In Focus: The Hamilton Aphrodite, 'the finest ancient sculpture ever to have resided in Scotland', and how it smashed its £3 million auction estimate

Huon Mallalieu reports back on the sale of The Hamilton Aphrodite, and a number of other striking pieces which obliterated their estimates.

In 475AD, a fire destroyed much of Constantinople, including the Lauseion, or Palace of Lausus, which contained an unrivalled collection of Greek sculpture. One of the most revered was the Aphrodite of Knidos, sculpted by Praxiteles 800 years earlier, which was one of the earliest Greek representations of the nude female form.

The goddess was posed covering herself with one or both hands as she stepped from a bath. Although the original was destroyed, its renown was such that many copies and variants had been made, ensuring that it has remained the acme of beauty down the ages.

One of the most influential variants is the Capitoline Venus, and one of the best derivatives from that returned to the saleroom at the beginning of December, 73 years after its last appearance on the market. The Hamilton Aphrodite has been described as ‘the finest single piece of ancient sculpture ever to have resided in Scotland’: it was a glory of Hamilton Palace, the vanished Lanarkshire seat of the Dukes of Hamilton, which might itself be described as a Scottish Lauseion, from 1776 to 1919.

This marble goddess, who was a little over 6ft tall excluding her plinth, was essentially a 1st- or 2nd-century Roman version, with 18th-century restorations. Her head was not the original, but was a contemporary Roman fragment and made an admirable fit; indeed, was rather more appealing than that of the Capitoline version. The ears were pierced for rings — in antiquity, such sculptures would be adorned and painted.

In the early 1770s, Douglas, 8th Duke of Hamilton took an extended grand tour accompanied not only by his tutor and physician, Dr John Moore, but the latter’s son, the future Lt-Gen Sir John, hero of Corunna, at whose funeral, famously, not a drum was heard.

The three were painted together in Rome by Gavin Hamilton, a neo-Classical artist, but here working very much in Batoni’s manner. This Hamilton was not related to the Duke, but had been born in Lanarkshire.

He was also one of the leading dealers in Roman antiquities, undertaking excavations at Hadrian’s Villa, where he discovered the Warwick Vase, and it was from him that the Duke acquired his goddess. Writing to Lord Shelburne, a major client, Hamilton reported that ‘the large Venus I had in my possession is now on its way to Scotland. The Duke of Hamilton fell in love with it the moment he saw it, and secured it immediately. It is a fine thing’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Extravagance, including their vast palace, eventually forced succeeding dukes to sell many of their collections in 1882 and 1919 and Hamilton Palace was demolished in the 1920s. William Randolph Hearst owned the sculpture for 20 years, after which it went to a leading dealer and then to the still-anonymous collection from which it has now re-emerged. Sotheby’s gave it its own session with an estimate to £3 million.

After 20 minutes bidding, it was knocked down to an Asian collector at £18,582,000, so the goddess now travels to her third continent.

That sale had been preceded by a mixed-property auction of ancient sculpture, almost half of which came from one collection principally devoted to South Arabian figures. This was a natural field for Antonin (Tony) Besse (1927–2016) and his wife, Christiane, who died last year

His father had made a fortune in a business based in Aden, which Tony took over in 1949, after running arms to the French resistance and working as an illegal taxi driver in New York. Although he had been expelled from school, he also inherited his father’s passion for education. Where Sir Antonin had founded St Anthony’s College, Oxford, the son funded Atlantic College in Wales

Many of the South Arabian pieces went well above estimate, the most spectacular example being an 18in-high alabaster figure of a standing woman, loosely dated between the 3rd century BC and 1st century AD. Estimated to £22,000, it made £499,000.

A 7¼in-high alabaster head of a man given the same date span made a 10-times estimate of £40,320.

What happened next to the 33-room ducal mansion being auctioned off for £200,000

This grand country house just outside Monmouth has an incredible history, unbeatable grandeur and a mind-boggling amount of work to

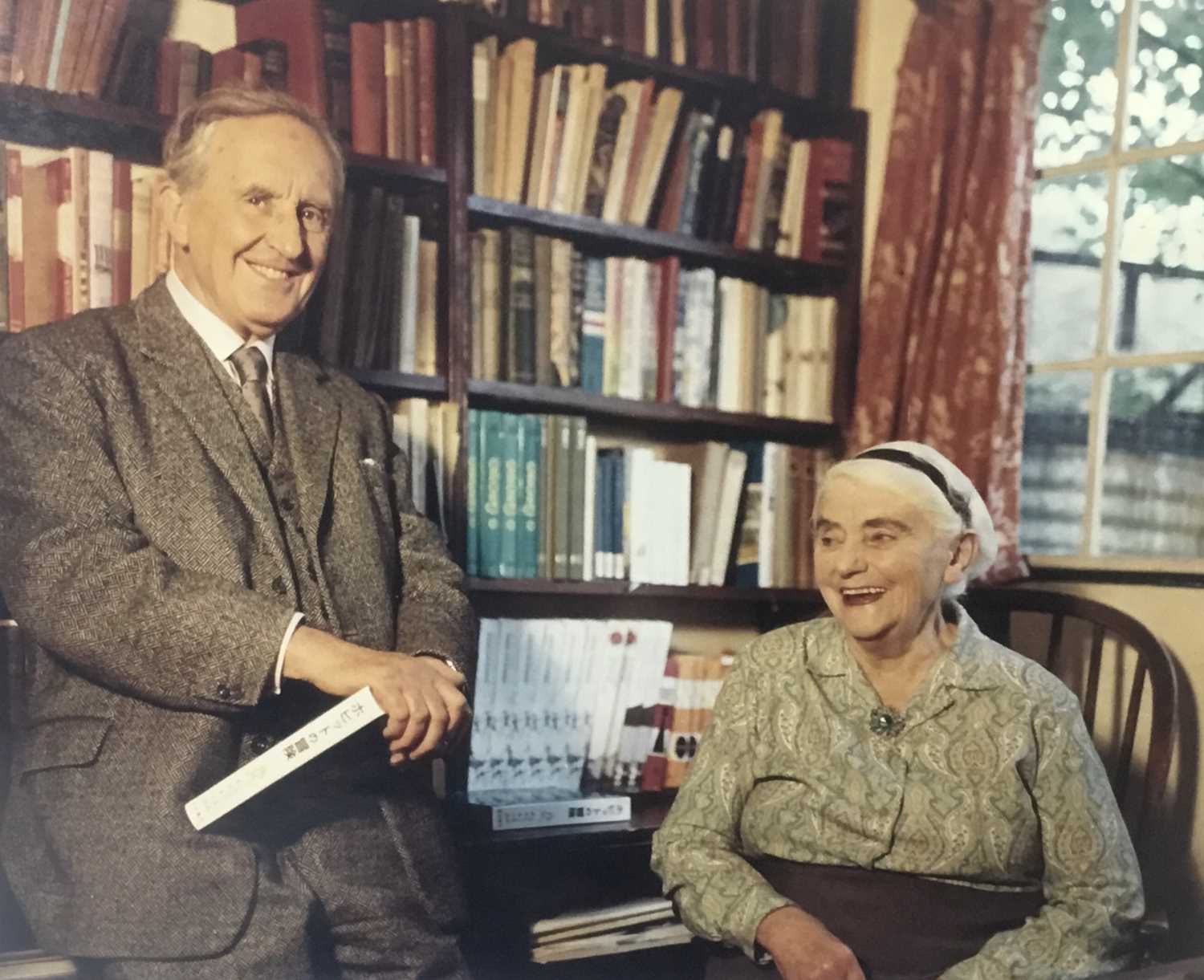

The rare images of J.R.R. Tolkien which caused a sensation at auction

Pamela Chandler's portraits of the great J.R.R. Tolkien went under the hammer recently, almost doubling the estimate set by the

What you need to know about insuring the fine art in your home

Protecting your fine art requires a certain expertise, advises insurance expert Guy Everington of specialist fine-art insurance brokers Castleacre.

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.