In Focus: James McNeill Whistler, the American in London who 'flung a pot of paint in the public's face' and turned art upside down

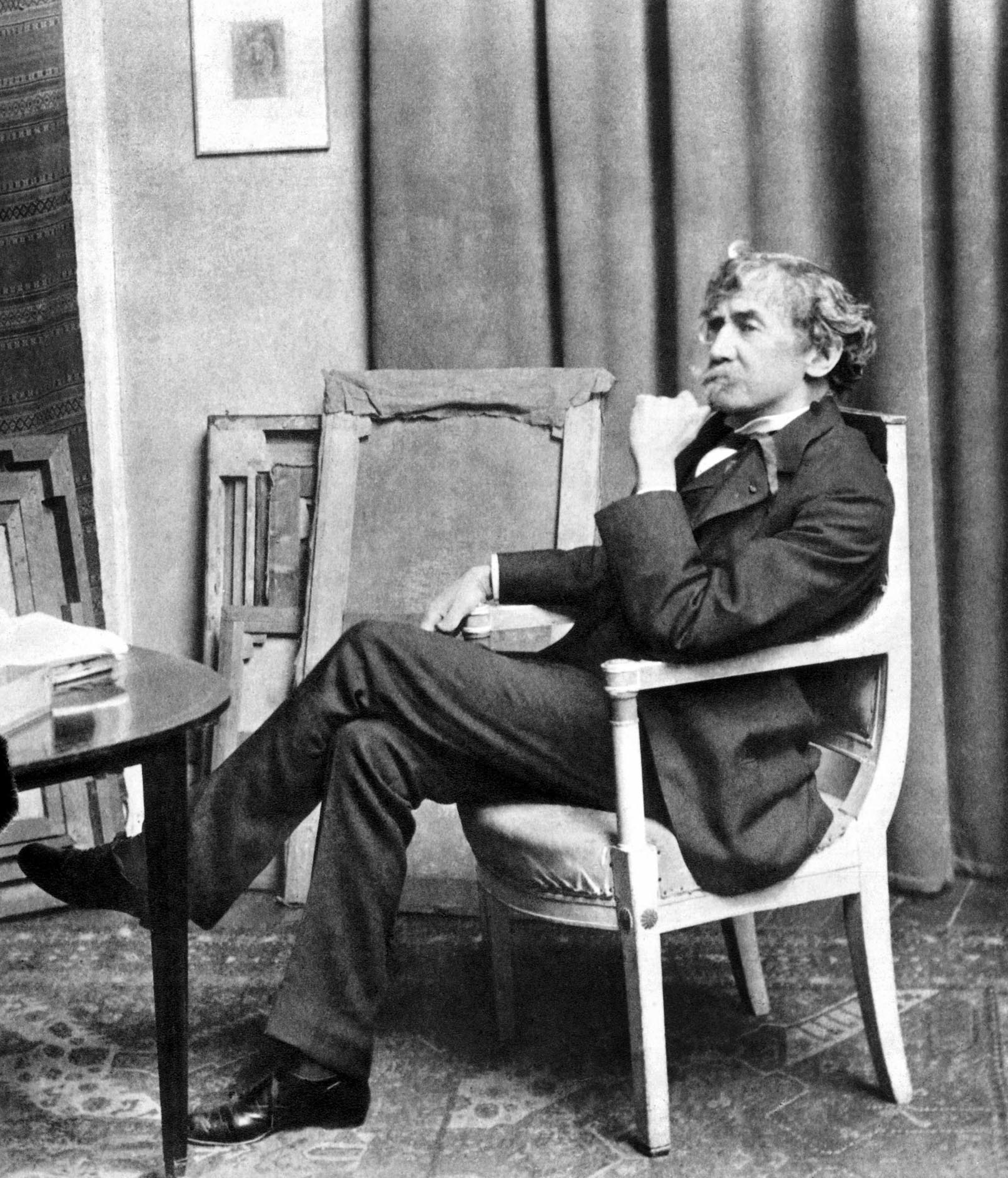

Short and slight, monocle-wearing James McNeill Whistler was a dashing, combative character who sought parallels between music and painting, says Caroline Bugler.

In 1878, an extraordinary trial took place at the Old Bailey — one concerned not with crime, but with the very nature of art itself. The eminent critic John Ruskin had published an open letter the previous year in which he accused James McNeill Whistler of ‘Cockney impudence’ for having the temerity to ask 200 guineas for ‘flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face’. The canvas on which the pot of paint had allegedly been flung was Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, which had gone on display at the newly opened Grosvenor Gallery in London. Whistler sued Ruskin for libel and won, although the award of one farthing damages did little to stave off his bankruptcy.

Whistler — who is the subject of a new exhibition at the Royal Academy — declared that his aim had been to ‘bring about a certain harmony of colour’, rather than to paint a particular subject. His evocation of fireworks exploding against the night sky may have been inspired by a scene he had witnessed over Cremorne Gardens on the Thames, but it could be taking place anywhere. The painting also looked unfinished, more like a sketch when compared with the painstaking execution of the highly detailed pictures by artists such as Edward Burne-Jones or William Powell Frith, to which the Victorian public was more accustomed.

Whistler’s journey to the point where he was obliged to defend his artistic philosophy in a courtroom had taken more than two decades. American by birth, he had a peripatetic childhood, moving from his birthplace in Massachusetts to St Petersburg in Russia, where his father worked on the railway, to London and back to Connecticut. His family wanted him to pursue a career in the priesthood or the military, but he had no religious vocation and a spell at America’s West Point Academy made it clear that he was not cut out to be a soldier. A gifted draughtsman, he was determined to be an artist.

In 1855, at the age of 21, Whistler decamped to Paris, where he began his artistic training in earnest. Short and slight, with dark curly hair and a monocle, he cut a dashing figure. Cultivating a ‘French’ dandified appearance and sporting a stovepipe hat with a wide brim, he fully embraced bohemian life and French café society. His circle of friends included some of the leading avant-garde artists of the day, such as Gustave Courbet and Edouard Manet, and the poet Charles Baudelaire. Their belief in the importance of depicting the modern world struck a chord with him.

Whistler took up etching, a medium he felt ideally suited to representing life in the modern city. After he made London his permanent home in 1859, he created an astonishing series of prints of the Thames at Rotherhithe, Limehouse and Westminster, portraying all the bustle and commerce of the river: bridges, untidy wharves, warehouses and police going about their business. He also produced an oil painting of Wapping, of a prostitute and her pimp negotiating a sexual deal with a sailor, set against a busy river scene. It was a variation on the popular subject of the fallen woman, yet without the moralising intention a Victorian audience familiar with the novels of Charles Dickens or Pre-Raphaelite art might have expected. Gradually, however, the narrative element became less important in Whistler’s work as he became more interested in painting pictures that could be admired for their own sake rather than for what they depicted — what his friend the poet Algernon Swinburne termed ‘art for art’s sake’.

When Whistler exhibited Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (1862), he insisted that it was nothing more than ‘a girl dressed in white standing in front of a white curtain’. However, many critics could not resist attempting to construct a story around it, some suggesting that it represented a bride whose husband was snoring behind the curtain and others linking it to Wilkie Collins’s novel The Woman in White. A portrait of a striking flame-haired woman, it was rejected by the jurors of the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition, although it was shown in a private gallery and eventually received a more positive reception when it went on display in Paris in the Salon des Refusés, alongside paintings by progressive artists, including Manet.

The model was Joanna Hiffernan, Whistler’s mistress, muse and friend for many years, who played a central role in his life and art, even after her romantic liaison with him ended, and featured in several other paintings, too. In The Little White Girl (1864), she is shown again in a white dress, staring wistfully into an overmantel mirror. Here, she clutches a Japanese fan: Japanese accessories were soon making a regular appearance in the artist’s work, reflecting the craze for all things Oriental that was sweeping Europe. Yet Whistler’s appreciation of Japanese art went far deeper than the appropriation of objects: it began to influence his own compositions. The Japanese woodblock prints flooding into Europe at the time often showed gatherings of beautiful women in flowing robes in languorous poses and, in response, Whistler produced several scenes of elegant ladies relaxing on balconies or draped across sofas, sometimes holding parasols or in kimonos.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

There was also a distinctly Oriental flavour to his major commission of 1877: to decorate the dining room in the London home of his patron, shipping magnate Frederick Leyland. The Peacock Room, now preserved in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington DC, is an exuberant blue-and-gold colour scheme featuring peacocks and shelves filled with Oriental porcelain. One of Whistler’s Japanese-inspired works, La Princesse du Pays de la Porce-laine, has pride of place over the fireplace.

The picture is a portrait of Christine Stillman, sister of a Pre-Raphaelite artist. As were many of those who sat for Whistler, she was part of his circle, but he also received commissions from aristocrats, literary and theatrical figures. His subjects had to endure long and painful sittings (one described the experience as ‘drawing the life from him’). The artist described his likenesses in similar terms to his landscapes as ‘arrangements’ of colour, although many are arrangements in monochrome, dominated by black.

None is more famous than the portrait he painted of his mother, an exercise in tonal harmony described as Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1 (1871), which shows the sitter in profile, seated, dressed in black and against a grey wall, the whole enlivened with the white highlights of her bonnet, handkerchief and the white mount of the picture on the wall. Whistler may have downplayed the emotional significance of the painting, but it has morphed into an icon of motherhood.

In many ways, Whistler is a paradoxical artist — a creator of serenely beautiful works designed to create an impression of effortlessness, but which were the result of intense and lengthy aesthetic contemplation. His personality, like his work, was carefully constructed, yet he had a quick wit and relished his role as a provocateur, enjoying sparring matches with his friend and sometime rival Oscar Wilde. He cultivated a position as an outsider, but enjoyed hosting social gatherings where he could shine brilliantly.

In the decade following Whistler’s death in 1903, the brilliantly coloured Fauve canvases of Matisse and Derain, the Cubist works of Picasso and Braque and the dynamic paintings of the Italian Futurists shook up Europe’s avant-garde scene. These iconoclastic art movements echoed the anarchy and fractured experience of the modern world, but Whistler’s elegantly refined works continue to provide a powerful antidote to it.

‘Whistler’s Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London W1, until May 22 — 020–7300 8090; www.royalacademy.org.uk

The life and times of James McNeill Whistler

July 11, 1834 — Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, US, to Anna McNeill Whistler and George Washington Whistler, a railway engineer

1843–48 — Lives in St Petersburg, Russia, where his father is working on the Moscow railroad. Attends drawing lessons at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts

1851 — Enrols at West Point Military Academy

1855 — Goes to Paris to study art

1859 — Moves to London, but continues to visit and exhibit his work in Paris. Produces the ‘Thames Set’ of etchings

1860 — Exhibits his first painting in London. Joanna Hiffernan becomes his mistress and model

1863 — The White Girl is exhibited in Paris. Whistler’s mother comes to live with him in Chelsea

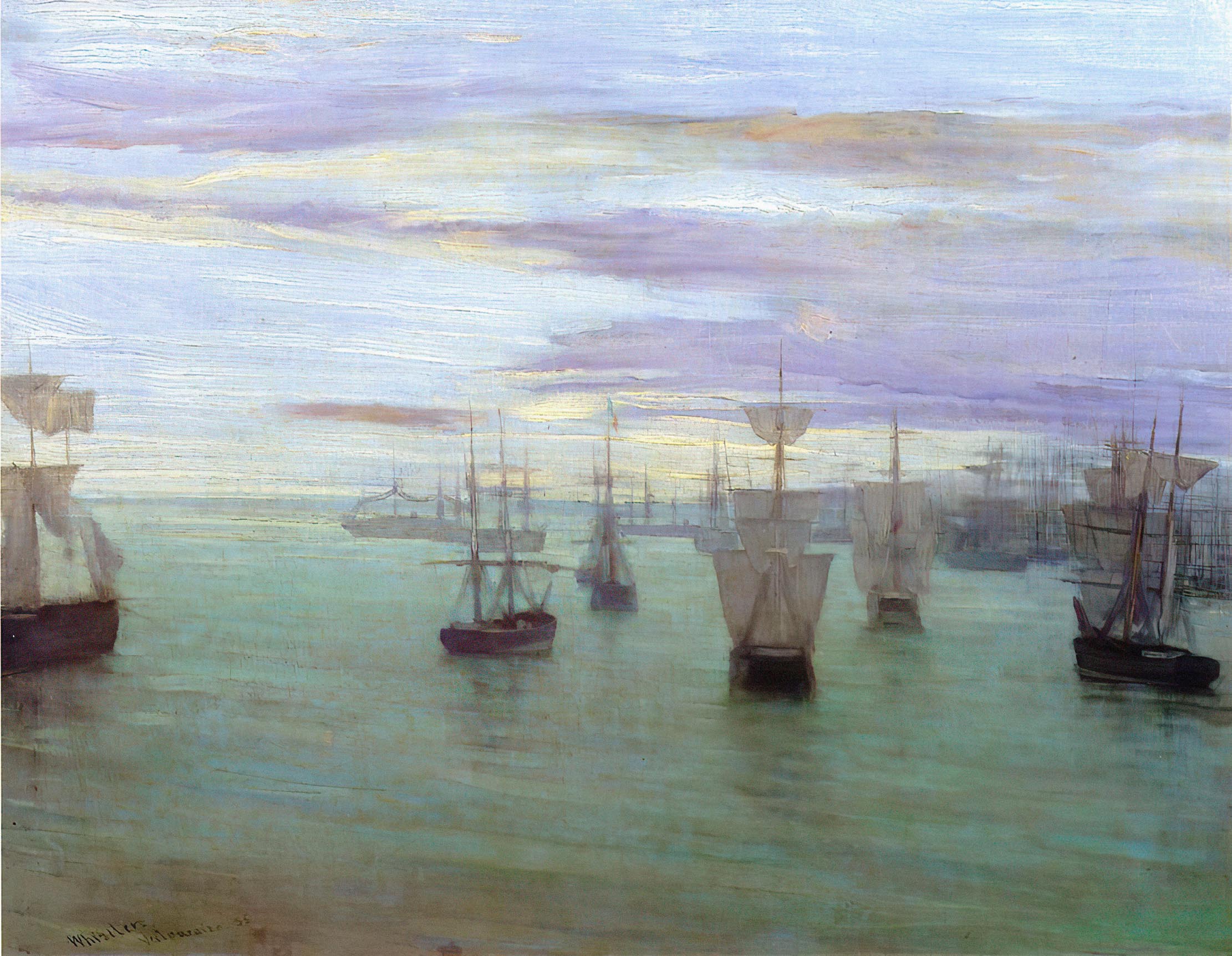

1866 — Travels to Valparaiso, Chile, and begins his ‘nocturnes’

1871 — Returns to painting portraits

1873 — Maud Franklin replaces Hiffernan as Whistler’s chief model and mistress

1877 — Completes the Peacock Room for F. R. Leyland

1878 — Court case against Ruskin for his criticism of The Falling Rocket

1879 — Is declared bankrupt. Goes to Venice, Italy, where he produces a set of etchings

1885 — Delivers the Ten O’Clock Lecture expressing his belief in ‘art for art’s sake’

1880s–90s — Shows work in exhibitions all over Europe and is critically acclaimed

July 17, 1903 — Dies in London

Whistler's marriage of art and music

Towards the end of the 1860s, Whistler began to turn his back on realism in art. He still depicted cityscapes, but was no longer motivated by a desire to reflect gritty urban reality, preferring instead to veil ugly industrial details in tranquil night scenes. He lived near the Thames and, for his London riverscapes, he ventured out in a boat after dark and committed the visual spectacle to memory before producing the paintings back in his studio. The resulting canvases are pervaded by a softly diffused mist that seems to dissolve forms. Their colour palette is limited with muted tones, bringing to mind a dreamy or pensive mood. Some of these simple compositions evoke the Japanese woodblock prints of Hiroshige. Whistler called these paintings ‘nocturnes’, emphasising the link he felt between painting and music.

‘By using the word “nocturne”,’ he explained, ‘I wished to indicate an artistic interest alone, divesting the picture of any outside anecdotal interest which might have been otherwise attached to it. A nocturne is an arrangement of line, form and colour first.’

Credit: Getty Images

In Focus: John Hassall's iconic travel posters

The works of British poster king John Hassall remain a breath of fresh seaside air, says Lucinda Gosling.

In Focus: Why the eerie thrives in art and culture

The tradition of ‘eerie’ literature and art, invoking fear, unease and dread, has flourished in the shadows of British landscape

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

In Focus: Bernardo Bellotto, the Canaletto of the North

Being the nephew of Antonio Canaletto was both a blessing and a curse for Bernardo Bellotto, whose brooding landscapes eventually

In Focus: How an amateur gardener created Sissinghurst, one of the most influential gardens ever made

'No garden had greater influence in the second half of the 20th century' according to John Sales, the National Trust's

In Focus: The vast trove of watercolours documenting the world as it looked before photography

The explosion in watercolour painting in the 18th century came not from artists' studios but rather from the unbeatable practicality

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.