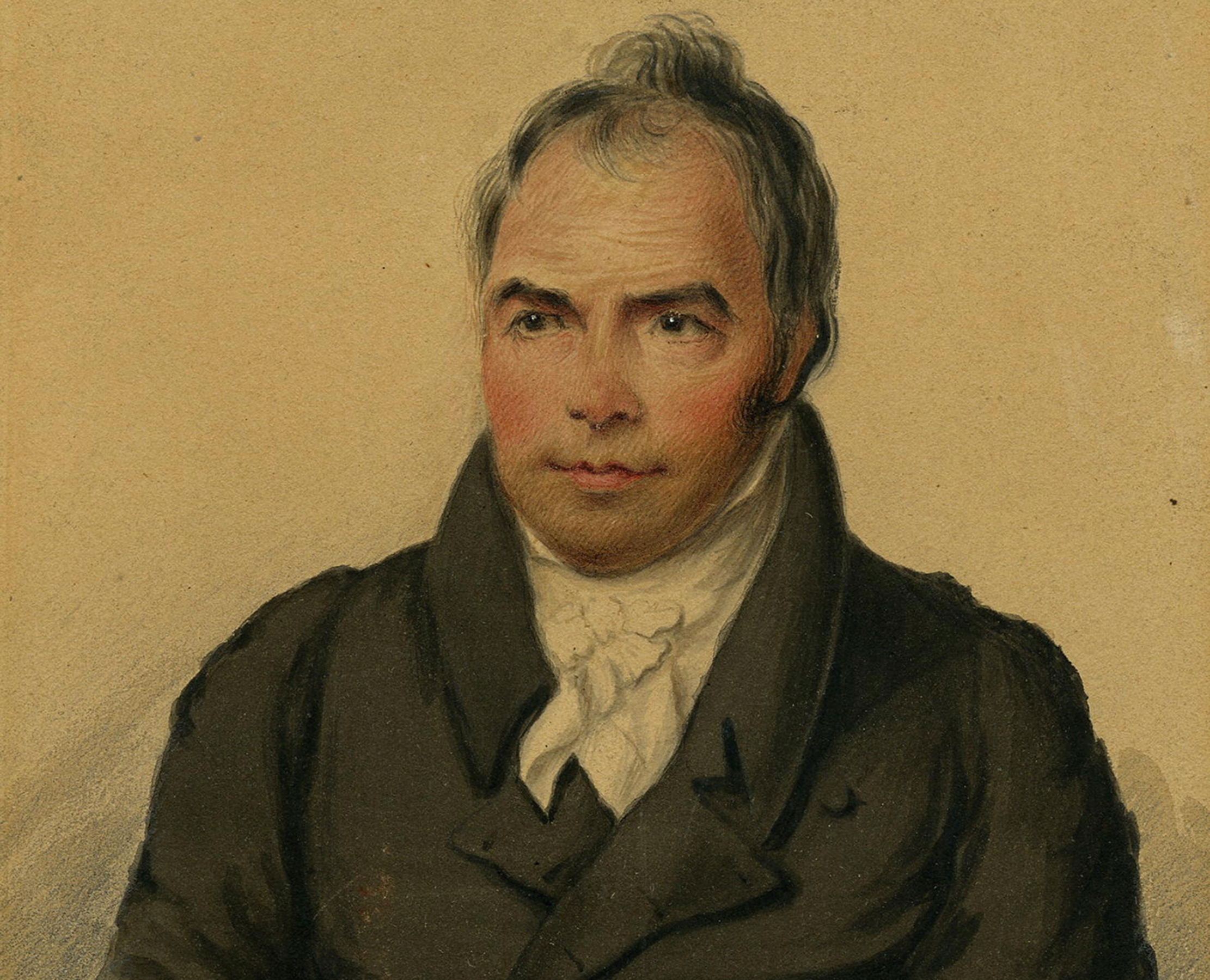

In Focus: John Croome, the 'mouse that roared' of the art world

Huon Mallalieu celebrates the bicentenary of John Croome, the enigmatic and oft-overlooked founder of the Norwich School of painting.

In 1863, 42 years after his death, Mousehold Heath, now in Tate Britain, was the first of John Crome’s works to be bought by a national collection. It caused something of a sensation, because although his reputation had been growing, it was still as a regional master rather than as one of the pre-eminent British landscape painters. Thereafter, Crome was bracketed with Gainsborough and Constable, both of whom, as it happened, were also East Anglians.

In 1974, when my first, distinctly lightweight, book was published, it was possible for me to ignore the claims of Bristol, Liverpool and elsewhere, writing that of the English regions ‘only Norwich is generally allowed to have produced a School’. That misapprehension did not long survive; soon, almost every corner of the country had its dictionary of artists. However, it can still be said that Norwich was the first to have an exhibiting society, and that its members produced one of the strongest and most coherent bodies of work.

Norwich and Norfolk were rich from sheep and cloth. The county was at the forefront of the Agricultural Revolution, which brought wealth, if at the expense of the peasantry excluded from common lands by enclosure. The city mercantile class blended into the surrounding country gentry, providing cultured patronage for local artists as they emerged.

Dr Edward Rigby, for instance, owned an apothecary’s shop where the 12-year-old Crome worked as errand boy, but he also experimented with agricultural innovations on his estate at Framingham, six miles from the city. Rigby had friends among the weaver-turned-banker Harvey and Gurney families, most importantly Thomas Harvey of Catton Hall, whose collection included works by Wilson, Gainsborough and Dutch masters, notably Meindert Hobbema.

Crome’s love of practical jokes is said to have included switching labels on medicine bottles, so Rigby will have been relieved when he moved on to an apprenticeship with a coach and sign painter. This was invaluable training, as he had to learn not only to paint, but to mix pigments that would be durable.

The son of a weaver, Crome was determined to become an artist and, when he was about 20, Harvey introduced him to Sir William Beechey, RA, who wrote later that he ‘was a very awkward, uninformed country lad, but extremely shrewd in all his remarks about Art’.

During the apprenticeship, he and his future brother-in-law Robert Ladbrooke, later a landscape painter of note himself, rented a garret studio. Once out of articles, Crome tried his luck in London, without much success.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

On his return, he founded the Norwich Society of Artists with Ladbrooke and turned to teaching, both private pupils, such as the daughters of the Gurney family, who took him on summer tours in England and Wales, and at Norwich School, where he remained for much of his life. He went abroad only once, to Paris in 1815 — Crome died, as he was born, in Norwich, a true son of Norfolk: one of the Broads is named after him, as is an area of Norwich City.

He was evidently an excellent teacher, which was his luck and his reputation’s misfortune. He encouraged pupils, including two of his sons (leading to his designation ‘Old Crome’), to copy his paintings; as he rarely signed, this has led to many misattributions. As Crome’s fame spread, he was also enthusiastically faked. His figures can be awkward, but his landscapes are masterly. Although they were deeply influenced by the Dutch masters Crome so admired, as W. F. Dickes wrote in 1905: ‘No one yet mistook a Crome for a Hobbema.’

‘A Passion for Landscape: Rediscovering John Crome’ is at Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Norfolk, from May 17–September 5 — www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk/norwich-castle

In Focus: The incomparable photography of Helmut Newton

Photographer Helmut Newton enjoyed a glittering career that blurred the lines between fashion, photography and art; as his centenary approaches

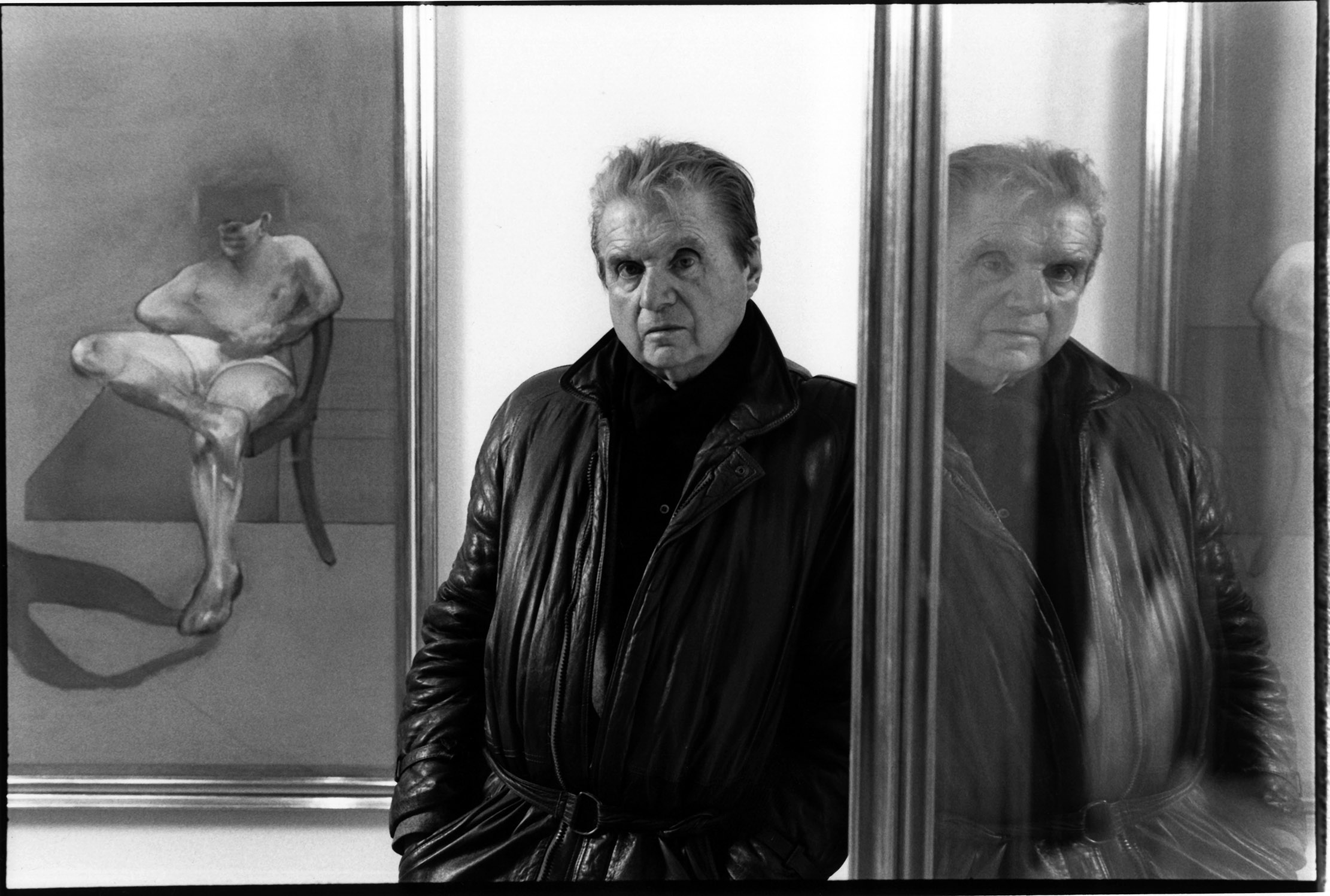

In Focus: The animalistic artworks of Francis Bacon

Martin Gayford considers the importance of snarling creatures, human and otherwise, in the art of Francis Bacon.

In Focus: The art of Ford Madox Brown

Known for his bold and thoughtful pictures, as well as a fondness for magenta, Ford Madox Brown was one of

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.