In Focus: The art of Andy Warhol, the 'the anti-William Morris', whose vision shaped the world as we know it

With his focus on consumerism, celebrity and counter-culture, Andy Warhol (1928–87) helped to create today’s world. Michael Murray-Fennell considers the influential Pop artist.

Growing up in poverty in an Eastern European community in 1930s Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Andrew Warhola lived on a thin soup of water, salt, pepper and ketchup. ‘What I used to dream about,’ he later recalled, ‘was having a glass of fresh orange juice and a bathroom of my own.’

In 1962, in a nod to those dreams, Andy Warhol — as he was known by then — painted 32 Campbell’s Soup cans, each representing a different flavour, from asparagus to vegetable (as well as tomato). A Los Angeles gallery presented these paintings as bona fide works of art, on the same level as the Old Masters and living Abstract Expressionists, such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, who were then the critics’ darlings.

Many derided the show; a neighbouring gallery stocked some of the real soup cans, carrying a sign in its window: ‘Do Not Be Misled. Get the Original.’

Yet Warhol’s point was a serious one: the consumer household goods of America were as valid a subject for art as any and could be simultaneously celebrated and critiqued. In blurring the distinction between art and life, he had inherited the mantle of Marcel Duchamp, whose readymade sculpture of a signed urinal had caused such a stir in 1917.

He began in the 1950s as a successful New York-based fashion illustrator for magazines — ‘the go-to guy for footwear’ — but his reputation is built firmly on his Pop Art work of the 1960s, for which his earlier training in graphic design was the perfect preparation. He preferred the term Commonism to Pop Art — ‘the art of giving the familiar a supra-familiarity’.

Warhol was the anti-William Morris, embracing the machine with his screen prints and taking particular care to eliminate any sense of craft (although do not be fooled: it is there). His re-creations of Brillo Boxes were so faithful to the original that, when a Swedish museum later organised a Warhol retrospective, it simply ordered a set of packing boxes from Brillo directly.

“On seeing one of his ‘clouds’ escape over the New York skyline, he murmured, ‘that would be the end of painting’. It remains a brilliant and beautiful idea.”

He encouraged and embraced this radical corrosion of what Art should be, revisiting and repeating his work, driven by a combination of both artistic and commercial impulses. Thirty-two Campbell’s Soup cans became 100 and he screen printed multiple Marilyn Monroes. Much has been made of Warhol’s Greek Orthodox upbringing and the question of how religious he remained; whatever the exact truth, his portraits of Coca-Cola bottles, dollar bills, tabloid pages and Hollywood stars certainly emulate the simplicity of Byzantine icons.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Warhol began moving from paintings to installations. Silver Clouds was a collection of metallic helium-filled balloons that floated through a gallery. On seeing one of his ‘clouds’ escape over the New York skyline, he murmured, ‘that would be the end of painting’. It remains a brilliant and beautiful idea.

Fox Trot, a diagram with foot-prints and arrows, actively encouraged the viewer to recreate the illustrated dance steps, breaking down the distinction between art and audience. People dancing in the gallery created what was called a ‘happening’. Today, participation art in everything from museums to Cities of Culture owe not a little to Warhol.

The Factory, the artist’s New York studio for much of the 1960s, was conceived by Warhol as a home for more of these ‘happenings’ and the cool social scene he created there fed his rapidly growing reputation. Musicians such as Lou Reed and up-and-coming actors including Dennis Hopper all hung out in the silvered interior with Warhol’s collection of impossibly gorgeous youths. He was moving into avant-garde film-making and documented many of The Factory’s faces, simply asking them to sit without instruction in front of the camera for three minutes. The most successful of these filmed portraits reveal something of the person behind their pose.

On June 3, 1968, Warhol was shot by the radical feminist Valerie Solanas. He almost died and the desperate operation to save his life forms the bravura opening of Blake Gopnik’s engrossing new biography of the artist. When recovering, he had his scarred torso photographed: ‘The cliché that Warhol was his own greatest work of art came true on the surface of his body.’

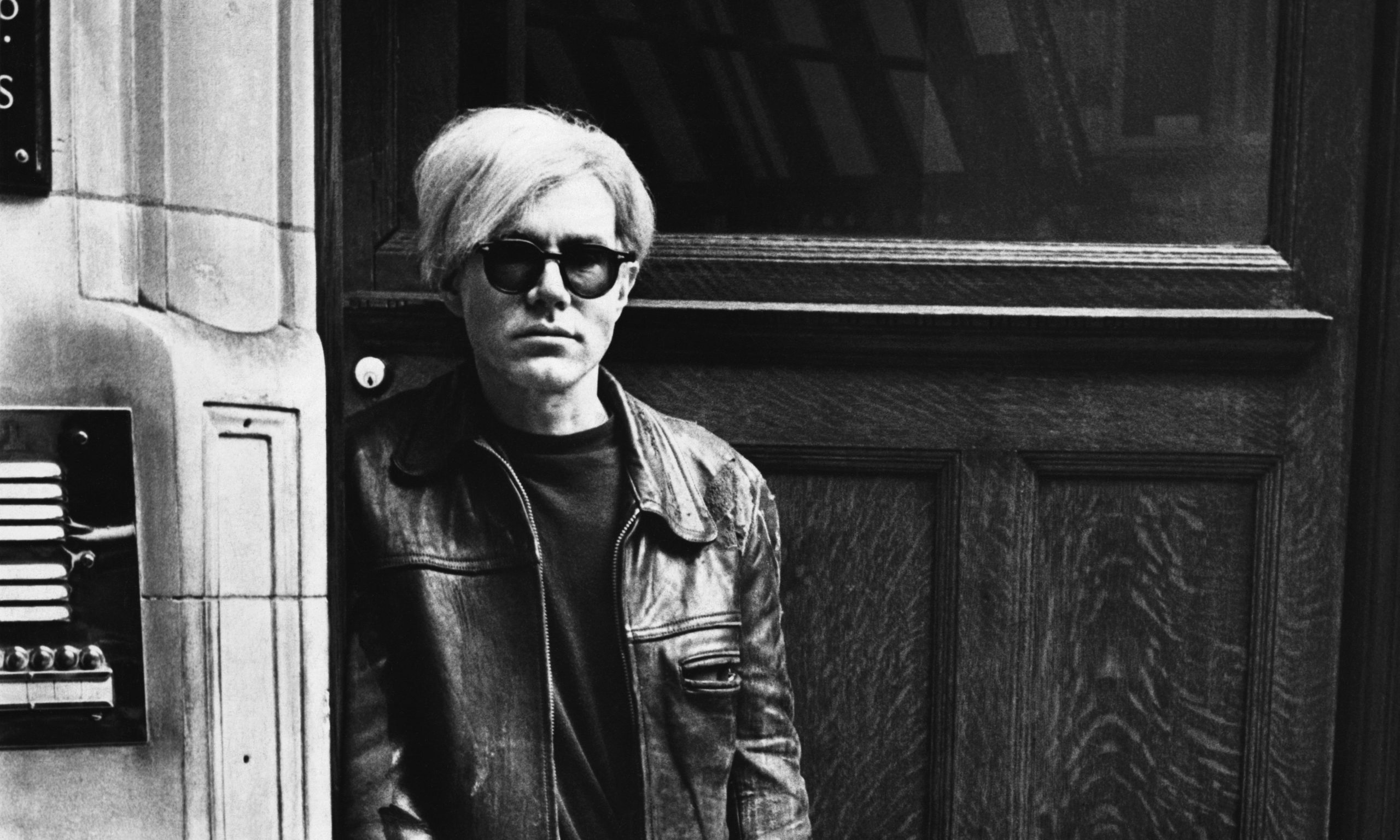

‘Andy’s a promoter who also creates — and his greatest creation is himself,’ remarked one of his collaborators. Mr Gopnik, whose biography separates the facts from the fiction — the latter often created by Warhol himself — refers to ‘the living sculpture called Andy Warhol’. He was the Pop artist who became a Pop phenomenon and, in his dark sunglasses and silver wig, almost as recognisable as those icons — Monroe and Elvis — he’d helped to create.

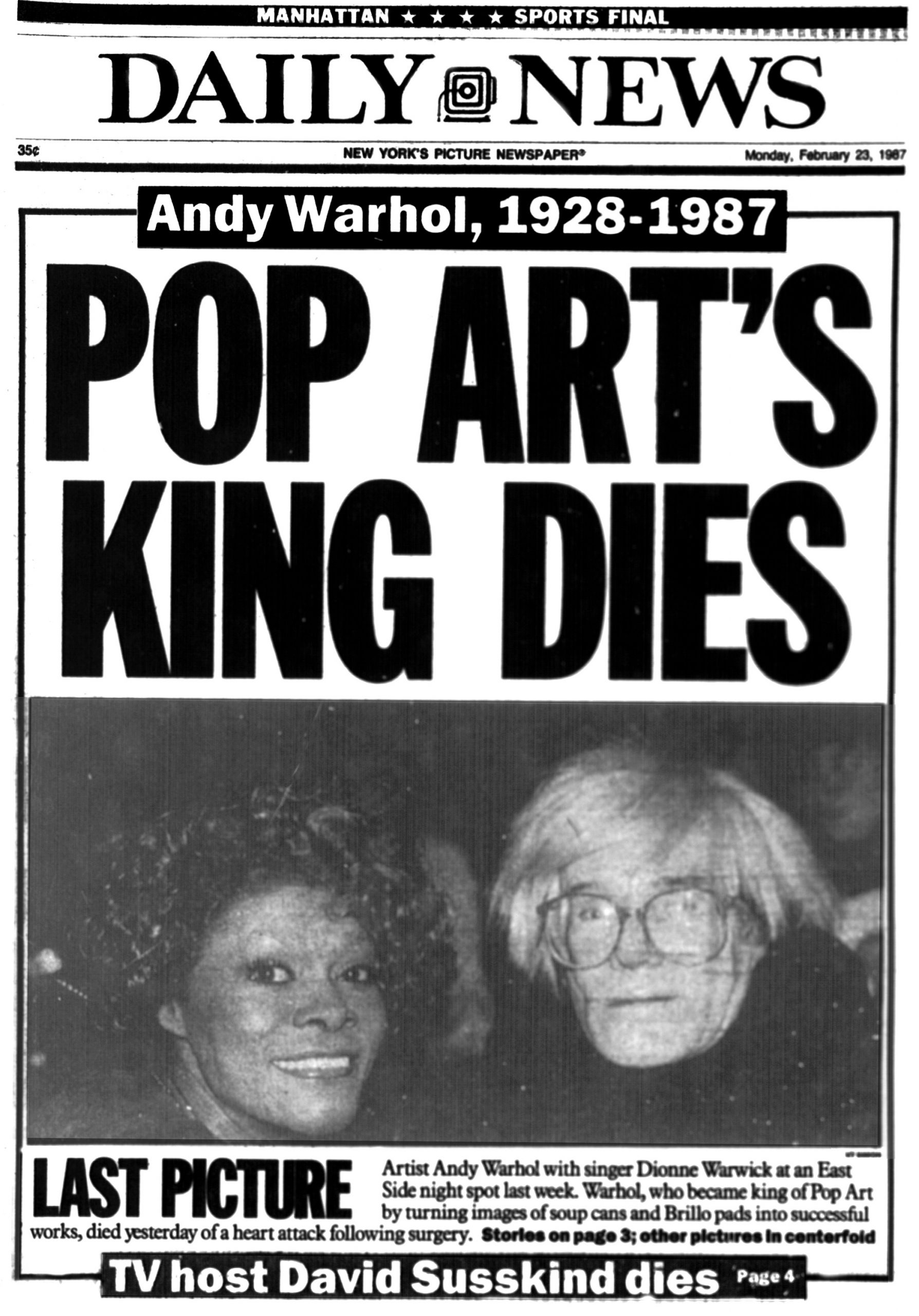

Shortly before he was shot, Warhol had traded his Factory setting for a new, more professional one, the Studio, and his art expanded into a multi-media universe, including magazines and TV. After a career spanning four decades, Warhol died in 1987 in his beloved New York.

‘Everything is art, and nothing is art,’ he once claimed and, although we should be wary of believing he subscribed to everything he said, he certainly broadened the definition of what constituted art. A conceptual artist par excellence, Warhol not only shaped much of Modern art, but also, from reality TV to today’s selfie culture, much of modern life.

In Focus: How mass tourism to the seaside produced an entire era of iconic Modern art and architecture

Clive Aslet examines how seaside resorts used Art Deco to catch the eye, spurring on a movement of Modern designs

The Scottish artists who mashed up Dali and Boticelli to make their mark in the 20th century

Duncan MacMillan applauds an exhibition that reassesses the contribution made by Scottish artists to the great movements of Modern art.

In Focus: Bomberg, the trailblazer who led the way for modern British art but died an impoverished war veteran

Coinciding with the sixtieth anniversary of the artist’s death, the touring exhibition of David Bomberg’s work is entering its final

In Focus: how technology can transform old art, producing replicas not to deceive, but to stimulate artistic thinking

Modern digital technology is transforming our understanding of the context and meaning of historic works of art. Emma Crichton-Miller investigates.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.