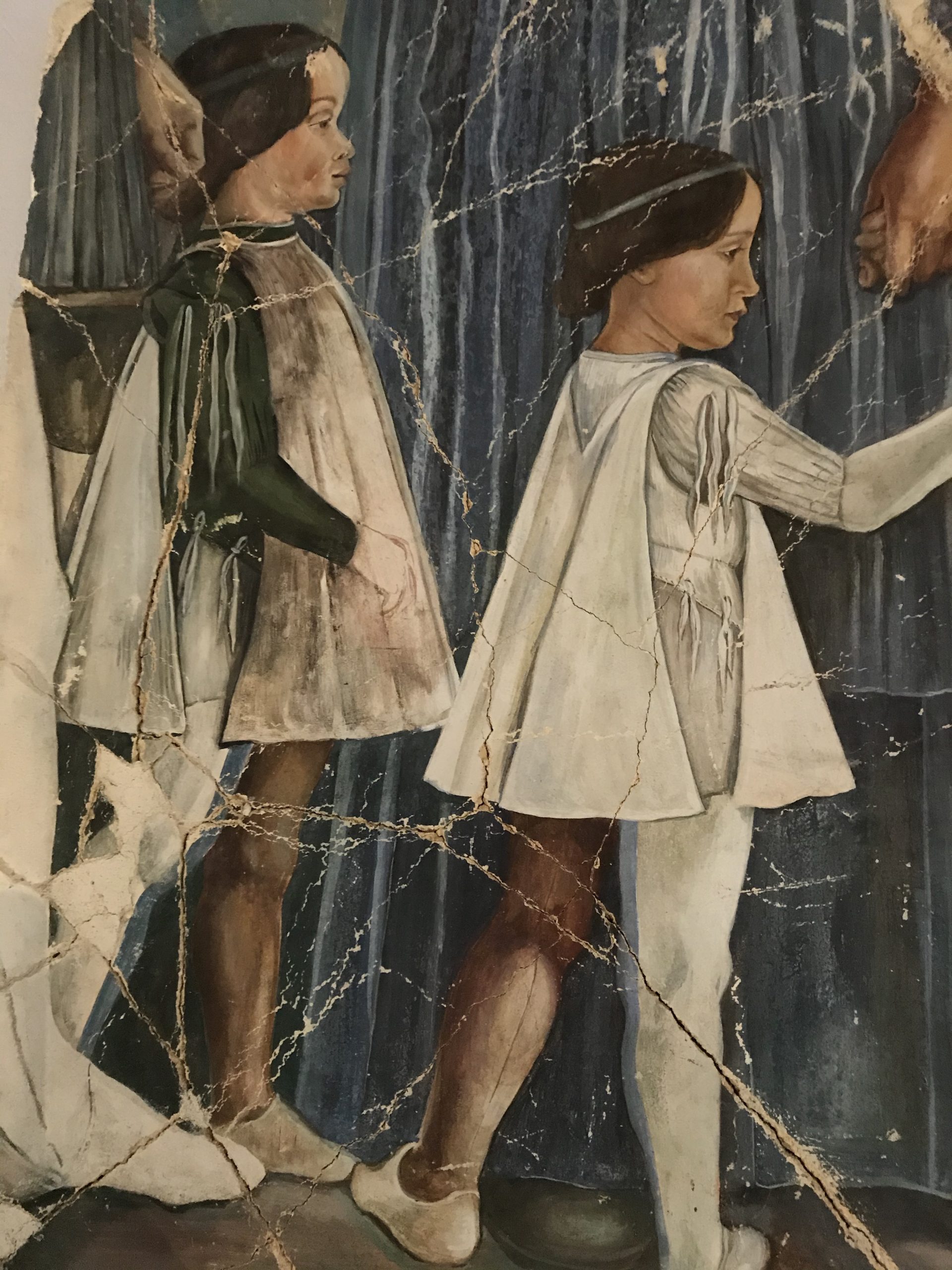

In Focus: How 21st century artists are reviving the art of the fresco

Once practised by Michelangelo, Raphael and da Vinci, the art of fresco creation has changed little in 1,000 years. Marsha O’Mahony meets the artists following in their footsteps.

At the unveiling of the Sistine Chapel’s most famous fresco in 1508, Pope Julius II, who commissioned the work, was rendered speechless. More than 500 years later, Michelangelo’s cornerstone of the High Renaissance continues to inspire awe and wonder. Fresco artists of the 21st century are walking in the footsteps of such masters, creating the illusion of space and time through luminosity of colour and the telling of stories. It remains a potent, if not exclusive, force in art.

Leading fresco artist Fleur Kelly was taught the technique by Leonetto Tintori, one of Italy’s best-known restorers of these works. Her artistic coming of age in 1960s London didn’t bode well for this young woman looking for a different aesthetic, including materials; fresco was certainly not on the curriculum.

After spending several years as a potter and painter, her experience with Tintori changed the course of her life. Today, her commissioned work — including panel and casein (an adhesive and binder, traditionally made with sour milk) painting, both intimate and grand — can be seen gracing Eaton Square sitting rooms, the Tower of London, Oxford Colleges, the Palace of Westminster, churches and Romano-British sites, including St Albans’s Verulamium.

Mrs Kelly’s materials and techniques are little-changed from those of Michelangelo and traditional fresco, painting pigment onto damp lime mortar. The longevity of the fresco is a result of the mortar carbonating with lime, locking in the pigment forever and creating an art form more durable than any other. The tools have scarcely evolved over the centuries: with only a trowel, float and brushes, the artist can be seen most often up scaffolding towers, painting deliberately before the mortar dries.

Before her paintbrush is dipped in pigment, Mrs Kelly will have applied this lime mortar to the surface: the bottom layer, arriccio, and, over this, intonaco, a creamy and velvety finish. She paints onto intonaco when it is still fresh, buon fresco, the pigment eventually held in place by the carbonisation. All of this is achieved through a daily schedule divided into giornata, or sections of fresco, which can be accomplished in a day before the mortar dries. It is a demanding art form.

‘A fresco artist is different to a painter working within a frame. You have to make the whole place work, the room and the ceiling,’ reflects Mrs Kelly. ‘You are often in the public eye as you work, so there is an element of theatre as the space transforms into something else, a great vista opening up. I like to tell a story or to make sense of something and I do a lot of research: what is the building? Where is it? Are people celebrating it?’

When it comes to story-telling, the painter is not averse to inserting some humour into her fresco. She has been known to feature images of clients in their commissions, to good effect: ‘A well-known West End theatre producer commissioned me to work on an architectural folly at his medieval priory home in Somerset. So I painted a pictorial allusion to him and his partner in a Roman setting.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Mrs Kelly has also mentored the next generation of artists, including Cara Campbell, who creates richly detailed botanical frescoes from her Herefordshire studio. Since studying at Tintori’s school, to which she won a scholarship, she has exhibited from London to Melbourne. Her work, combining fresco and stucco, is in several public and private collections. Clients include Swiss art dealer Iwan Wirth, Christopher Gibbs, set designer for the iconic 1960s film Performance, and businessman Bill Ainscough.

Miss Campbell’s attention to the minutiae of fauna and flora suits the secco stage of fresco perfectly, when lime mortar is less damp and the pigments are not ‘sucked’ into the plaster so readily. This calls for a binder.

‘I use egg yolk and water at the secco stage, to help the pigment stick to the mortar,’ she explains. ‘In ancient frescoes, a lot of the detail was done in egg tempera. I like painting Nature from observation, so, for example, using egg tempera on my fresco panels allows me to show each tiny little hair of a dandelion.’

The artist also often combines the technique with heritage plaster work: ‘It always appealed to me and I saw some old pictures of Roman interiors. They’d used stucco, which is the relief work, and frescoes — so I thought, “Why not?”’ She was able to use both for Mr Wirth’s commission in Somerset.

‘Because it was a dining room, I suggested a contemporary salad on the ceiling. We had chervil, artichokes and bean pods in plaster and I did the fresco around that. In total, I was there for nine weeks,’ recalls Miss Campbell.

‘In contrast, I did a hand-painted wall for Bill Ainscough, at Harrock Hall in Lancashire. It is a very different technique and it took me several months to complete. With true fresco, you only have between 24 and 48 hours before the plaster goes off — you have to be quick. It is a craft as well as an art.’

Abstract fresco artist Charles Snell would agree. With his family’s house-renovation business, he practised different building trades, including plastering. It was when running a print studio with his wife, Lianne (together, they are Aster Muro), that he thought about pairing plastering with his creative skills.

‘I never set out to be a fresco artist,’ he admits. ‘I was a printmaker and graphic designer, but I started to experiment putting pigment in plaster. I didn’t realise that what I was doing was fresco. Someone pointed it out to me and I started looking into it.’

Aster Muro’s work in the reading room of an elegant Hereford Regency house demonstrates how well this style works for contemporary design. Commercial clients are interested, too. In June 2020, an 860sq ft wall fresco was unveiled at MediaCityUK, in Manchester.

It is the largest contemporary abstract fresco in the country, achieved with very different tools. ‘We used industrial sprayers for the plaster layers and huge spatulas with extendable handles to apply pigments,’ reveals Mr Snell. ‘It was like a big expensive paintbrush, really; we were able to do it in five or six hours. We’ve created proper, abstract Expressionism. It’s not like traditional fresco, but it’s the same process — and it will last.’

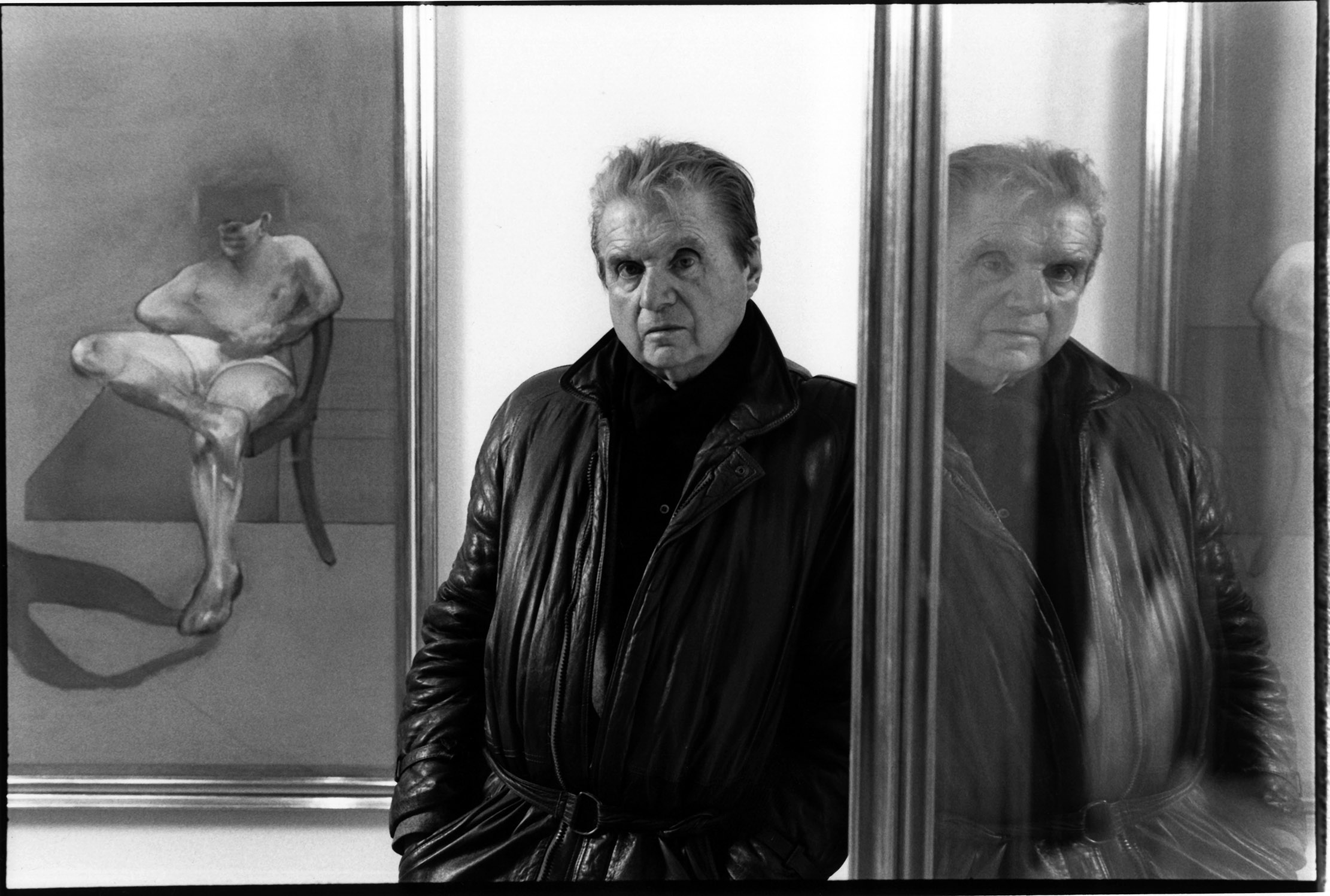

In Focus: The animalistic artworks of Francis Bacon

Martin Gayford considers the importance of snarling creatures, human and otherwise, in the art of Francis Bacon.

In Focus: The wartime masterpieces of Alfred Munnings

Huon Mallalieu welcomes the opportunity to see a significant body of wartime paintings alongside other works by Munnings in his

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabinQatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin has been setting the standard for Business Class travel since it was introduced in 2017.

By Rosie Paterson

-

Six of the best Clematis montanas that every garden needs

Six of the best Clematis montanas that every garden needsClematis montana is easy to grow and look after, and is considered by some to be 'the most graceful and floriferous of all'.

By Charles Quest-Ritson

-

In Focus: How the 'Tottering Hall' cartoonist became a sculptor

In Focus: How the 'Tottering Hall' cartoonist became a sculptorBest known as the creative force behind Dicky and Daffy, it was her son’s death that prompted Annie Tempest to learn ‘the grammar of the sculptor’s language’, discovers Ian Collins.

By Country Life

-

In Focus: How Italy inspired JMW Turner

In Focus: How Italy inspired JMW TurnerMary Miers considers how the country that fascinated Turner from youth shaped his artistic vision.

By Mary Miers

-

In Focus: Why the eerie thrives in art and culture

In Focus: Why the eerie thrives in art and cultureThe tradition of ‘eerie’ literature and art, invoking fear, unease and dread, has flourished in the shadows of British landscape culture for centuries, says Robert Macfarlane.

By Country Life

-

In Focus: John Hassall's iconic travel posters

In Focus: John Hassall's iconic travel postersThe works of British poster king John Hassall remain a breath of fresh seaside air, says Lucinda Gosling.

By Country Life

-

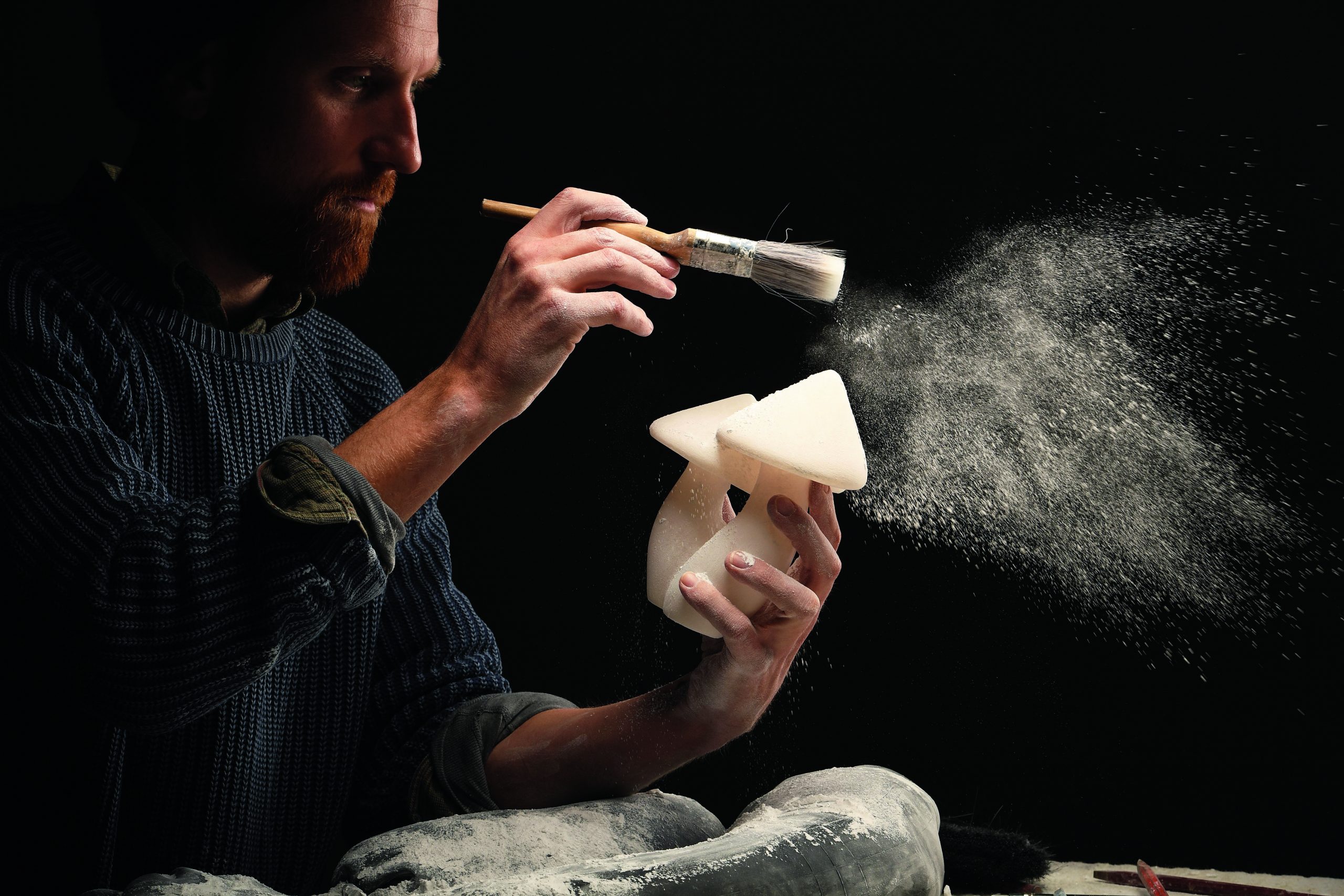

In Focus: the fungi sculptures that bend stone into soft, flowing forms

In Focus: the fungi sculptures that bend stone into soft, flowing formsThey may look as delicate and organic as the real thing, but Ben Russell’s sculptures of fungi, cacti and roots will outlast us all, believes Natasha Goodfellow.

By Country Life

-

Why a good frame can be a work of art in its own right

Why a good frame can be a work of art in its own rightCatriona Gray retraces the history of frames, admires the craftsmanship required to make them and discovers what's the best way to preserve them.

By Country Life

-

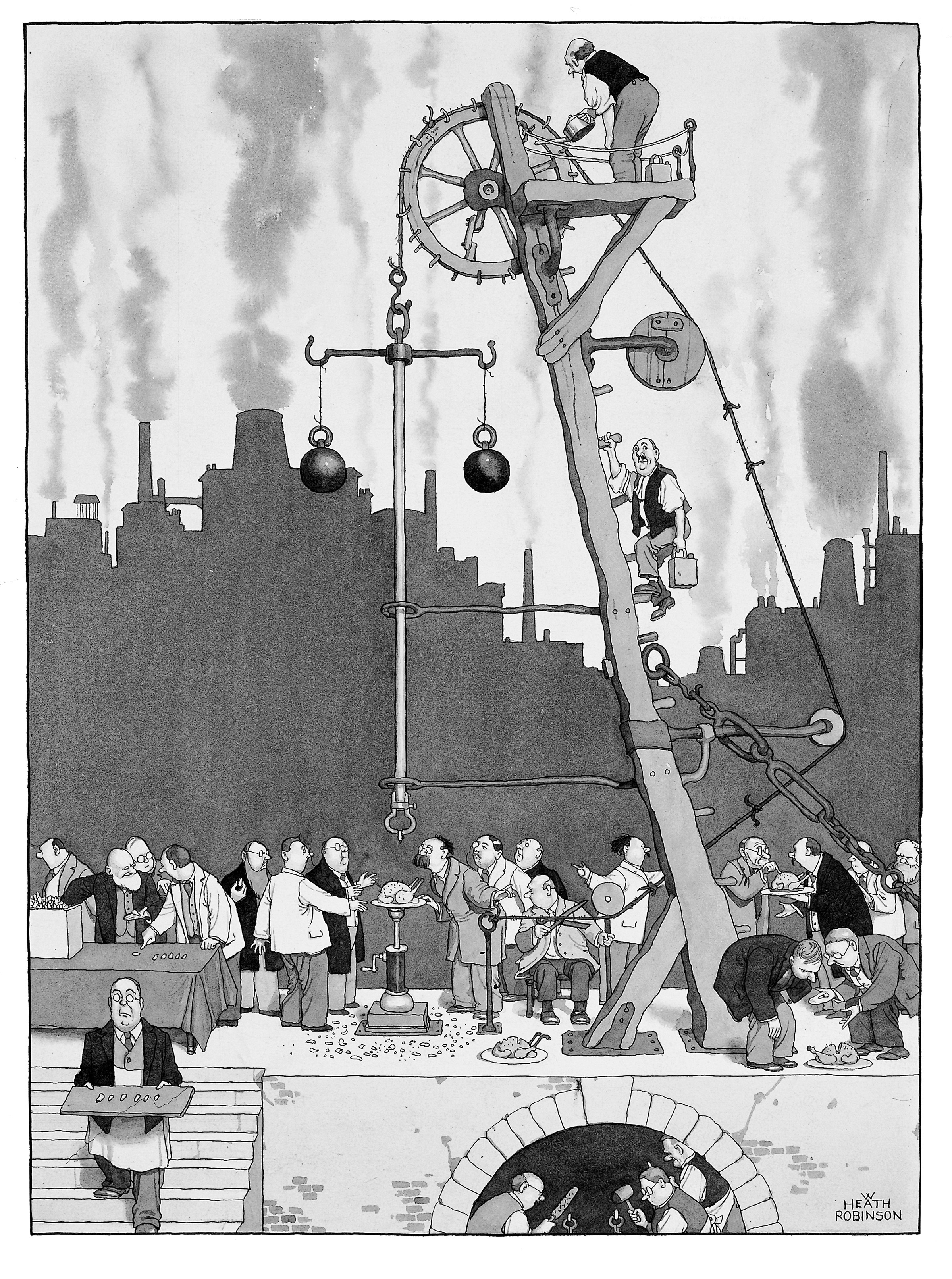

In Focus: The Heath Robinson Museum at Pinner, home to decades of gently satirised modern life

In Focus: The Heath Robinson Museum at Pinner, home to decades of gently satirised modern lifeHuon Mallalieu tells the story of the small museum in Middlesex, where you'll find the last records of the county before it became overrun by suburbia.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

In Focus: How British artists contributed to the uncanny, desirous world of Surrealism

In Focus: How British artists contributed to the uncanny, desirous world of SurrealismMichael Murray-Fennell delves into the subconscious, the uncanny, war and desire and discovers the contribution made by British artists to the Surrealist movement.

By Country Life