In Focus: The copyright lawyer who turned his hand to a 3,000-year-old artform

Jane Wheatley meets Nigel Calvert to discover how glassblowing fulfils him in a way that poring over hundreds of pages of legal fineprint could not.

Glassblowing began with the Phoenicians 3,000 years ago and, according to Nigel Calvert, the process remains essentially the same. ‘It is still hot, physical, risky and painful: scoop up a bit of clear molten glass, melt some green, flow it down over the clear, pick up some white like a pencil you can draw lines with. It’s a fluid medium you can spin and swing, heat and cool, but you have to work reasonably fast; glass has a memory and, after a while, it becomes like a rebellious dog and won’t do what you want.’

We are talking at his home on a high ridge above Stroud, Gloucestershire, looking down over the parkland planting of Nether Lypiatt Manor. Sunlight illuminates a display of his work: heavy glass pieces, sinuously curved, shot through with intense colours: peacock blue, spring-grass green, blood red. There is a jug the exact colour of gazpacho. I want it to serve the iced soup in, but, I note sadly, it would be too heavy to lift.

‘That’s probably true,’ he shrugs. ‘But still I like to make vessels. I always want to create something that has form and prompts desire — “Oh, I want to put something in that”.’

A copyright lawyer by trade, Mr Calvert began glassmaking 25 years ago. ‘Each piece is months in the planning,’ he reveals. ‘I work in chalk on the floor of my studio until the day comes when it’s time to go to the foundry.’

Currently, he is thinking about using basalt pebbles gathered from the foreshore of the River Severn not far away. ‘I like to abstract the form of the natural world into glass,’ he observes.

In Focus: The art that has broken out of London's galleries and made it onto the street

Art is breaking free from the traditional gallery and its emergence on our streets and in our parks is changing

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In Focus: The extraordinary William Morris, the man for whom the word polymath was coined

Famous for urging us to have nothing in our homes that is not useful or beautiful, William Morris’s masterful command

In Focus: The mesmerising work of Anni Albers, the Bauhaus graduate who turned weaving into fine art

Anni Albers' extraordinary talent for weaving elevated her craft to the very highest levels. Chloe-Jane Good takes a look at

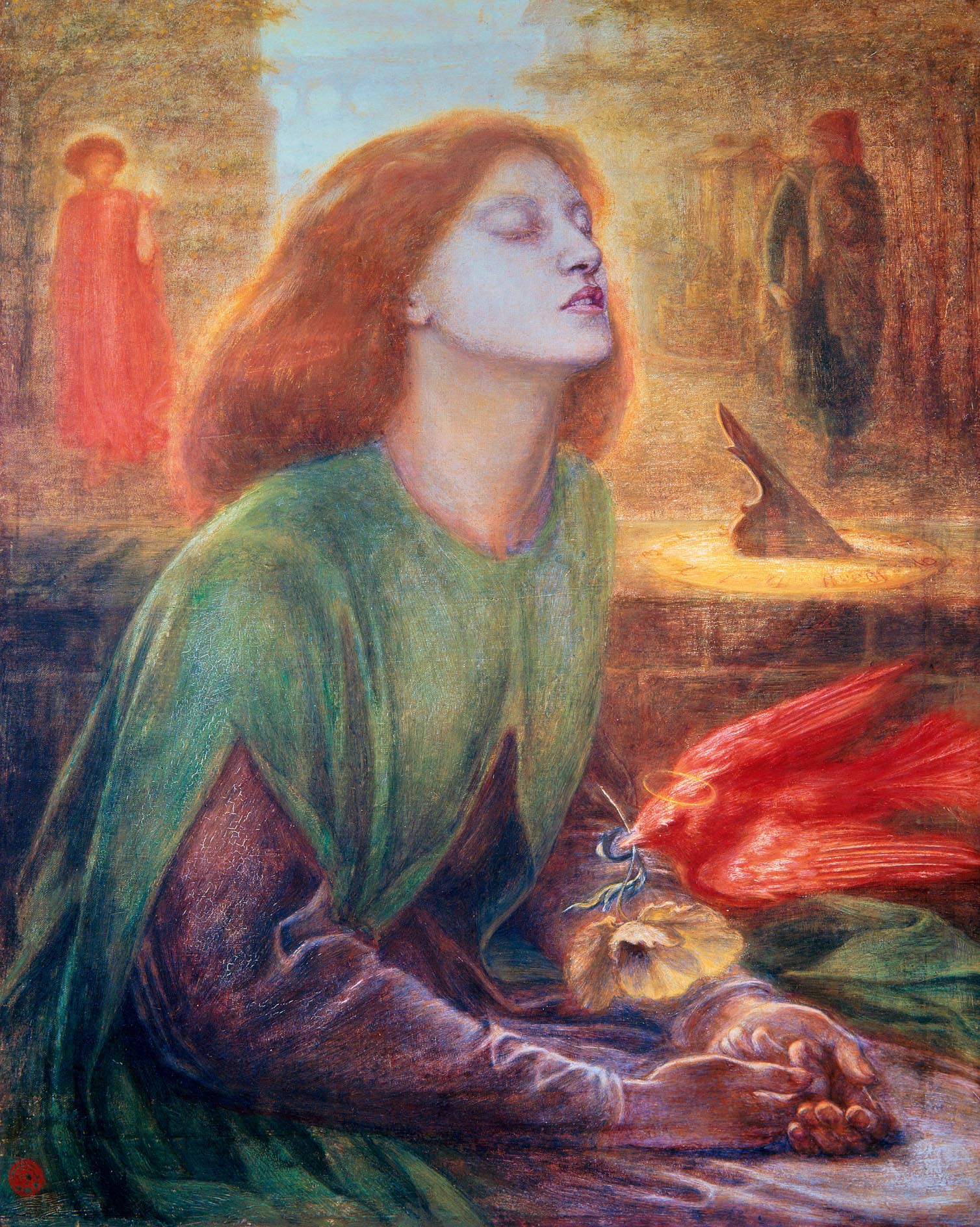

In Focus: The strangely successful career of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the artist 'whose influence was far greater than his output warranted'

He may not have been the most talented member of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, but Dante Gabriel Rossetti was easily the

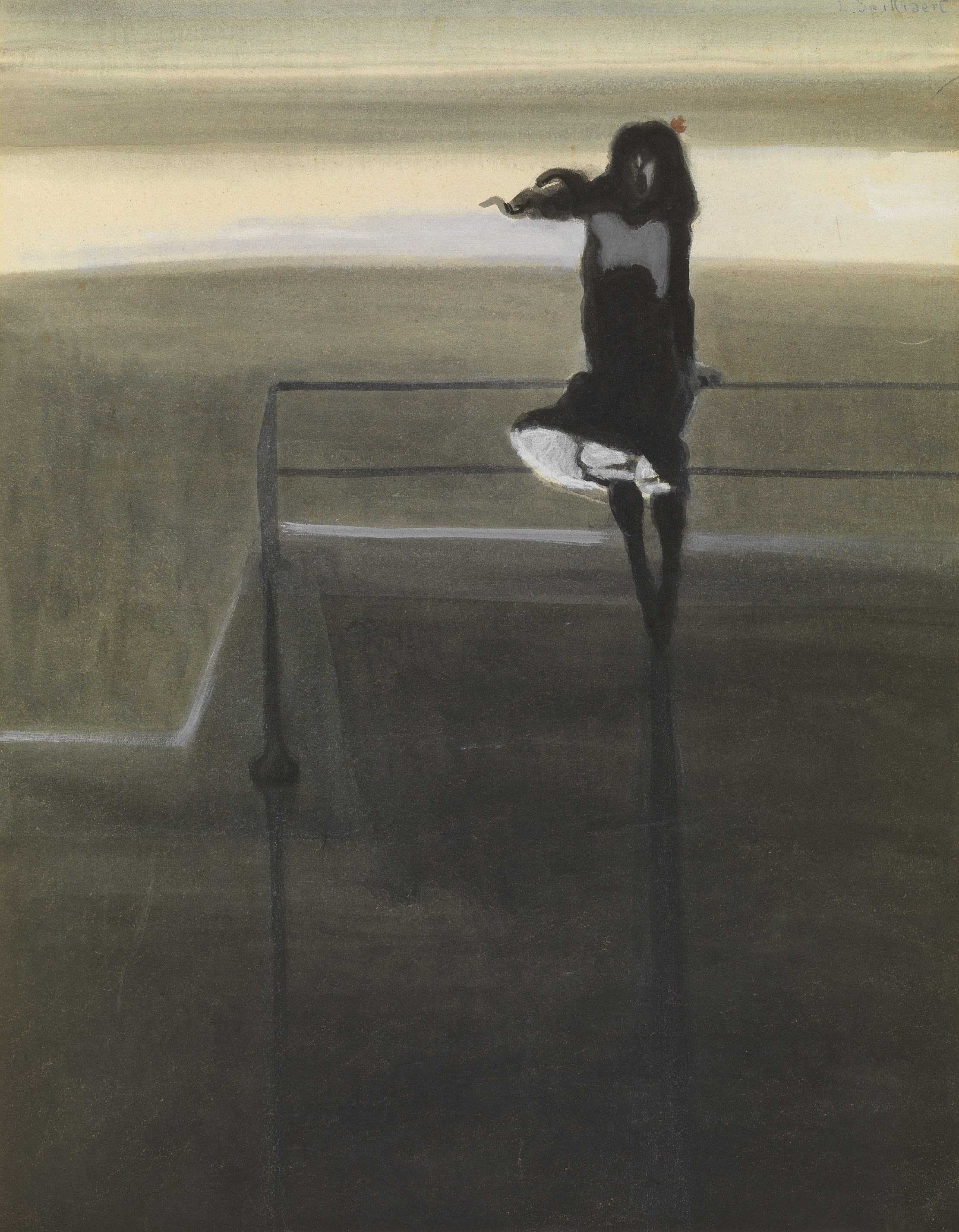

In Focus: The genius of Léon Spilliaert — 'If a ghost could paint, this is what it might look like'

Laura Gascoigne is enthralled by The Royal Academy's exhibition — available in virtual form on their website — focusing on Léon Spilliaert,

Jane Wheatley is a former staff editor and writer at The Times. She contributes to Country Life and The Sydney Morning Herald among other publications.