In Focus: The billion-dollar art collection of Microsoft's co-founder, and what happened when it went under the hammer

Huon Mallalieu takes a look at the extraordinary paintings collected by Paul Allen over a lifetime of considered art appreciation.

Paul Gardner Allen (1953–2018) appears to have been a billionaire who would have actually been interesting to meet. Technological masters of the universe may be riveting to read about, but, often, they do not give the impression of being much fun socially. Away from the screen, Steve Jobs collected shin-hanga, modern Japanese woodcuts, and Elon Musk is reported to be interested in another Japanese art form, ippitsu ryu, whereby dragons are painted in one stroke without lifting brush from paper. Richard Branson collected contemporary African paintings and then sold them for charity, but Allen and Bill Gates, his school friend and partner in creating Microsoft, are less usual in that they became very serious art collectors.

As I have undoubtedly mentioned before, in 1970, I was behind the rostrum when Velázquez’s Portrait of Juan de Pareja was knocked down for £2.2 million, the first work of art of any kind to make more than £1 million at auction, and a thrilling moment it was. That would be equivalent to about £32.7 million today, but, in Allen’s sale last month at Christie’s New York, no fewer than five paintings topped the $100 million (about £83 million) barrier and the average price for the 60 lots was $25 million, bringing a total of $1.5 billion. The following day, 95 more lots of ‘lesser’ works produced a further $115.9 million.

What surprised me — of course it shouldn’t, but who can one look down on if not billionaires? — was the evidence of a strong taste in his collecting. There were a couple of Hirsts in the secondary session, one of them even reaching $1.26 million, but there were few of the wealth signifiers, such as Warhols, that might have been expected. Here, the span was from Botticelli and Brueghel to Hepworth and Hockney.

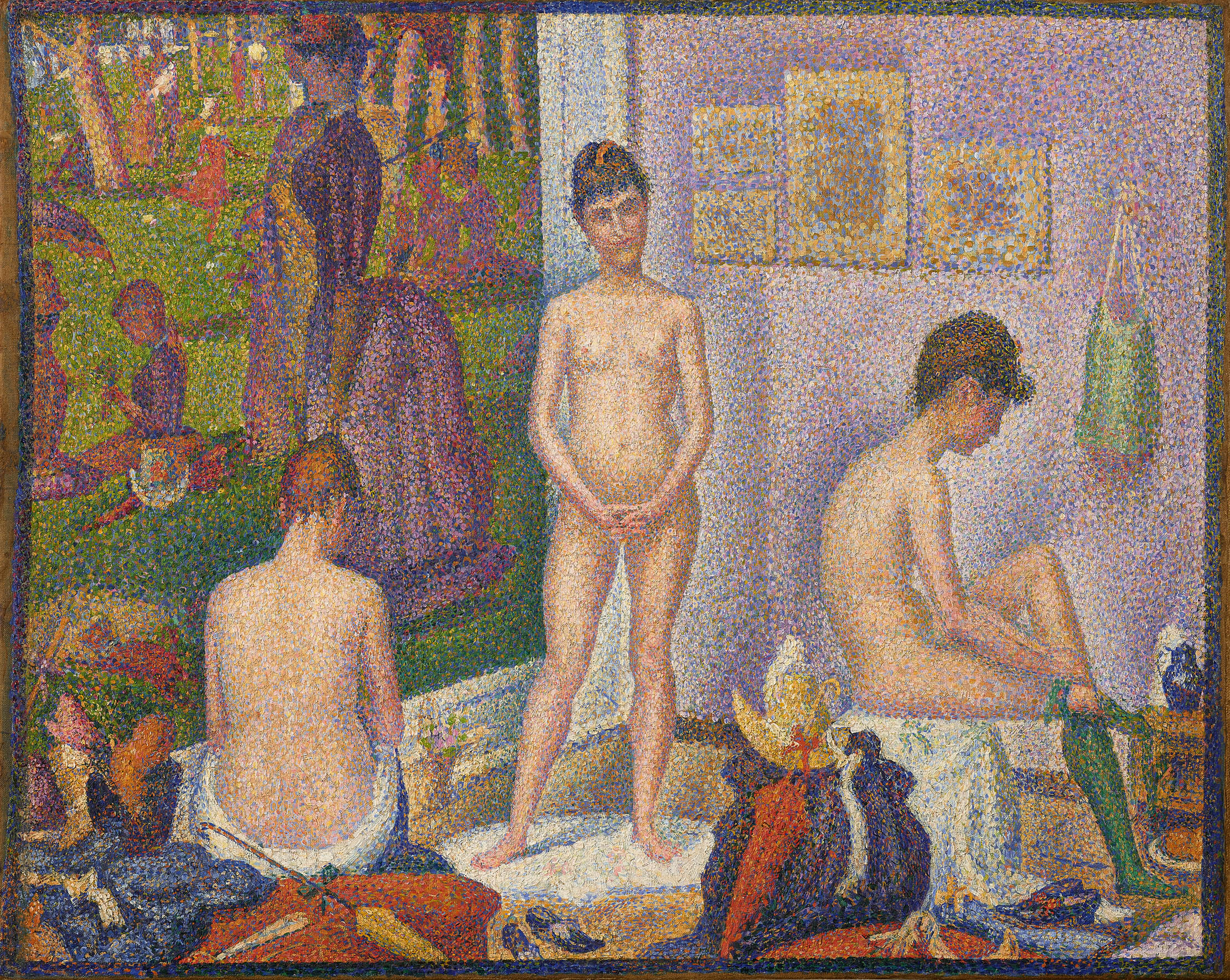

Let us pause for a moment to look at the five $100 million-plus paintings. The first thing to be said about the small (15½in by 19¾in) version of Les Poseuses, Ensemble (Fig 1), which reached $149.24 million, is that it is very beautiful. The title is best translated as ‘Models resting’, the ‘ensemble’ perhaps recognising that this is, in fact, one woman in three poses. Seurat painted the two versions in 1888 as a riposte to critics who had said that the pointillist style of his 1884–86 La Grande Jatte, seen behind the figures in the studio, lacked realism. In the interim, he had developed his theory of divisionism, in which the dots of colour are placed individually, leaving it to the observer’s eye to mix them. This is surely a convincing riposte.

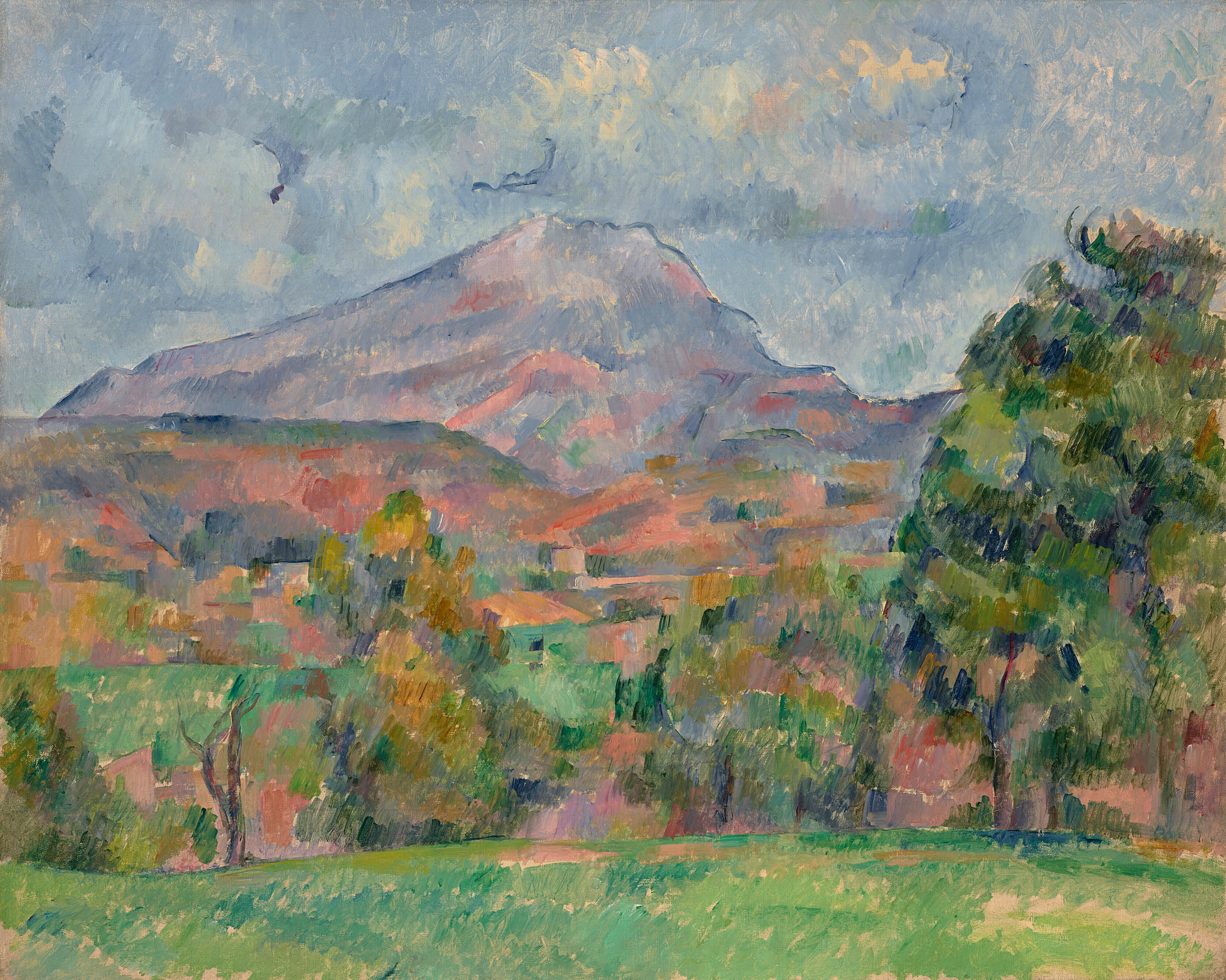

More beauty is to be found in Cézanne’s 25½in by 32in Montagne Sainte-Victoire (Fig 2) painted very shortly after the Seurat. For a few happy months in my youth, I lived in a mas on the then outskirts of Aix-en-Provence with a daily view of the pyramidic flank of the Montagne Sainte-Victoire, which I came to love almost as much as did Cézanne. It perfectly demonstrates how his still lifes are essentially landscapes and his landscapes still lifes. However, the mountain was alive for him, and I also love his exclamation: ‘Look at the Sainte-Victoire there. What élan, what imperious thirst for the sun, and what melancholy in the evening, when all that weight sinks back!’ Allen’s view, one of the many versions, sold for $137.8 million.

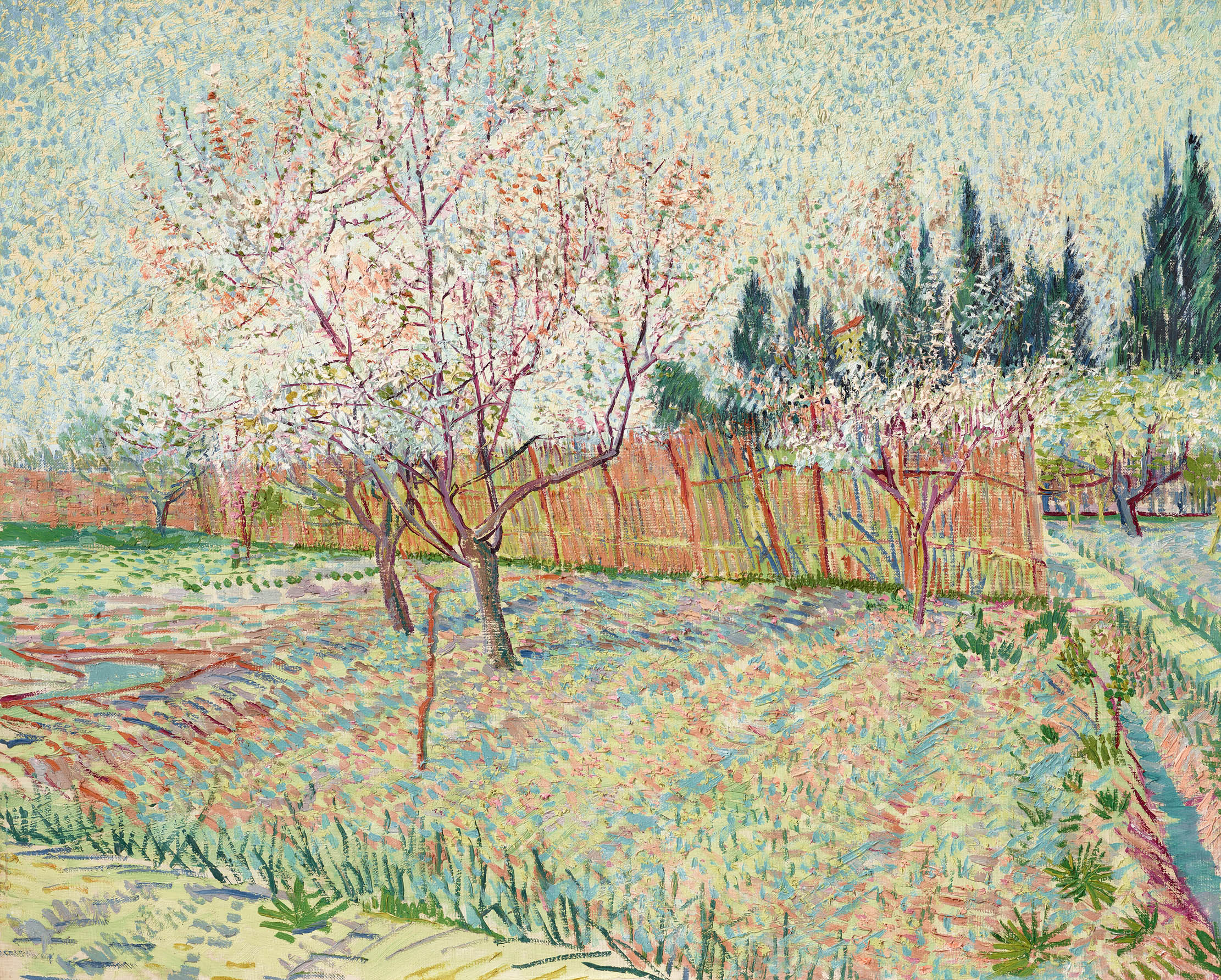

At $117.2 million came van Gogh’s 25¾in by 32in Verger avec cyprès (Fig 3), pleasing, but not perhaps one of his most powerful works. The same might be said of Klimt’s 43½in by 43¼n Birch Forest (Fig 4) of 1903 ($104.6 million), rather Pre-Raphaelite without figures.

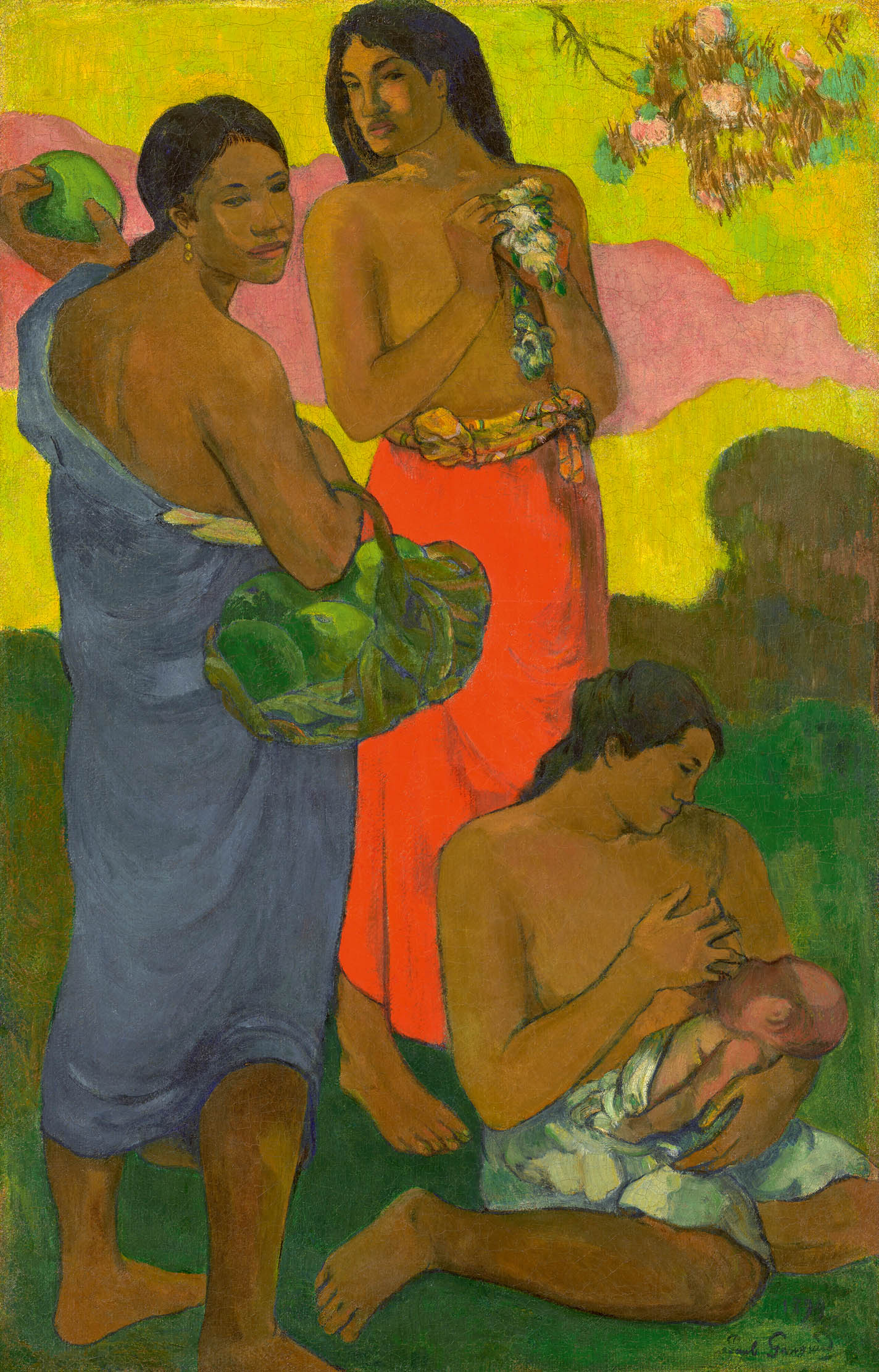

Before automatically condemning Gauguin for living with young teenage girls on Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands, it might be worth considering that, in the 1890s, the populations were in steep decline, life expectancy was 20 to 22 years and early breeding was literally vital to the survival of the people.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Gauguin’s 37¼in by 24in Maternité II (Fig 6) ($105.73 million) was painted in 1899 shortly after Patura, his vahine, had given birth to their son, Emile, and the shape and colouring of the baby’s head points to a personal interpretation, although the whole composition has classical origins. He had only recently lost his caution about the burning South Sea palette and, here, his handling of colour is explosive.

In the secondary session, an untitled creation in stainless steel and lacquer (Fig 5) by Sir Anish Kapoor reached $919,800. It was an 86½in-diameter pleated circle in vibrant, near Yves Klein, blue, which seemed to draw one like a carnivorous flower. Sir Anish’s work does not always work for me, but it is best when experienced in actuality.

Making art from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atom bombs is more ‘challenging’ than many of the works that claim to be so, but glass models of Fat Man & Little Boy are certainly disturbing, perhaps because of their silence and fragility. Here the two — Fat Man measured 20¼in by 20¼in by 33in — from an edition of three, plus an artist’s proof made by Gary Hill in 2014, reached $40,320.

In Focus: A self-portrait by Gaugin which fuses the real and the imaginary in a picture of narcissism and divine comparison

Lilias Wigan analyses Gaugin's 'Christ in the Garden of Olives', commenting on the painter's propensity to focus on himself, understanding

In Focus: The French collection of the extraordinary Wilhelm Hansen, Monet and Manet to 'a wall-full of Pissarros'

Caroline Bugler finds much to enjoy at the Royal Academy’s show of 19th-century French art on loan from Wilhelm Hansen's

In Focus: The artist whose masterpiece was voted Norway's national painting, finally getting the recognition he deserves elsewhere

Caroline Bugler is spellbound by the Scandinavian landscape painter’s magical evocation of fjords, villages and mountains.

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.

-

Burberry, Jess Wheeler and The Courtauld: Everything you need to know about London Craft Week 2025

Burberry, Jess Wheeler and The Courtauld: Everything you need to know about London Craft Week 2025With more than 400 exhibits and events dotted around the capital, and everything from dollshouse's to tutu making, there is something for everyone at the festival, which runs from May 12-18.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Everything you need to know about private jet travel and 10 rules to fly by

Everything you need to know about private jet travel and 10 rules to fly byDespite the monetary and environmental cost, the UK can now claim to be the private jet capital of Europe.

By Simon Mills