In Focus: The art that has broken out of London's galleries and made it onto the street

Art is breaking free from the traditional gallery and its emergence on our streets and in our parks is changing the way we live, says Clive Aslet.

Here’s a tip for anyone wanting to engage bored children as they go around the capital :count the statues. They are thick on the ground — they’re up on plinths, in pediments, on the façade of Fortnum & Mason. In recent years, some have been contested, but neither the number of statues already in situ, nor the opprobrium some excited has deterred developers, public authorities and champions of special causes from adding more.

Look at the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square, occupied by a succession of colourful, if sometimes incomprehensible artworks in recent years. Always the subject of great popular debate, it is only one of the many ways in which public art is transforming London. It can delight and amaze those who see it, contributing to the conviction of many Londoners that they’re living in the best city in the world.

The East End now has a public sculpture trail that links a dozen or so artworks from the Olympic Park to the Millennium Dome. It’s called The Line. Some, such as Richard Wilson’s A Slice of Reality — a section of a sand dredger, cut like a cake and deposited on the foreshore — have been in place since the Millennium, but others are new. Joanna Rajkowska’s The Hatchling of 2019 takes the form of a gigantic blackbird’s egg, from inside which comes the sound of hatching chicks (recorded with an ornithologist’s microphone).

Thomas J. Price unveiled the most recent contribution in 2020, Reaching Out: this 9ft-high bronze of a young black woman on a mobile phone can be found in a public park near Stratford. A deliberately unheroic image, although, from size alone, strangely powerful, it was created in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests to address the under-representation of black people in public sculpture. Even Reaching Out is dwarfed by the scale of works such as Antony Gormley’s Quantum Cloud of 2000 on Greenwich Peninsula, where the form of a human body emerges from a miasma of magnetised nails. At nearly 100ft, it is taller than his Angel of the North.

On July 21, The Line unveiled its latest addition, a bronze sculpture by Tracey Emin. A Moment Without You, with five birds perched above head height, is the British artist’s only public sculpture. Nearby are three former working mills on Three Mills island, on major Thames tributary the River Lea.

The name The Line pays tribute to New York’s famous High Line, an old railway line turned into a linear park. London has yet to make as much of its public art as other cities around the world, such as Barcelona, but the number of sculpture trails is growing; one has been created around Wembley Stadium, with 14 works. They are joined by temporary festivals that transform the façades of famous landmarks using projection techniques.

Having begun in Durham in 2009, the Lumiere Festival is another great example, this year running over four nights from 18-21 November, making the most of the long winter evenings. It is produced by Artichoke, a company dedicated to the creation of ‘extraordinary and ambitious’ public art.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

"Sir Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt have been genially chatting on a bench on New Bond Street since 1995... These men of bronze help humanise the street"

By contrast, the Illuminated River project, completed this April, will last for a decade, lighting nine bridges along more than three miles of the River Thames — the Illuminated River Foundation claims it is the longest public art commission in the world.

The originator of the idea, Hannah Rothschild, is ‘proud that this monumental project promotes London as a creative and innovative city on a global stage. We wanted to celebrate the important role that London’s bridges continue to play as part of the capital’s identity, linking the whole city together.’

Every Christmas, Tate Britain’s sober Classical façade becomes an exuberant light show, in the hands of artists such as Chila Kumari Singh Burman, who is inspired, we’re told, by her family’s ice-cream van and childhood visits to the Blackpool illuminations.

These innovative and literally dazzling artworks have not staled the public appetite for traditional sculpture. In July, Princes William and Harry were both present at the unveiling of Ian Rank-Broadley’s statue of their mother in Kensington Palace’s Sunken Garden.

So far, the public seems not to have warmed to the image, which shows the Princess in a stylish outfit holding the hands of three children, but then it did not initially embrace Martin Jennings’s wonderful 2007 sculpture of Sir John Betjeman clutching his hat as he gazes upwards in St Pancras Station, which it has surely now taken to its heart. The jury remains out on Maggi Hambling’s A Conversation with Oscar Wilde outside St Martin-in-the-Fields, where the head of the poet is seen emerging from a coffin.

War memorials continue to be built, too, despite the many decades that have passed since the end of the Second World War. They seem to have been subject to a process of monument inflation, whereby the Women of the Second World War memorial on Whitehall is as big as the Cenotaph, the national memorial to the Fallen of all wars. On the northern side of Green Park, Liam O’Connor’s Bomber Command Memorial — a sober Greek Doric colonnade in Portland Stone — was unveiled by The Queen in 2012; inside stands a group of seven air crew sculpted by Philip Jackson.

These works continue a tradition of public art that was revived, after the Second World War, by the 1951 Festival of Britain. Sculptures by Henry Moore or Barbara Hepworth relieved the monotony of the monolithic architecture that became the new face of Britain’s cities. Today, developers use public art as a means of giving identity to what otherwise might be amorphous neighbourhoods, a contribution to the goal of place-making that makes residents bond with where they live.

Increasingly, Londoners appreciate the theatre of urban life, provided, for example, by the stalls selling street food and Christmas markets that attract happy crowds. Busking adds to the atmosphere. Sculpture adds its own note to the party, continuing to populate the street after humanity has left. The wartime allies, Sir Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt have been genially chatting on a bench on New Bond Street since Lawrence Holofcener sculpted them in 1995. It is a conversation that never ends. These men of bronze help humanise the street.

In Focus: The incomparable photography of Helmut Newton

Photographer Helmut Newton enjoyed a glittering career that blurred the lines between fashion, photography and art; as his centenary approaches

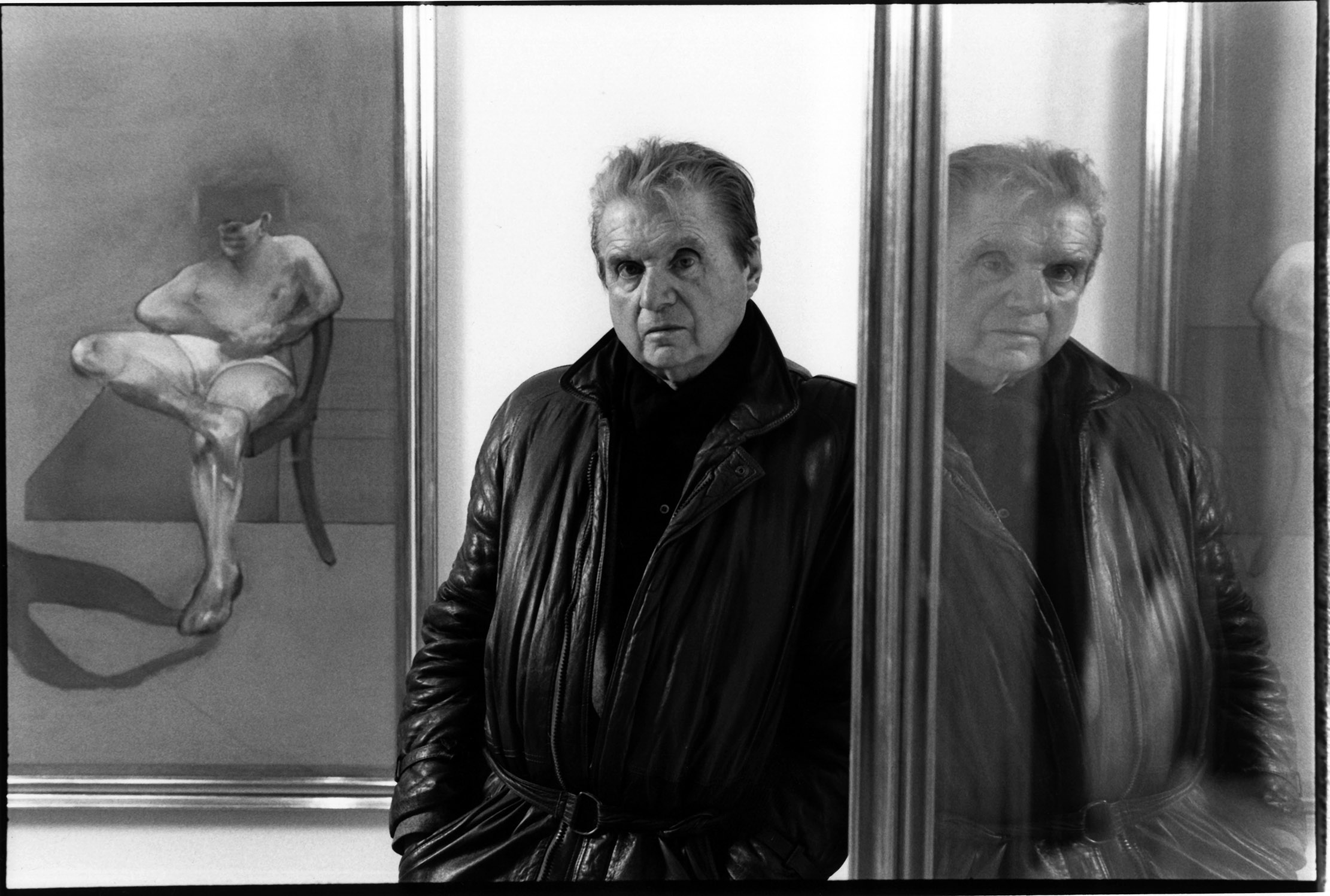

In Focus: The animalistic artworks of Francis Bacon

Martin Gayford considers the importance of snarling creatures, human and otherwise, in the art of Francis Bacon.

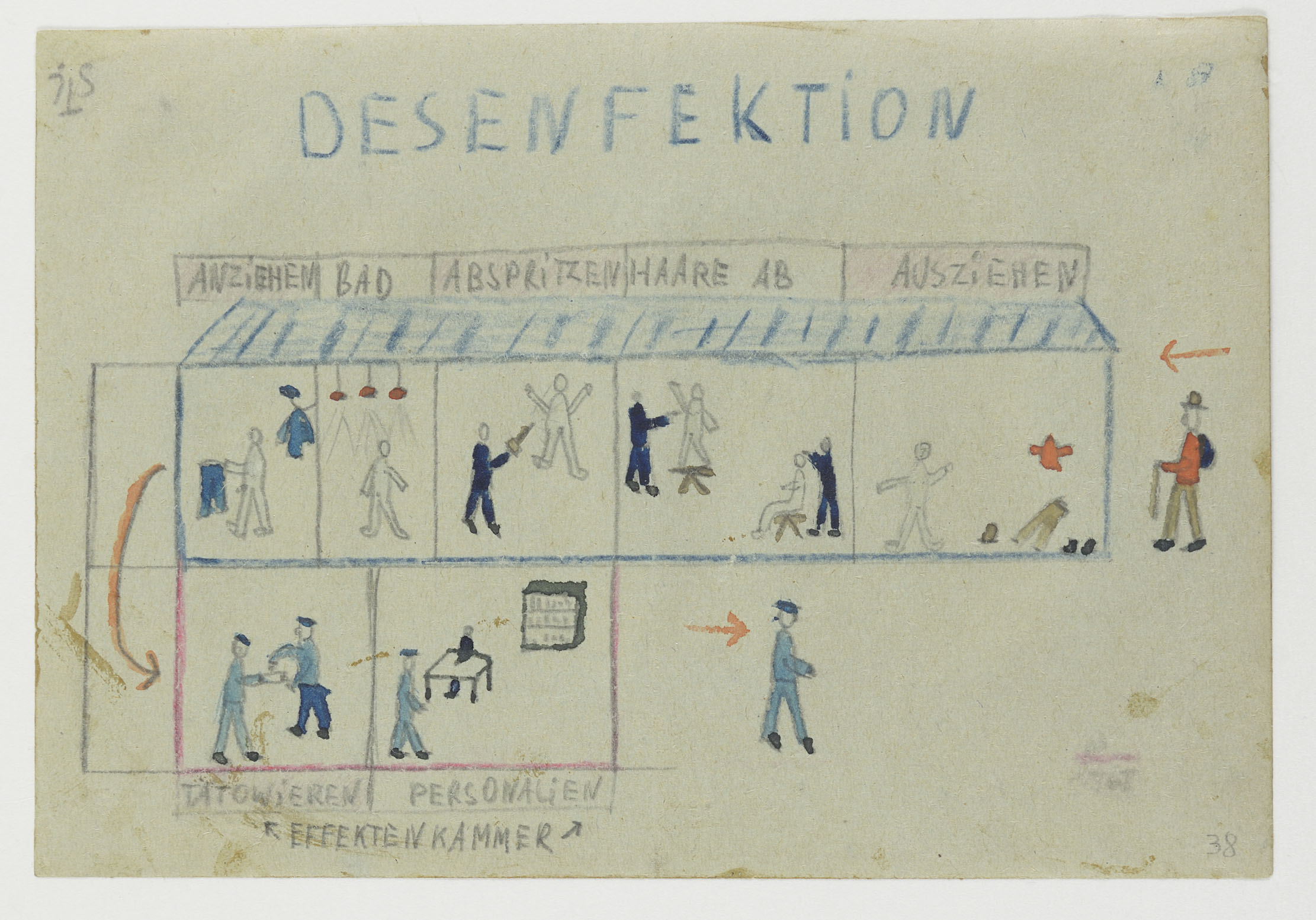

Credit: Thomas Geve via HarperCollins

In Focus: Thomas Geve, the boy who drew Auschwitz

After being liberated from a Nazi death camp, a Jewish boy sketched more than 80 profoundly moving drawings detailing his

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life

-

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire garden

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire gardenDesigners from Sanderson have immersed themselves in The King's garden at Highgrove to create a new collection of fabric and wallpaper which celebrates his long-standing dedication to Nature and biodiversity.

By Arabella Youens

-

Holding pattern: The enduring influence of William Morris on film, fashion and design

Holding pattern: The enduring influence of William Morris on film, fashion and designA new exhibition at Walthamstow’s William Morris Gallery traces the legacy of the Arts & Crafts designer on everything from boots to cinema and even a Japanese waving cat.

By Carla Passino

-

Terrifying or tremendous? Spend a night at the National Gallery beneath some of the world’s most famous artworks

Terrifying or tremendous? Spend a night at the National Gallery beneath some of the world’s most famous artworksBacchus, his girlfriend Ariadne, Fighting Temeraire and a few sunflowers seek roommate for one night only. No smokers or pets. Rent free.

By Rosie Paterson

-

The V&A and Burberry announce landmark Fashion Gallery makeover

The V&A and Burberry announce landmark Fashion Gallery makeoverThe V&A is renovating one of its largest and most-visited spaces — with support from British fashion house Burberry.

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

Anya Hindmarch: 'Luxury can become achingly boring and a bit worthy. I like things that make you smile’

Anya Hindmarch: 'Luxury can become achingly boring and a bit worthy. I like things that make you smile’The thrill of a new pencil case doesn’t fade with age, finds Jo Rodgers, on a visit to Anya Hindmarch’s new stationery pop-up shop.

By Country Life