bigger than I imagined — about the size of a dinner plate,’ enthuses Neil Wilkin, curator of ‘The World of Stonehenge’ exhibition.

‘The gold is as lustrous as the day it was buried, but the bronze would have been originally artificially darkened to an aubergine colour to represent the night sky.’

The Nebra sky disc is thought to have been used as a portable instrument for the measurement and calculation of celestial bodies. The inlaid gold sheeting depicts different compositions that allow experts to decipher four different phases over its history, the first of which showed the night sky studded with 32 gold stars.

These include a group of seven dots understood to represent the constellation of the Pleiades, the disappearance of which in March and reappearance in October helped prehistoric communities predict the best times for sowing and harvesting.

"It was unearthed by metal detectorists operating illegally who damaged it with their spade and sold the entire find for £13,300... It's since been valued at£8.3 million"

‘In a sky with no light pollution, these stars would have been very obvious to Bronze Age farmers,’ notes Dr Wilkin. ‘They had a sophisticated knowledge of the heavens and could use this knowledge to their advantage.’ It may also have served as a reminder of when it was necessary to synchronise the lunar and solar year by inserting a leap month — a phenomenon that occurred when a 3½-day-old moon (the crescent moon here) was visible at the same time as the Pleiades constellation.

Later, two arcs — one of which was subsequently removed — made from a different type of gold were added to the sides of the disc. Spanning an angle of 82˚, the arcs indicated the angle at sunset between the positions of the summer and winter solstices at the exact latitude for Mittelberg, a hill near Nebra. ‘The astronomical rules depicted are the results of decades of intense observation,’ says Harald Meller, director of the State Museum for Pre-history in Halle, Germany, where the item is usually held. ‘Until the sky disc was found, no one thought prehistoric people capable of such precise astronomical knowledge.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Some time after the addition of the arcs, a gold sun boat — perhaps representing the journey of the sun — was incorporated, then 39 holes around the edge that may have been used to fix it to a pole or standard. Finally, after at least 200 years of use, the disc was buried in a ceremonial hoard, with two swords, two axes, one chisel and two spiral bracelets.

The story of the discovery of the Nebra disc began in 1999, when it was unearthed by metal detectorists operating illegally who damaged it with their spade. They sold the entire find to a dealer in Cologne for 31,000DM (£13,300). The artefact — since valued at $11 million (£8.3 million) — changed hands several times, until archaeologist Dr Meller acquired it in a police-led sting in Basel.

Initially, many suspected the disc was fake and it has caused academic disagreement about the date of its use. However, it is now widely accepted as Bronze Age, after a piece of birch found in one of the swords dated the hoard to about 1600BC. ‘The disc still holds secrets and research is ongoing into the origin of the metals,’ observes Dr Wilkin.

The Nebra sky disc is on show with other objects from the Bronze Age, such as a 3,000-year-old gold sun pendant found in 2018 on the Shropshire Marches. Together, they will shine a light on the vast interconnected world of Britain, Ireland and mainland Europe that existed at the time. There was much trade, as well as exchange of ideas — some gold on the disc came from the River Carnon in Cornwall, notes Dr Wilkin: ‘The movement of the sun was fundamental to all European people and solar symbols were repeatedly shown on objects, suggesting a single belief system.’

Listed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2013, the disc’s inclusion in London marks its first international loan for 15 years. ‘A key piece at our exhibition, it is, without doubt, one of the most important archaeologi- cal finds from prehistory,’ affirms Dr Wilkin.

‘The World of Stonehenge’, February 17–July 17 — see www.britishmuseum.org for details.

Jason Goodwin: 'What gets lost will be forever lost, whereas pylons, cars and trains may be rendered obsolete'

Jason Goodwin muses on economics, Stonehenge and social media.

Beyond Stonehenge: The lesser-known stone circles of Britain

More likely to be ovals, arcs or ellipses, the origins and purposes of our myriad mysterious and sacred stone circles

Credit: ©Country Life Picture Library

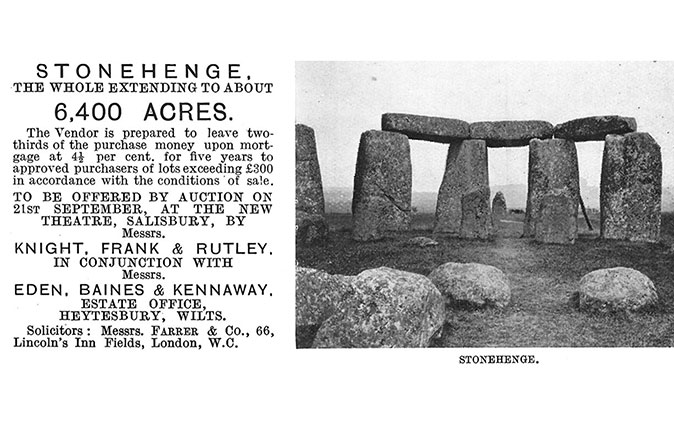

The day that Stonehenge was sold via the pages of Country Life

Stonehenge is shortly to be changed forever, with the planned tunnel getting the go-ahead. But it's not the first time

Vicky Liddell is a nature and countryside journalist from Hampshire who also runs a herb nursery.

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher