In Focus: Piranesi, the architect, artist and engraver whose fantasy buildings won him 300 years of fame

In the 300th anniversary year of Piranesi’s birth, Huon Mallalieu considers the architectural fantasies of one of the most widely recognised names in 18th-century Italian art: Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi began his career as a printmaker by supplying small engravings of Roman sights for the Grand Tourist trade, but he very quickly turned to much more ambitious and original compositions.

Indeed, the name Piranesi immediately conjures up large-scale etchings of fantastical prisons or capriccios of Roman monuments. He was an exciting draftsman, too, but his drawings are not so well known as so many of them are in collections such as that of the British Museum and are seldom on show — this summer, however, that is different: the exhibition ‘Piranesi Drawings: Visions of Antiquity’ is at the British Museum and, once it reopens, will run until late summer.

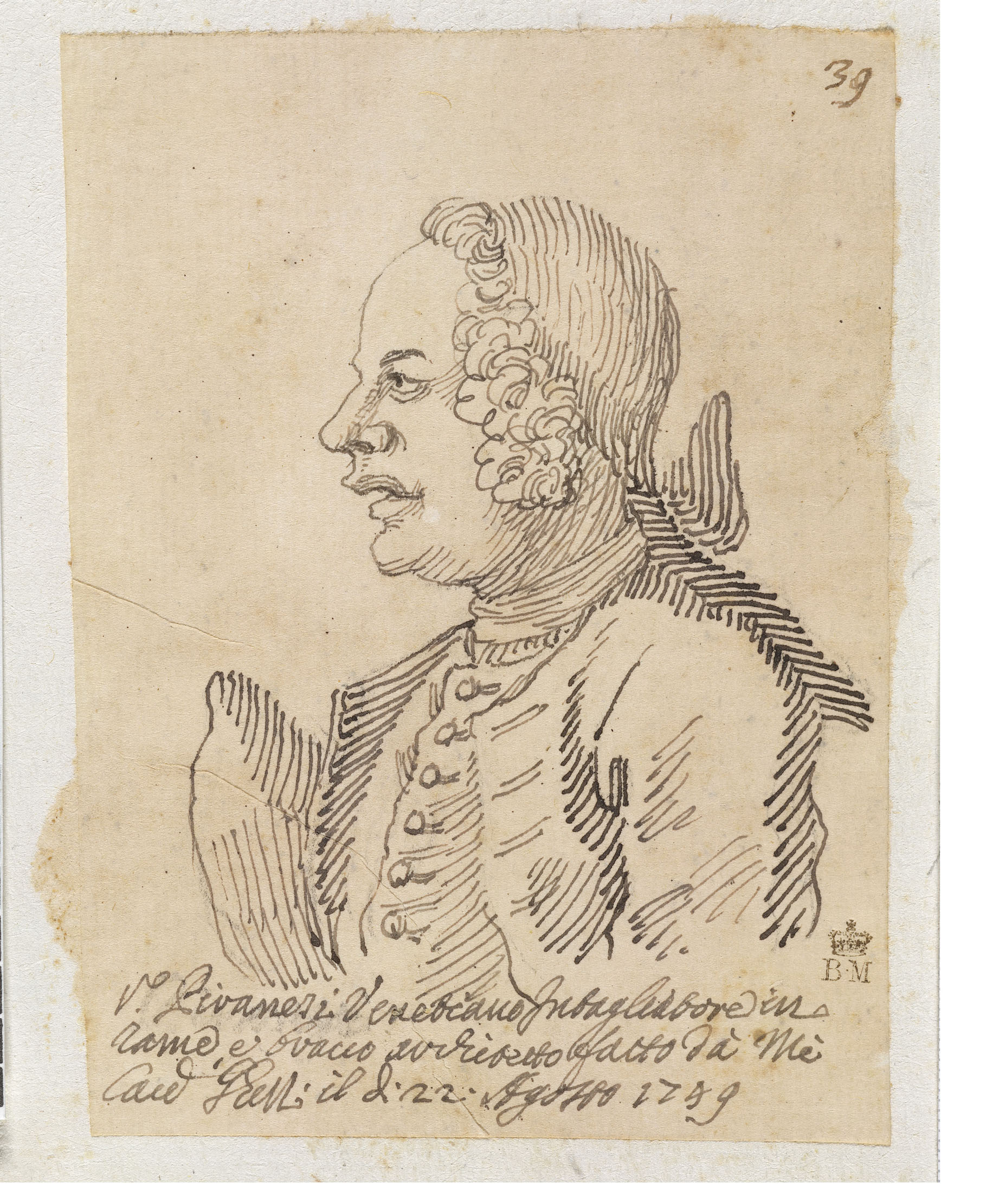

Piranesi (1720–78) considered himself to be, above all, an architect, having had some training with an architect uncle. However, there was little opportunity to practise because the Baroque building boom was over and he was responsible for only one building, Santa Maria del Priorato in Rome—and then only for its restoration. Even so, throughout life, his preferred signature was ‘Piranesi Architetto Veneziano’.

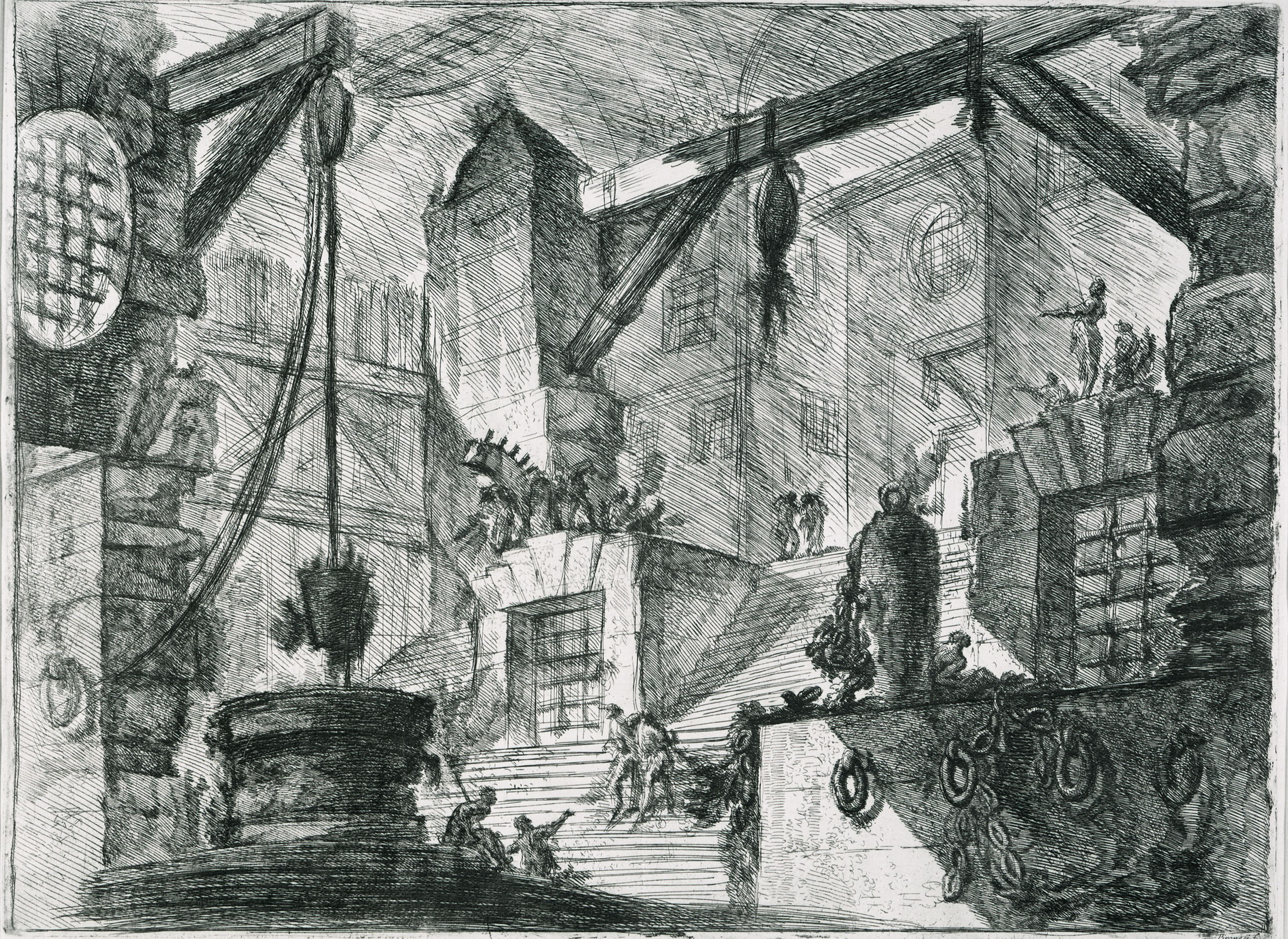

It cannot be proved, but he is also said to have studied with the Bibiena family of stage designers in Bologna. In any event, many of his prints, especially his most famous — the ‘Carcieri’ (prisons) series — show how strongly he was influenced by them, whether student or not.

His early drawings from 1740 or shortly after, in which massed ranks of columns are used as decoration rather than to represent load-bearing structures, are more Bibienesque stage design than architecture. Already, there is the fascination with perspective trickery that sometimes prefigures the work of the Dutch graphic artist Escher in presenting logical impossibilities as convincing truths.

Unlike other Venetian artists, who went abroad when the supply of Grand Tourists dried up during the wars of the 1740s and 1750s, Piranesi remained in Italy, making much of his career in Rome, where he first went as part of the entourage of the Venetian ambassador in 1740.

When he settled in Rome in 1747, it was as the agent of a Venetian publisher, which allowed him to work on the first series of his own prints, the ‘Vedute di Roma’. These appealed to local patrons, as well as to Grand Tourists. They were followed by the ‘Antichità Romane de’ Tempi della Republica’ in 1748 and the ‘Carcieri’ in the two following years.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Piranesi’s Roman prints fully established his international reputation, which was such that, in 1757, he was elected an honorary fellow of the London Society of Antiquaries. With sound commercial sense, towards the end of his life he travelled south to exploit international interest in the excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii and the temples at Paestum.

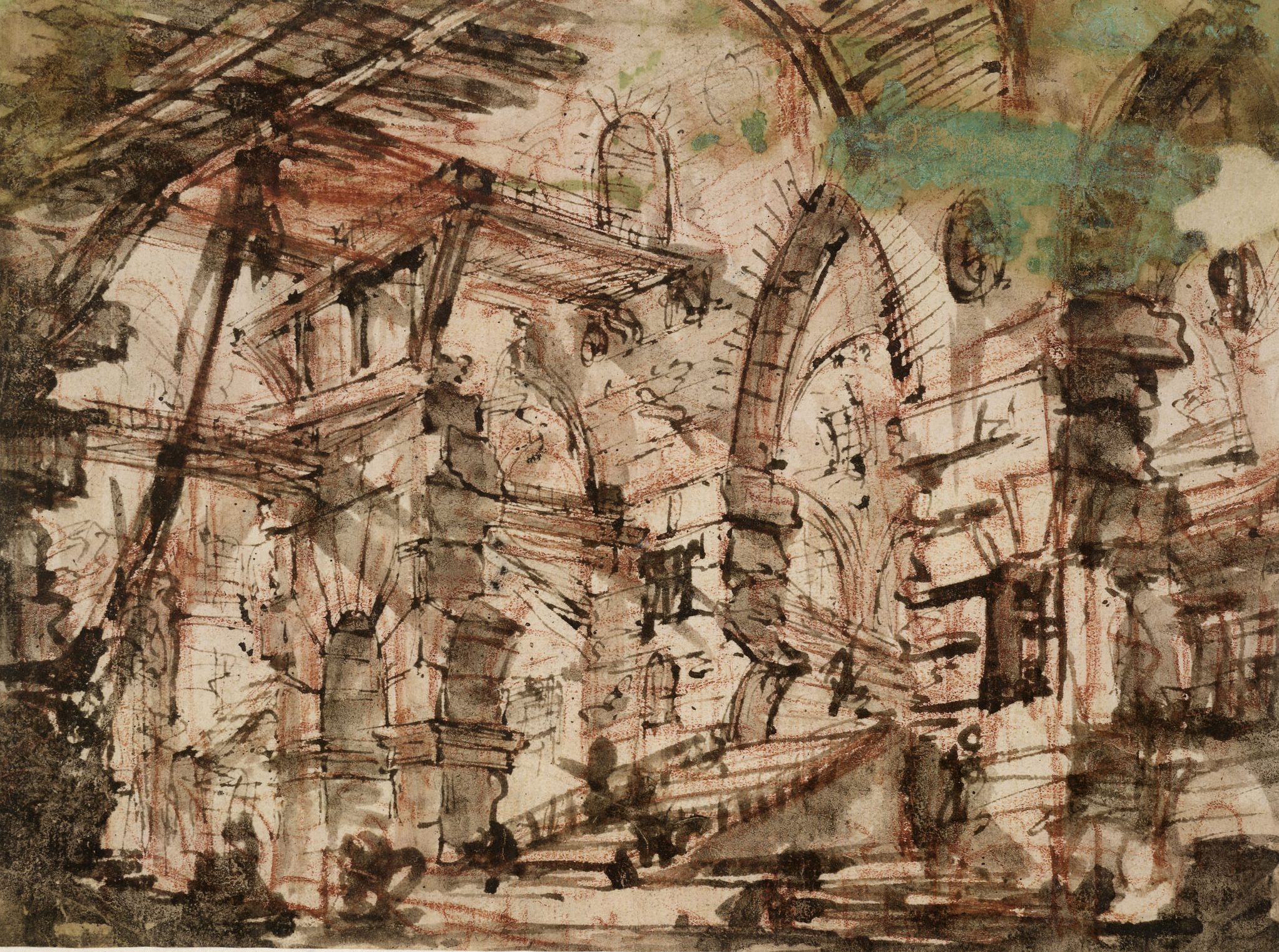

He drew compulsively through-out his life, using his sketches as a way of exploring and inventing. Many are studies for elements found in the prints, but, as Sarah Vowles, the British Museum’s curator of Italian drawings, says in her admirable catalogue, Piranesi did not follow the usual printmaker’s practice of making precise preparatory drawings.

He defended this with some exasperation: ‘Can’t you see that if my drawing was finished, my plate would become nothing but a copy; while if, on the contrary, I create the final effects on the copper, I’ve made it an original?’ In this working on the plate, Piranesi followed the masters that he revered, Rembrandt, Castiglione, Callot and della Bella.

It is hard to discuss Piranesi’s mature drawings and prints without resorting to musical terms — dash, verve, vivacity, brio — so energetic are they. Often, they seem to be works of a moment, flurries of red chalk and brown-ink lines, splatters of brown wash creating monumental architectural fantasies that overwhelm the dashed-in figures. Sometimes, almost all the drawing is in the washes, heavily brushed on, producing effects similar to Alexander Cozens’s ‘blottesques’.

These iron-gall ink washes may have darkened and lost their subtlety and, in some cases, have almost burnt through the paper, but they are very powerful

and, where there has been an accidental splash of paint on the corner of a sheet, it only adds to the drama. In the prints, Piranesi displays extraordinary facility with the graver, creating violent chiaroscuro to similar mesmerising effect.

In 1908, the British Museum bought 46 Piranesi drawings at the Sotheby’s sale of the collection of John Gott, Bishop of Truro. Although there is no documentary evidence, they had probably been bought by Gott’s uncle, who had died in 1817 when making his Grand Tour. The drawings, which provide an excellent chart with which to navigate Piranesi’s career, are the subject of the British Museum’s exhibition ‘Piranesi Drawings: Visions of Antiquity’ — it’s closed at the moment, but will run until late August when the museum reopens.

‘Piranesi Drawings: Visions of Antiquity’ is at the British Museum (once re-opened) until late August — www.britishmuseum.org. A catalogue of the same name is published by Thames & Hudson and the British Museum (£20). Other recommended books include The Complete Etchings (two volumes, 1994) and The Mind and Art of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1978), both by John Wilton-Ely, and Studies in Honour of John Wilton-Ely by F. Nevola and others (2018)

In Focus: The Hogarth masterpiece which shows that sometimes you need to 'listen' to a painting

A small exhibition at the Foundling Museum focuses on one painting — an image that inspires Huon Mallalieu to reflect

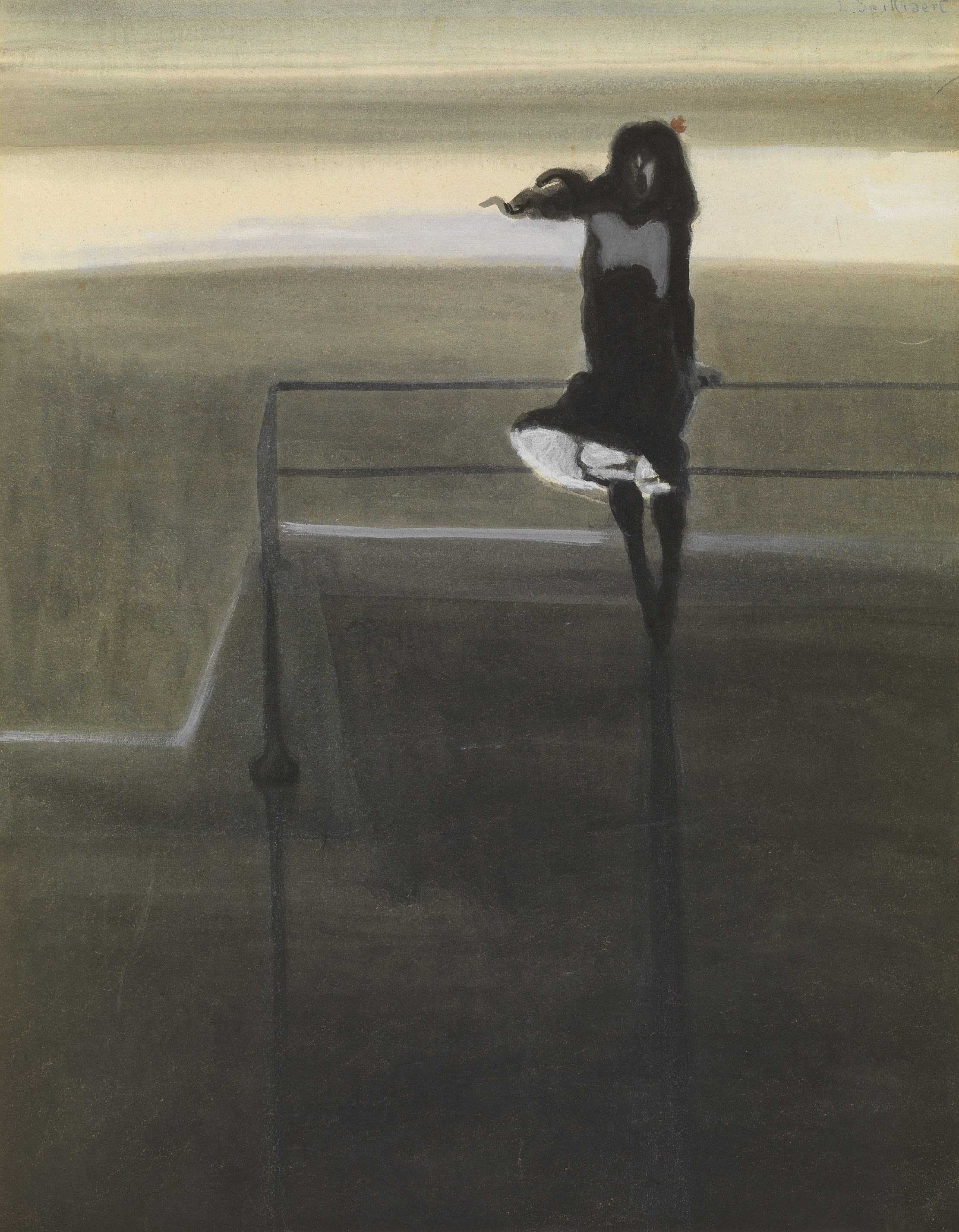

In Focus: The genius of Léon Spilliaert — 'If a ghost could paint, this is what it might look like'

Laura Gascoigne is enthralled by The Royal Academy's exhibition — available in virtual form on their website — focusing on Léon Spilliaert,

In Focus: The story of life of St Clare, and other restituted paintings that found their way back home

In Focus: The Heath Robinson Museum at Pinner, home to decades of gently satirised modern life

Huon Mallalieu tells the story of the small museum in Middlesex, where you'll find the last records of the county

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.