In Focus: T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land, the poem of broken modern civilisation that seems more apt than ever

On the 100th anniversary of its publication, Julie Harding asks why T. S. Eliot’s great poem The Waste Land, with its devastating vision of a broken modern civilisation, still resonates so strongly today.

On Margate Sands. I can connect Nothing with nothing.

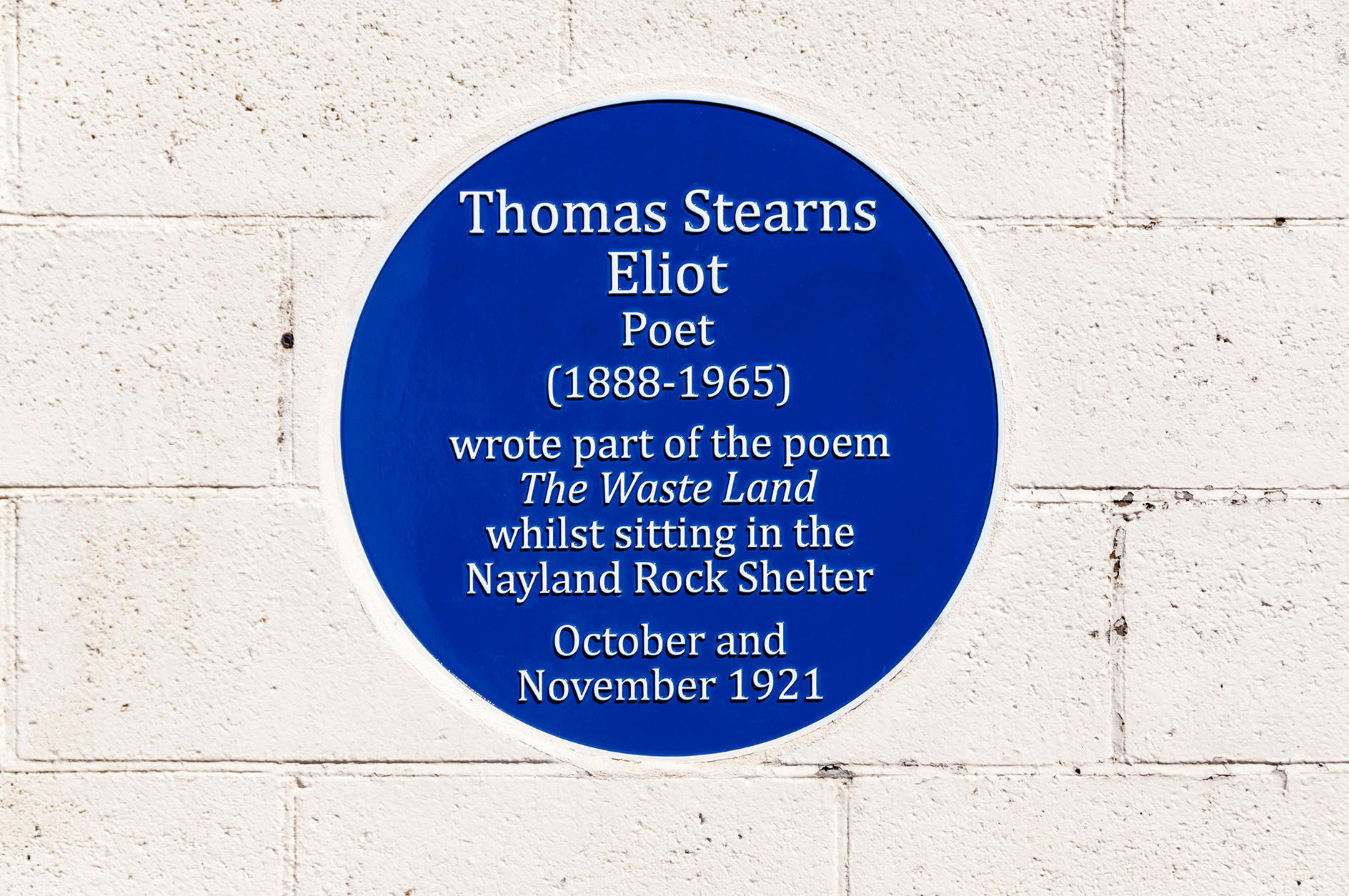

Thomas Stearns (T. S.) Eliot crafted these short lines that form a part of his fractured epic The Waste Land in October 1921, as he sat in the inauspicious Nayland Rock Shelter (granted Grade II-listed status in 2009) on the promenade of the Kent seaside resort.

The American poet was struggling to write, battling with the pressures of a taxing marriage to Vivien Haigh-Wood, and had recently endured a tense family visit that saw his ageing mother, Charlotte, travel to England from America. He was living on his nerves, quite likely suffering from a nervous breakdown or, as he later stated, from ‘aboulie’ — consequently, he was about to be granted a three-month sabbatical from his job at Lloyds Bank. At this point, he was seemingly unable to personally connect anything with anything.

It is often easy to feel the personal anguish woven into The Waste Land, but the 434 lines that make up this work — now widely regarded as one of the greatest poems in the English language — are nothing if not complex. Indeed, critics have critiqued it — and over-critiqued it — for 100 years, since its publication, in October 1922, in The Criterion, the journal Eliot founded, and in The Dial in the US a month later. Despite Eliot’s contemporary Amy Lowell, a poet and fellow American, calling it ‘a piece of tripe’, The Waste Land scooped The Dial’s lucrative annual literary prize.

Since then, generations have appreciated its rich tapestry of literary references, from Homer to Shakespeare, as well as its myth (the title is owed to Jessie Weston’s examination of the Holy Grail in From Ritual to Romance), religion, the collapse of civilisations, cyclical regrowth, disparate polyphonic voices, series of vignettes and failed relationships. All in all, this mingling of discordant elements, that ‘heap of broken images’ conveyed in part one, The Burial of the Dead, adds up to a potent rendering of a metaphorical land as sterile and arid, a disordered, dysfunctional, broken place and its maimed people living futile lives, shattered by the armageddon of the First World War.

‘Only There is shadow under this red rock, (Come in under the shadow of this red rock),’ is one such mention of this barren land that remained after the American poet Ezra Pound had performed his ruthless, self-confessed ‘caesarean operation’ on Eliot’s original version. Near the end of the editing process, however, Pound had written to the creator, saying: ‘Complimenti, you bitch. I am wracked by the seven jealousies.’

Yet what of actual places, for many seemingly diverse locations are mentioned in The Waste Land, if fleetingly? London. The Cannon Street Hotel. The Strand. The Isle of Dogs. Highbury, Richmond and Kew. Moorgate. London Bridge. Munich’s Hofgarten. Thebes. Carthage. Jerusalem. Athens. Alexandria. Vienna. That desert. Mountains.

‘When he’s naming other cities, he’s playing with time and place. He’s going back to the likes of Athens and through to London, encapsulating a decline in human history over thousands of years,’ explains Dr Fran Brearton of Queen’s University Belfast.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘But Eliot doesn’t tend to be talked about much as a poet of place. There isn’t that kind of specificity compared with how some poets at the time are so deeply rooted. Think of Hardy in the Wessex countryside and how central place is to him.

‘Eliot references specific places and the number of different locations map onto the different voices that are changing all the time and he uses these to convey that sense of dislocation.’ As for Margate, Dr Brearton, suggests: ‘Why Margate Sands is something we could think about indefinitely. It is Margate Sands, but it could almost be anywhere.’

The Waste Land may reference the waves, yet it is equally — if not more so — a poem of a river, specifically the River Thames, which carries with it the detritus of modern life: ‘Empty bottles, sandwich papers, silk handkerchiefs [contraceptives], cardboard boxes, cigarette ends…’ For many critics and devotees of The Waste Land (once you have read it, it never quite leaves you), London, through which this dirty river flows, is the towering and tangible place of the poem (if anywhere can be tangible), partly summed up in those haunting lines: ‘A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, I had not thought death had undone so many.’ Apart from its reference to Dante’s The Divine Comedy, think of the monotony of commuting and of humdrum 20th-century human existence, a living death and the grief for incomparable loss.

However, if human life is empty, so, too, is London at certain times, according to Professor Jason Harding of Durham University. ‘In the 1920s, there was a massive depopulation of this area, so the parish churches mentioned — such as St Mary Woolnoth and Magnus Martyr — have no one to worship there. Eliot was working in the City when he was writing this poem, feeling miserable, and he would walk out in his lunch hour and visit one of the beautiful city churches and that is resonant in the poem.’

This Easter, however, those churches were full again thanks to Fragments: The Waste Land 2022, a bespoke, one-off experiential festival to mark the centenary. This brought music and musings delivered in the very churches Eliot had visited, with St Mary Woolnoth hosting the opening and closing celebrations and St Magnus the Martyr hearing music by Erland Cooper, together with poems read by performers, including the actor Toby Jones.

A century earlier, following his trip to Margate, Eliot travelled on to Switzerland, where he underwent a psychiatric rest cure in the hands of Dr Roger Vittoz, which unlocked his powers of creativity. Part five, What the Thunder Said, flowed and it teems with mention of mountains: ‘Of thunder of spring over distant mountains’ and ‘There is not even silence in the mountains’.

‘I think Eliot is writing the end of the poem surrounded by those mountains and imagining himself in the heart of Europe, worried whether Communism will sweep away the civilisation and culture he wants to hang on to,’ intimates Prof Harding. ‘Mountains are prominent in Romantic literature as places of transcendence or of vision. In high places, real wisdom will be communicated. There are thunder clouds gathering, so it is pregnant with anticipation, but I think that, although the poem is waiting for that revelation, it’s not quite getting it.’

When The Waste Land was poised for print, Eliot wrote to the novelist Virginia Woolf and said that he believed it to be his best work yet. It was an apposite statement and, if his magnum opus is not solidly rooted in any cityscape or landscape particularly, it is as firmly fixed in the 21st-century psyche as it was in the 20th and is likely to be equally entrenched for centuries to come.

Celebrating the centenary of The Waste Land

T.S. Eliot worked for Faber and Faber for 40 years, until his death in 1965. To mark the centenary of The Waste Land, Faber is publishing The Waste Land: T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and the Making of a Masterpiece, by award-winning biographer Matthew Hollis, in October.

Earlier this year, the publishing house released The Waste Land: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts, which shows the manuscript in colour for the first time. Additionally, in association with the T. S. Eliot Foundation, it has already released an audiobook recording of Edoardo Ballerini reading the epic poem.

Carla Carlisle: 'Spending billions to send a man to the Moon seemed a terrible distraction and an insane waste of money'

Carla Carlisle recalls her memories of the moon landings 40 years on.

Credit: Getty

Jonathan Self: The greatest novel of the 20th century? Maybe, but 'Ulysses' still sent me to sleep within three pages

Jonathan Self looks back on some of the great books published exactly a century ago.

Credit: Alamy

The true meaning of Dumbledore, Chiggypig, Hornywink and Lang lugs, and the other old English animal names all but lost to us

The colourful and beautiful archaic names given to the animals and birds of Britain are in danger of being lost

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stile

Thomas Hardy’s depictions of a fictional Wessex and his own dear Dorset are more accurate than they may at first

Julie Harding is Country Life’s news and property editor. She is a former editor of Your Horse, Country Smallholding and Eventing, a sister title to Horse & Hound, which she ran for 11 years. Julie has a master’s degree in English and she grew up on a working Somerset dairy farm and in a Grade II*-listed farmhouse, both of which imbued her with a love of farming, the countryside and historic buildings. She returned to her Somerset roots 18 years ago after a stint in the ‘big smoke’ (ie, the south east) and she now keeps a raft of animals, which her long-suffering (and heroic) husband, Andrew, and four children, help to look after to varying degrees.