In Focus: Raphael the painter, draughtsman, architect, poet... and perhaps the ultimate Renaissance man

A brief life, a prolific output, an immortal legacy: the epitome of the Renaissance man, ‘the divine Raphael’ remains the paragon of perfection and aesthetic excellence, says Susan Jenkins.

Raphael Santi (or Sanzio) of Urbino was the epitome of the well-rounded Renaissance man. He was still in his 20s when he became famous for his many talents as a painter, draughtsman, architect, poet and tapestry designer — and he is still celebrated just as much today, not least in the National Gallery’s latest Raphael exhibition, which runs until the end of July.

A towering figure of the Italian Renaissance alongside contemporaries Leonardo da Vinci (about 1450–1519) and Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), he echoed them in attracting the prestigious patronage of Popes Julius II and Leo X. He was also known for his taste for learned company and intellectual endeavours, which was relatively unusual among artists at the time.

Many of the anecdotes relating to Raphael’s life and (multiple) loves were recorded by artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari (1511–74) in his The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects of 1550. Raphael was wealthy and successful in his own day, living, according to Vasari, ‘not like a painter, but like a prince’. His reputation as a great artist outlived him, especially in England, where Reynolds, president of the Royal Academy from 1768–92, proclaimed that: ‘The excellency of this extraordinary man lay in the propriety, beauty and majesty of his characters, the judicious contrivance of his composition, his correctness of drawing, purity of taste…’

The young Raphael trained in the workshop of his father, Giovanni Santi, who painted for the Duke of Urbino’s court in Le Marche, eastern Italy. After he was orphaned at the age of 11, he fell under the influence of Pietro Vannucci (‘il Perugino’) from Perugia in nearby Umbria.

Raphael’s early output included several altarpieces for local towns. The first he painted as an independent ‘master’ was The Coronation of St Nicholas of Tolentino, of 1500–01, for the church of Sant’Agostino in Città di Castello. Vasari notes that Raphael’s second altarpiece for that town, The Crucified Christ with the Virgin Mary, Saints and Angels (the so-called ‘The Mond Crucifixion’, now in London’s National Gallery), was commissioned by wool merchant Domenico Gavani for his burial chapel in the church of San Domenico. Raphael also contributed several important altarpieces to churches in Perugia during his stay there, from about 1502–05, including The Coronation of the Virgin, which was installed in the Oddi Chapel in the church of San Francesco al Prato in about 1502–03.

A young man’s ambition made him restless and, by 1504, he had moved to the Tuscan capital of Florence in the hope of attracting patronage from the Medici court. It was here he honed his skills, copying the work of Leonardo and Michelangelo. During this period, he successfully transformed the traditional iconography of the Virgin and Child by creating small-scale, intimate images in an experi- mental circular (‘tondo’) form, as seen in the ‘Terranuova Madonna’, The Virgin and Child with the Infant St John the Baptist (The Alba Madonna), (National Gallery of Art, Washington, US), and The Holy Family with a Palm Tree, 1506–07 (National Galleries Scotland).

The career-defining moment came in 1508, when he was invited to Rome by the greatest patron of the age, Pope Julius II, to decorate his private rooms in the Vatican Palace. This move transformed Raphael’s artistic status. First working with fellow painter Giovanni Antonio Bazzi (‘il Sodoma’, 1477–1549) on Pope Julius’s private library, the Stanza (Room) della Segnatura, Raphael alone secured the commission for the following three rooms, the Stanza di Eliodoro, (where the Pope received visitors), the Stanza dell’Incendio and the Sala di Costantino. The artist was further honoured in 1511, when the Pope appointed him his Scriptor Brevium (papal scribe), a symbolic role that was a mark of great favour.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Raphael took exceptional trouble with the design and painting of his ground-breaking frescos for the Pope’s private apartments, to which he brought a new level of artistic and intellectual achievement. He probably began work in the Stanza della Segnatura in 1508–09 with a scene of the ‘Disputa’ or ‘Disputation of the Holy Sacrament’, depicting an earthly gathering of faithful saints and notables assembled around an altar on which stands the host in a monstrance, overseen by the Trinity in the Heavens. A further assembly of experts in the disciplines of geometry, geography and astronomy appears in the famous ‘School of Athens’ fresco of 1509–10.

Pope Julius II died midway through Raphael’s execution of the frescos for the Stanza di Eliodoro, but his successor, Pope Leo X (Giovanni de’ Medici), confirmed the artist in post. As a compliment to his new patron, Raphael chose scenes from the lives of 8th- and 9th-century Popes Leo III and IV to decorate the Stanza dell’Incendio, from 1514–17. At the same time, Leo X commissioned him to design a loggia for him in the Vatican Palace, which ran down one side of the building, ornamented with stucco and sculpture.

Raphael’s popularity in Rome encouraged him to employ several artists. According to Vasari, when he went to work, he was accompanied by 50 men ‘who kept him company to do him honour’, many of whom probably belonged to his workshop. Raphael had always collaborated with others and never baulked at supplying designs that were executed by artists under his direction. His large and organised workshop attracted talented painters, notably Giulio Romano (1492/9–1546), who was his principal assistant. After his master’s death, Romano successfully completed the Sala di Costantino, from 1520–24.

In 1514, Raphael received the most important and complex commission of his career when Pope Leo X asked him to design a series of tapestries depicting the Acts of the Apostles. He rose to the challenge and the series was woven in Pieter van Aelst’s workshop in Brussels before being hung in Rome.

The artist was rapidly establishing his status as a polymath proficient in many different areas of creative activity. In 1514, Pope Leo appointed him chief architect for St Peter’s and the Vatican on the death of Raphael’s kinsman Donato Bramante (1444–1514), also from Urbino. This appointment dovetailed with his increasing knowledge of Rome (in 1515, the Pope created him ‘prefect of marbles and stones’ and commissioned him to produce a survey of ancient Rome) and also recognised his developing expertise in architectural design. This had been demonstrated in schemes such as the design of the burial chapel for papal banker Agostino Chigi in the church of Santa Maria della Pace, Rome, with its coloured marble interior and bronze wall-mounted roundels, begun in 1510 and later completed by papal architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

The life and times of Raphael

- 1483 — Born in Urbino in Le Marche and calls himself ‘da Urbino’ throughout his life

- 1494 — Orphaned on the death of his father Giovanni Santi, a painter

- 1500 — Qualifies as an independent ‘master’

- 1500–01 — Paints his first altarpiece, The Coronation of St Nicholas of Tolentino for the church of Sant’Agostino in Città di Castello, for wool merchant Andrea di Tommaso Baronci

- 1502–04 — Trains in the studio of Pietro Vannucci, ‘il Perugino’

- 1502–05 — Paints several altarpieces in Perugia

- 1506 — Arrives in Florence to learn by copying the works of other artists

- 1508 — Pope Julius II (reigned 1503–13) commissions him to decorate his private apartments in the Vatican Palace, Rome

- 1511 — Pope Julius appoints him Scriptor Brevium, symbolic appointment of ‘papal scribe’

- 1512 — Decorates the Villa Farnesina with The Triumph of Galatea for papal banker Agostino Chigi

- 1513 — Leo X (formerly Giovanni de’ Medici) becomes Pope

- 1514 — Pope Leo commissions tapestries of the Acts of the Apostles to decorate the Sistine Chapel

- 1514 — Appointed architect of St Peter’s in Rome on the death of Donato Bramante and becomes engaged to Cardinal Bibbiena’s niece

- 1515 — Pope Leo appoints him supervisor of Roman antiquities and excavations

- 1516–17 — Decorates Leo X’s loggia, Vatican Palace

- 1517 — Designs Villa Madama for Leo X’s cousin

- 1519 — ‘Acts of the Apostles’ tapestries hung in the Sistine Chapel for the first time

- 1520 — Dies after a violent 10-day fever and is buried in the Pantheon, Rome, at his own request

Raphael designed Roman townhouses, too, such as the Villa Madama (from about 1516) and the Palazzo Branconio dell’Aquila (now destroyed), for his friend the goldsmith Giovanni Battista Branconio dell’Aquila, of which contemporaries commented that ‘nothing more beautiful or festive may be seen in Rome’. In 1517, the artist celebrated his success by acquiring Bramante’s house, Palazzo Caprini, where he lived in princely style.

His career in Rome was dominated by papal demands and portraits of both Julius II and Leo X are among Raphael’s most revealing works of art. Painted in about 1511, that of Pope Julius in London’s National Gallery sets a new precedent with its three-quarter length formula. According to Vasari, Julius II was famous for his ‘terribilità’ (his ability to terrify), but the grey-bearded figure shown seated in a chair, rather than on a papal throne, depicts the underlying frailty of an ageing pontiff recuperating from illness, as well as expressing his absolute grip on power.

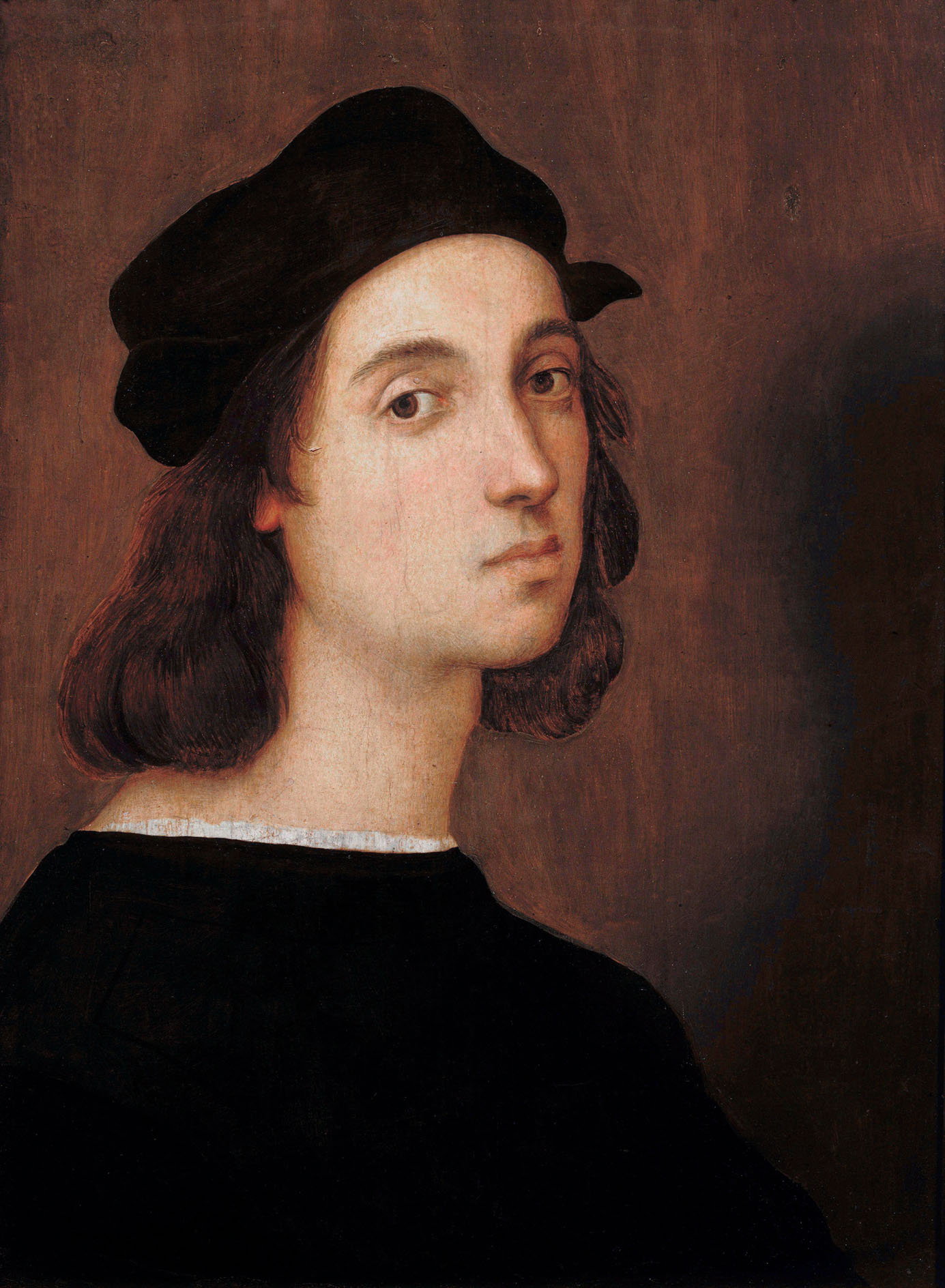

As are many artists, Raphael was interested in his own appearance and, although he only found time to paint a small number of self-portraits, he fashioned his self-image throughout his lifetime. Notable among these is Self-Portrait with Giulio Romano in the Louvre, Paris, probably painted in 1520, the last year of his life. Raphael — who, according to Vasari, could not have loved Romano more had he been his own son — stands behind his young assistant with his hand on his shoulder, symbolically anointing his artistic heir.

Raphael painted even fewer portraits of women, but among his final works is the portrait known as ‘La Fornarina’, now in the Palazzo Barberini in Rome. La Fornarina, ‘the baker’s daughter’, wears an armband inscribed ‘Raphael Urbinas’. She is believed to be the great love of his life, Margherita Luti, whose amorous activities, noted Vasari, led the artist to catch the fever from which he died.

Raphael’s short life was notable for its productivity and the beauty of the images he created. He was one of the finest draughtsmen of his generation, using drawings to plan and refine his compositions, and was one of the last great artists to use the metalpoint technique. Exquisite examples of his drawings can be seen in the current ‘Raphael’ exhibition.

Intent on shaping his legacy, he accomplished much more than that during his 20- year career: he shaped the course of Western culture. His collaboration with printmaker Marcantonio Raimondi saw his work circulate widely and, after his death, he was celebrated as ‘the divine Raphael’. At his request, he was buried in the Pantheon in Rome, the first artist to choose this symbolic location associated with the early Christian martyrs.

He is acknowledged to be one of the greatest history painters ever and creator of the most influential altarpieces, portraits and frescos ever produced. The beauty and harmony of his work has profoundly affected the European tradition of painting, so ‘the divine Raphael’ is seen as the paragon of perfection and aesthetic excellence for all time.

‘Raphael’, The Credit Suisse Exhibition, is at the National Gallery, Trafalgar Square, London WC2, until July 31. 020–7747 2885; www.nationalgallery.org.uk

The eloquence of line: Raphael’s drawings at the Ashmolean Museum

Caroline Bugler admires the beauty and expressive power of Raphael’s drawings.

Curious Question: Was St Valentine beaten to it by 1,000 years by the Welsh patron saint of love?

The arrival of St Dwynwen's day on January 25th prompts Martin Fone to recall the tale of a saint whose

The Museum of the Home, where you'll find 1990s Habitat knick-knacks, a Philippe Starck lemon squeezer and interiors inspiration far beyond the showrooms

Established a century ago to celebrate domestic interiors, the Geffrye Museum has been reborn as the Museum of the Home,

Credit: Sotheby's

Charles I’s lost painting, up for sale for the first time in nearly 400 years

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life