In Focus: Sir Thomas Lawrence, the child prodigy who painted Queen Charlotte

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) graduated from being a child prodigy who sold his first sketch aged five to a great portraitist who met his match in royal women. This year he is celebrated in an exhibition at The Holbourne Museum; Matthew Dennison finds out more.

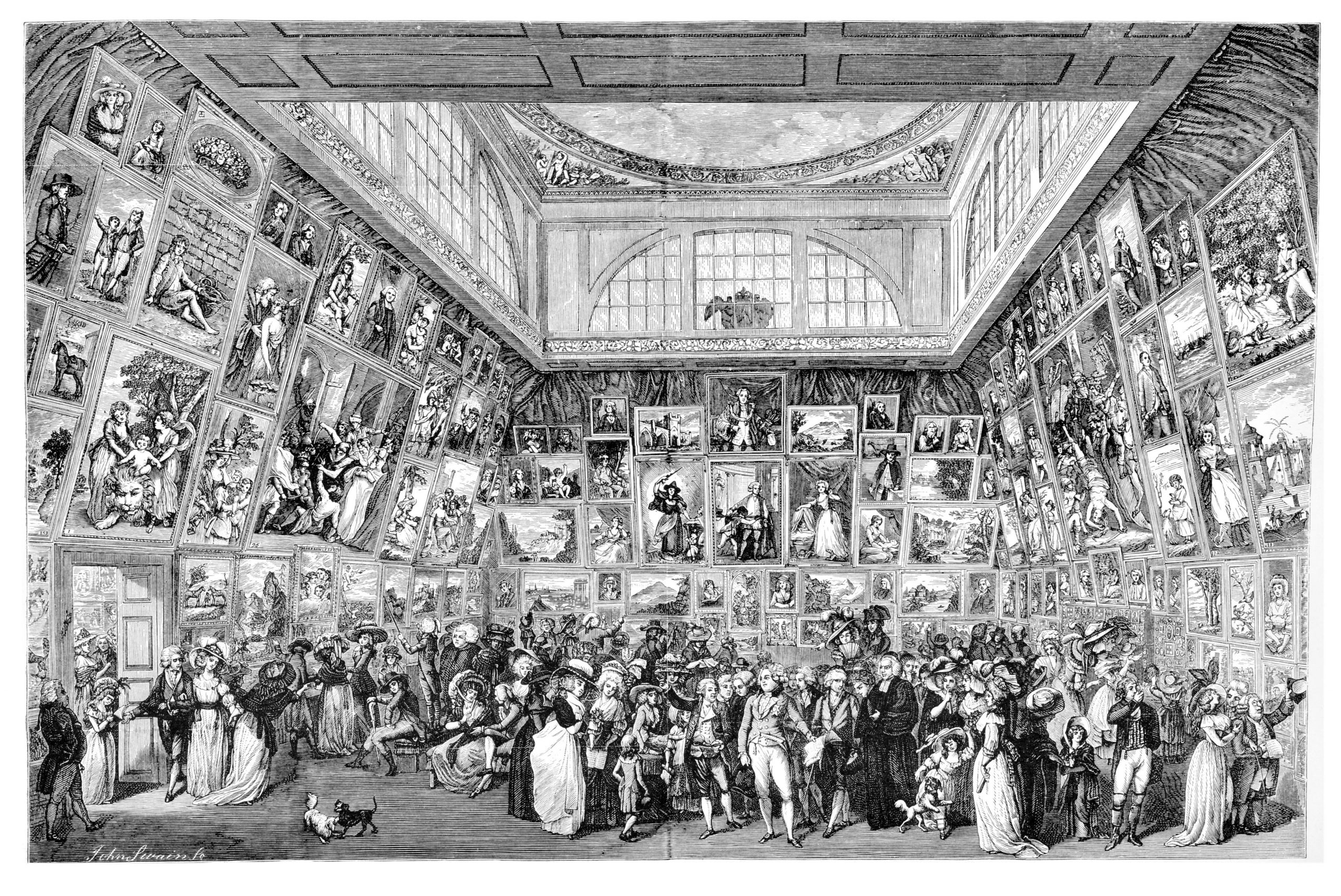

Thomas Lawrence was never paid for the portrait he painted, in 1789, of George III’s wife, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Instead, the precocious 20 year old submitted the picture to the Royal Academy (RA) in the spring of 1790, where it was judged among ‘the best Portraits in the Room’.

Neither King nor Queen agreed. Despite initiating the commission, Charlotte was upset by young Lawrence’s ‘rather presuming’ manner and granted him a single sitting. Her own manner on that occasion survives in primary sources as markedly prickly. From her sniffy hauteur, Lawrence wrested nevertheless an image of tranquil dignity, sumptuous in its treatment of the gauzy layers of her frock and the Queen’s milky complexion, spoiled by excessive snuff-taking and the anxieties of 18 months that had witnessed her husband’s mental collapse, the horrors of the French Revolution and her eldest son’s insensitive lobbying for royal power.

Whatever the opinion of the royal couple, it was a work of considerable ability that played its part in consolidating Lawrence’s fledgling reputation among London’s connoisseurs. Two years later, lack of royal enthusiasm notwithstanding, he was appointed painter-in-ordinary to George III, following the death of Joshua Reynolds.

In 1794, aged 25, Lawrence was elected a Royal Academician. For the remainder of his career, he earned golden opinions for work of scintillating brilliance, in which theatrical swagger partnered romantic sensibility and vivid flashes of character, all realised in dazzling brushwork.

Lawrence had been undaunted by the honour of the Queen’s commission in 1789. He had sold his first portrait sketch at the age of five. In 1788, he wrote matter of factly to his mother: ‘Excepting Sir Joshua [Reynolds], for the painting of a Head, I would risk my reputation with any painter in London.’ This verdict is supported by a compelling pastel portrait he painted that year of elderly bluestocking Elizabeth Carter, apple-bright cheeks satin-sheened in their translucency, each soft ruffle of her muslin cap crisply delineated.

The artist was a child prodigy. The novelist Fanny Burney had described him, in 1779, as ‘a most lovely Boy of 10 years of Age, who seems to be not merely the wonder of [his] Family, but of the Times, for his astonishing skill in Drawing’. His fame would continue to grow; shortly before his death, Lawrence’s unfinished portrait of the 4th Earl of Aberdeen was acclaimed as ‘certainly… the finest portrait in the world’.

Since his father’s bankruptcy, when Lawrence was 11, this skill had been essential to the family’s survival, prompting a move from Devizes, Wiltshire, to Bath in Somerset — where the teenage wonder’s fashionable sitters included Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire — and thence to London. Following public exhibition of his portrait of the Queen, Lawrence set up studio in Old Bond Street.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Until their deaths in 1797, he continued to live with his parents, meeting the expenses of the house at 57, Greek Street. Later, he moved to Russell Square, where he remained until his death in January 1830, assembling an exceptional collection of more than 4,000 Old Master drawings. These included works by Michelangelo, that, despite his high fees, proved a considerable drain on his resources and contributed towards debts approaching £40,000.

Lawrence was a draughtsman of singular ability and proved equally adept in his studies of wealthy financiers, actors, Napoleonic-era heroes and political figures, such as the Persian envoy, Mirza Abul Hasan, whose portrait he completed in three weeks in 1810. Royal women alone appear to have caused him a degree of difficulty: in 1825, the French press reacted scathingly to his portrait of the duchesse de Berry — its awkward stiffness recalls his likeness of George IV’s sister, Mary, Duchess of Gloucester, painted the previous year.

In his treatment of George himself, however, despite unpromising material, Lawrence showed his mettle. Painter and prince first met in 1814 and the full-length portrait Lawrence completed on that occasion led to the King’s long-running commission to paint representatives of Britain’s allies in the Napoleonic wars, that gallery of swaggering magnificence that today lines the Waterloo Chamber at Windsor Castle.

With equal elan, Lawrence invested the corpulent, rouged, bewigged monarch with intimations of the same Byronic heroism that transformed, for example, diminutive Archduke Charles of Austria into a model of masterful dignity, a towering figure in his uniform of heavily braided scarlet and white, outlined against an apocalyptic sky. The triumph of Lawrence’s state portraits of George IV offers a healthy riposte to those gainsayers who queried his genius in the years after his death, happily — and correctly — now a minority.

‘Thomas Lawrence: Coming of Age’ is due to open at the Holburne Museum, Bath, Somerset, this year — www.holburne.org

Thomas Lawrence: A timeline

1769 Born in Bristol on April 13

1787 Moves to London and studies at the RA

1791 Elected associate of the RA and, in 1794, academician

1792 Appointed painter-in-ordinary to George III

1810 Patronised by the Prince Regent (later George IV)

1815 Receives knighthood

1816 Gives evidence in support of acquisition of the Elgin Marbles

1820 Elected president of the RA

1830 Dies at home in London on January 7. The funeral is held at St Paul’s Cathedral and his remains are buried in Painters’ Corner

Lawrence of Arabia's house in Oxford comes to the market

The house where Colonel Thomas Lawrence – better known as T. E. Lawrence, and Lawrence of Arabia – spent most of

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.

-

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa Harrison

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa HarrisonThe novelist, children's author and nature writer Melissa Harrison joins the podcast to talk about her love of the natural world and her new app, Encounter.

By James Fisher

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes