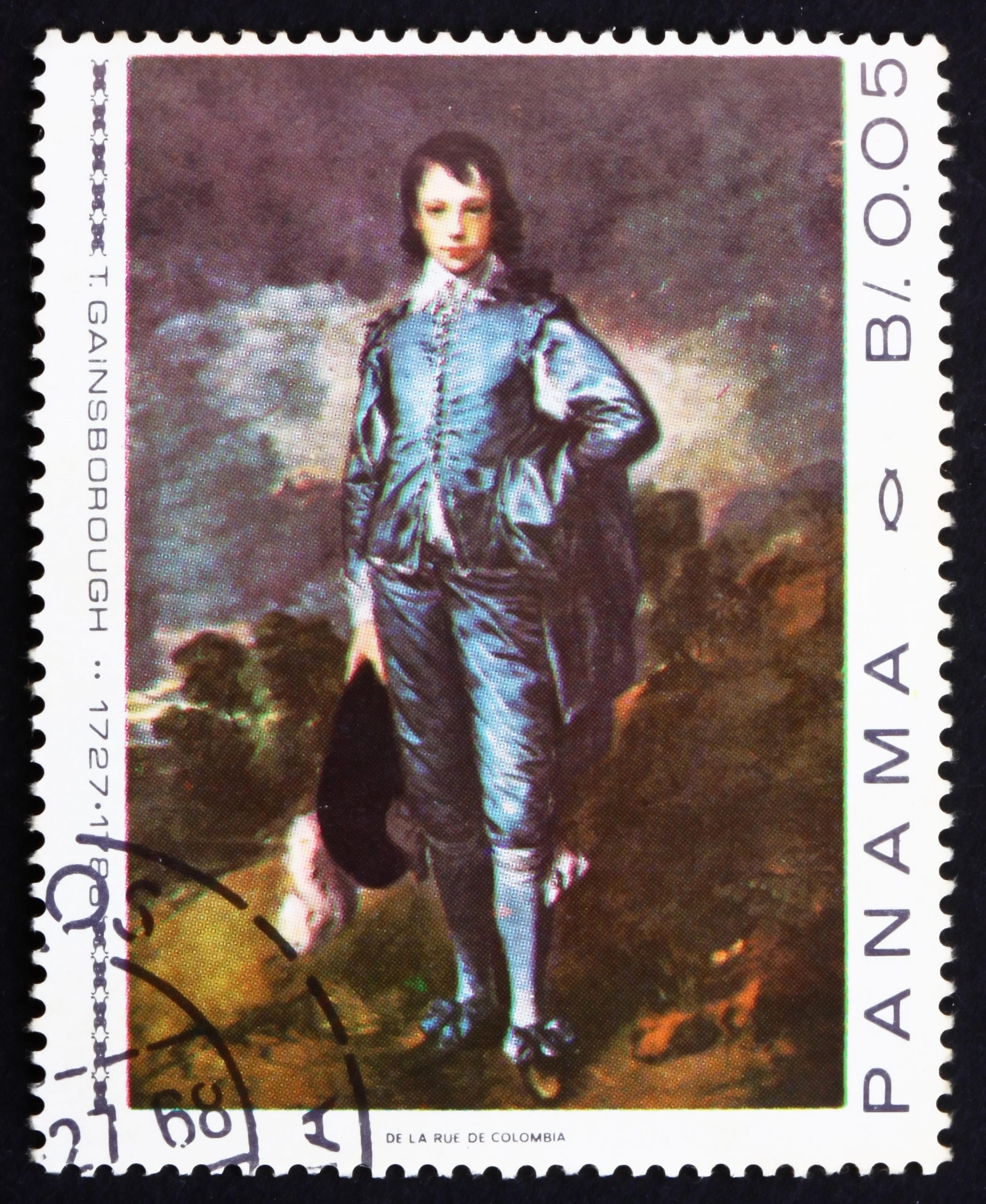

In Focus: The Blue Boy's return to London for the first time in a century, and what it tells us about the state of art

The Blue Boy is back, a century after becoming the most expensive painting in history. Our arts columnist takes a look.

On Tuesday — exactly a century after it was last seen on public display in Britain on January 25, 1922 — The Blue Boy by Thomas Gainsborough returned on loan from the Huntington Art Museum, in San Marino, California, to the walls of the National Gallery, London.

It’s the first time it has travelled since 1922 and will remain on display here as part of a free exhibition until May 15. Athena would warmly encourage her readers to take advantage of the opportunity and that’s not only because this is a magnificent painting.

A Portrait of a Young Gentleman, as it was entitled when first exhibited to acclaim in the Royal Academy exhibition of 1770, is an artistic essay in the manner of Anthony Van Dyck (1599–1641), a defining figure in the tradition of British portraiture. It shows a full-length portrait of a boy — his identity is not known — staring straight out of the canvas at the viewer.

His 17th-century costume of rippling blue silk won the painting its familiar modern name by 1798. The boy stands against a dark background, with one hand placed confidently on his hip and the other holding a plumed hat. A shaft of light from high above illuminates his face, emphasising his ruddy cheeks and ruby lips.

This striking portrait grew steadily in celebrity over the 19th century and was loaned widely by the Duke of Westminster including, in 1908, to an exhibition of the best English art displayed in the Berlin Royal Academy to promote Anglo-German understanding. The status and celebrity it enjoyed were further illustrated in 1921 when the American railway magnate, Henry E. Huntington (1850–1927) purchased The Blue Boy for $728,000 — equivalent to around $11 million (or £8 million) adjusted for inflation. It was then the largest sum ever paid for a painting.

In a three-week valedictory exhibition at the National Gallery, 90,000 people travelled to see it. As the canvas was packed up, the director, hopeful that it would one day return, wrote ‘Au revoir’ in pencil on the back. And now it has.

The irony of all this is that, for all its former celebrity as an icon of Englishness, The Blue Boy returns home in 2022 with vastly reduced popular recognition. Nor, Athena would venture, will it be easy for a modern viewer to see reflected in it much that they could identify with as English. We can enjoy this superb painting, in other words, but the idea of it as a mirror to our history and identity simply doesn’t ring true any more.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

There are other works of art whose historic celebrity must mystify the modern viewer in much the same way; the Pre-Raphaelite Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World (1853) springs to mind. They challenge us to understand what previous generations saw in them. In the process, they should make us reflect on how puzzling our own cultural fixations might seem in the future.

The Blue Boy is on show at the National Gallery in London until May 15.

Credit: Private collection via the National Portrait Gallery. Photo by Matthew Hollow.

How Country Life helped track down a lost masterpiece by Gainsborough

Five years of fruitless searching had left the National Portrait Gallery almost abandoning hope of finding a lost Gainsborough painting,

Credit: Bridgeman

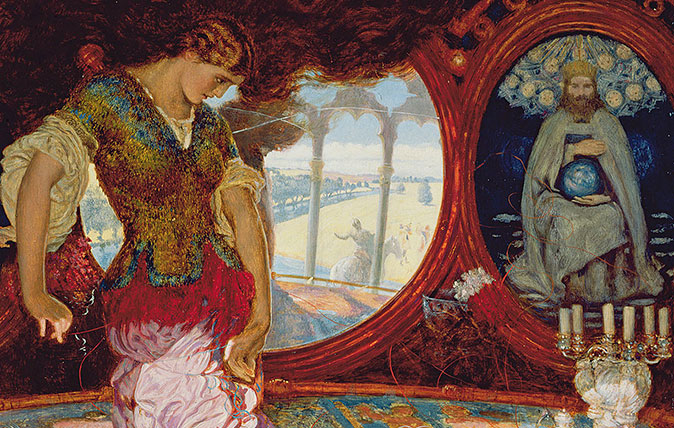

In Focus: How Holman Hunt's Lady of Shallot was inspired by Van Eyck's greatest masterpiece

Holman Hunt was one of several pre-Raphaelites inspired by Jan Van Eyck's iconic The Arnolfini Portrait. Lilias Wigan takes an

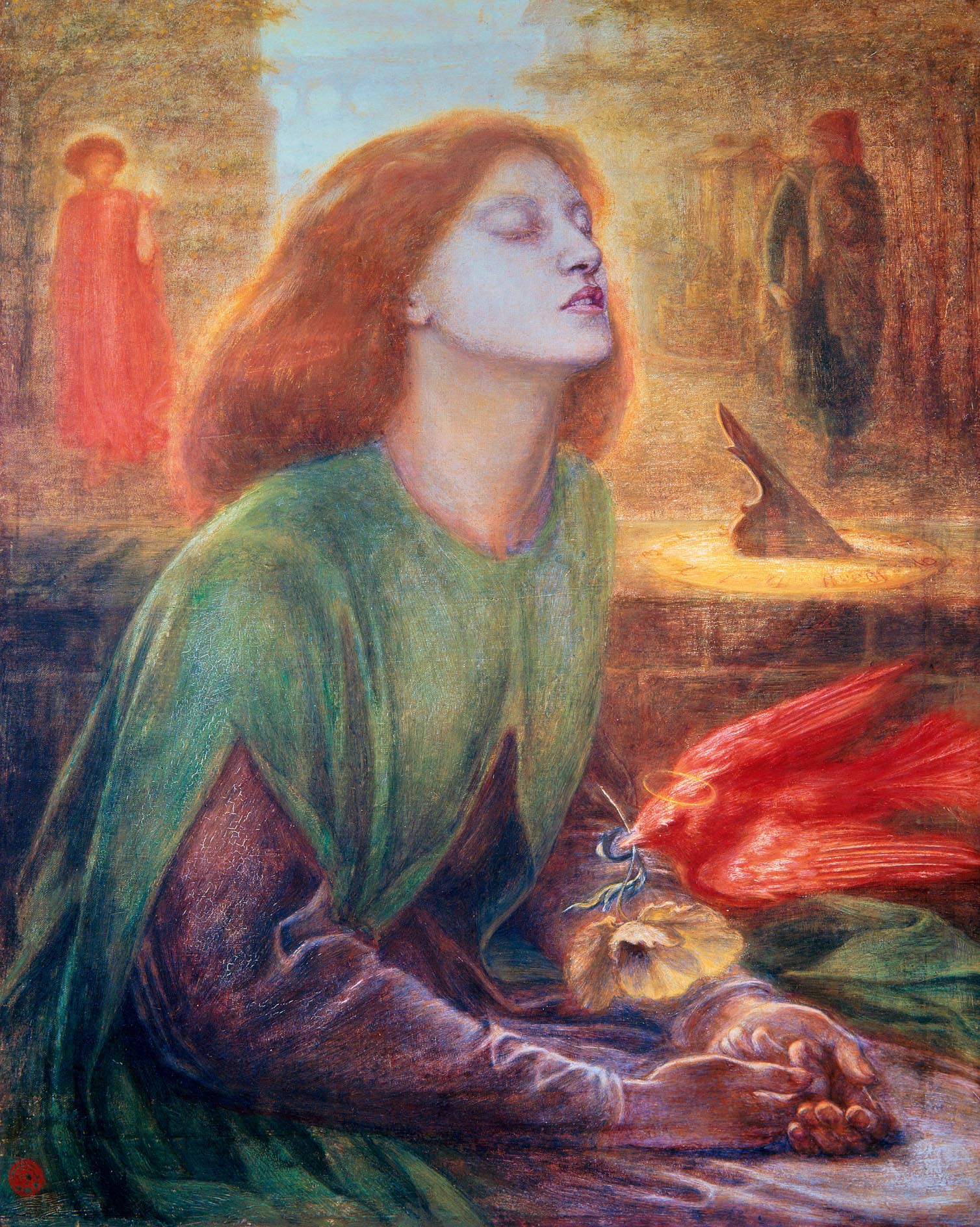

In Focus: The strangely successful career of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the artist 'whose influence was far greater than his output warranted'

He may not have been the most talented member of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, but Dante Gabriel Rossetti was easily the

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producers

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producersStormzy, Rihanna and the Rolling Stones are just a part of the story at Osea Island, a dot on the map in the seas off Essex.

By Lotte Brundle

-

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The Season

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The SeasonHere's how to navigate this summer's top events in style, from those who know best.

By Madeleine Silver