In focus: How galleries and art dealers have shifted to showing and selling online

Galleries and dealers are using the difficulty of the lockdown to showcase their wares in virtual forms, from wartime oils to a cleaning lady and a Turk.

With no fairs to preview for who knows how long and no physical exhibitions to flag up or review, I shall devote some of these lockdown columns to show the various ways that the art trade is offering its wares and services on the internet.

I shall also take opportunities to look back at the changes in markets and fashions during the 60 years since I first ventured into junk shops, galleries and salerooms as a schoolboy.

Of course, art and antiques traders have been using the internet to advertise themselves for some time, but not all have exploited it as effectively as they might. Many rightly feel that it is still generally best to examine a work of art physically before buying it. Even when one has a catalogue, it is all too easy to make a careless mistake.

Leaning against a wall across the room from me is a watercolour for which I made a post-sale bid from the catalogue when it had been bought in. I was so pleased with myself for recognising the artist when the auctioneer had it merely as English School that I failed to check the measurements. It is too big and heavy for me to hang anywhere.

Some things — small bronzes for instance — demand to be held in the hand. When assessing a chair, furniture dealers will immediately examine its underside and the first rule for buying a picture is: look at the back, which may tell you as much as the front. However, even if technology can never eliminate human fallibility, or render the eye and hand redundant, it forges on and virtual exhibitions are a great advance on photographs, in whatever form.

Dealers that have been exploiting the possibilities for some time include John Bly (www.johnbly.com), the fifth-generation furniture dealers established at Tring in Hertfordshire since at least 1891, and Abbott & Holder.

Bly’s monthly internet newsletter presents stock and acquisitions effectively and offers wisdom culled from long experience. Abbott & Holder put its much-enjoyed lists of reasonably priced watercolours on line some time ago, with the advantage that everything could be illustrated. I don’t expect that there have been many complaints from clients.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As mentioned last week, the Open Art Fair launched at Duke of York Square in the King’s Road, but closed on the second afternoon. However, there was just time for technicians to video the eerily unpeopled stands, so it continues to have a ghostly run on the web. Only one or two items are highlighted on each stand, but it is very easy to link to the exhibitors’ own websites and this may offer some relief to itchy shopping fingers.

No doubt suggested by constant references to the Second World War in comments on our present situation, two wartime paintings particularly caught my attention. Rountree Tryon Galleries (www.rountreetryon.com) have a 32½ by 52¼in doodlebug’s-eye view of defence batteries on the Kent cliffs by Frank Salisbury (1874–1962), a remarkable man who was the son of a plumber and became a successful society portraitist.

A very different product of the same year, 1944, with Strachan (www.strachanfineart.com) is the 19¾in by 23½in Portrait with Pears by Michael Ayrton (1921–75), a still under-rated artist. The sitter was Mrs Fursey, cleaning lady at Camberwell School of Art, where Ayrton was teaching, having been invalided out of the RAF.

Another exhibitor at the truncated fair, Guy Peppiatt, was also about to hang an exhibition of British portrait and figure drawings. Since he put it online a week ago, he has sold 15 of them. Yet to find a buyer (as I write) is a particularly sensitive 9¾in by 8¼in black-and-white chalk by John Downman (1750–1824), depicting the head of The Turk who travelled with Mr West through Italy.

A London gallery that has been quick to put its exhibition programme online is Lyndsey Ingram, in other circumstances of 20, Bourdon Street, W1. Over the coming months, the gallery will offer a series of virtual shows, creating an ‘experience that will ensure continuity for the gallery’s programme and provide a dynamic platform where our artists’ work can be seen and enjoyed online’.

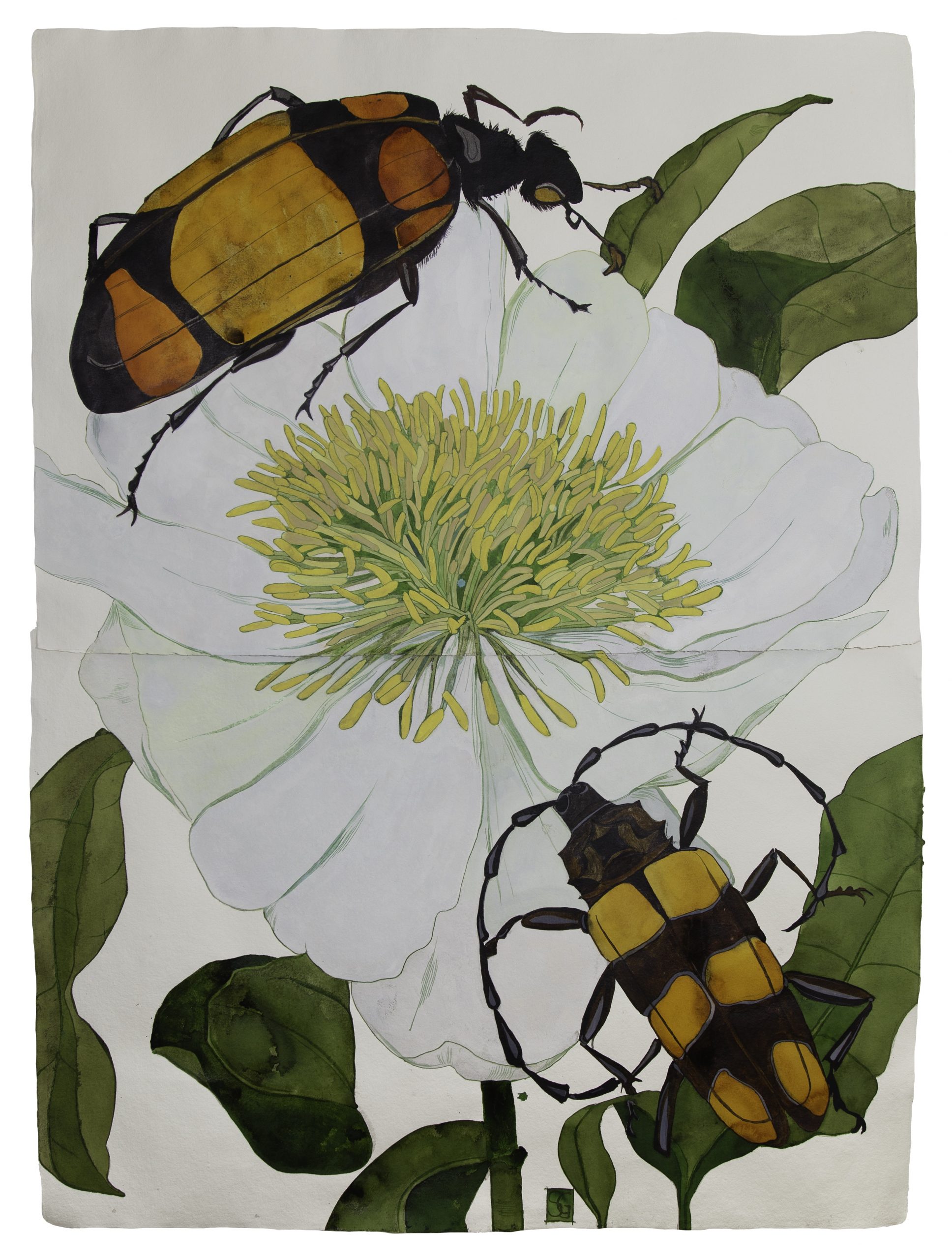

Until April 10, the exhibition is Georgie Hopton and Gary Hume’s ‘Hurricanes Hardly Ever Happen’. This will be followed by Tom Hammick’s ‘Atlantica’, from April 14 to 24; prints by David Hockney, from April 27 to May 8; Suzy Murphy’s ‘Harbour Island’, from May 11 to 22; and new work by Sarah Graham, from May 25 to June 5. The last is a new artist to me and I think her botanical drawings in ink washes, such as Paeonia emodi II, are magnificent.

In what may be a first, Messums Wiltshire has produced a video shot entirely by drone to take us around the current show in the magnificent tithe barn, ‘Beyond the Vessel: Narratives in Contemporary European Ceramics’. It is an enticing introduction and a price list is on the site.

The show has been seen by 40,000 people in Istanbul and features 11 artists from nine countries: Sam Bakewell, Giampaolo Bertozzi and Stefano Dal Monte Casoni, Claire Curneen, Christie Brown, Phoebe Cummings, Bouke de Vries, Kim Simonsson, Jørgen Haugen Sørensen, Carolein Smit, Malene Hartmann Rasmussen and Vivian van Blerk.

As a reminder of the reach of traditional print, I cannot resist printing a recent communication from the Modern British dealer Freya Mitton: ‘In April 2018, you featured in Country Life a work by Mary Fedden which I was planning to take to the CADA Fair at Blenheim Palace.

Needless to say the picture never made it to Blenheim. It was bought straight from the photograph by a famous model from the 1970s. When I arrived to deliver it, I found a truly wonderful collection of Modern British Art and that week’s copy of Country Life left open at the relevant page.’ This was the 14½in by 22in watercolour The Pineapple (Red Still Life), which is happily illustrated at the top of this page.

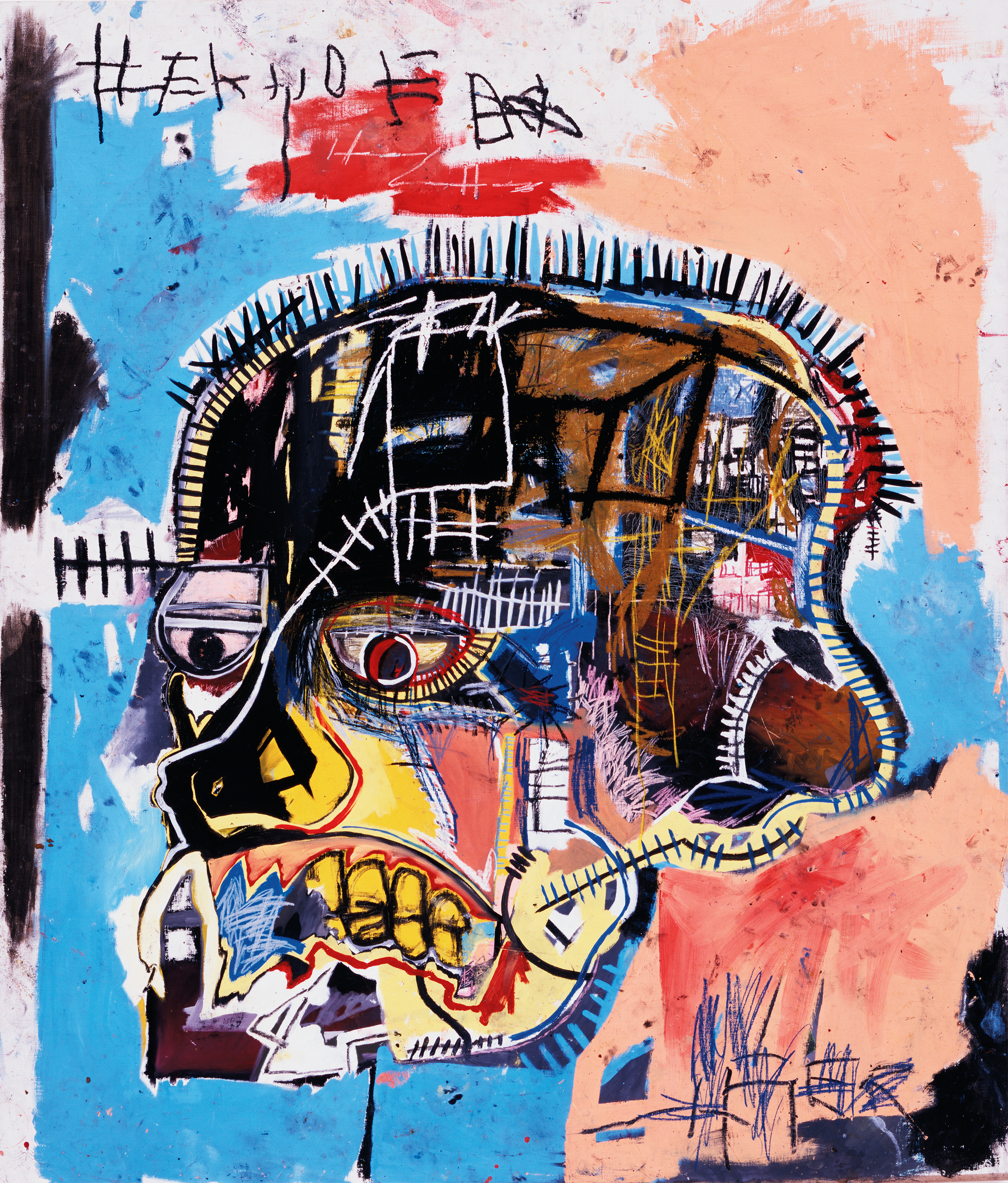

My favourite painting: Martin Waller

Martin Waller, the co-founder of design boutique Andrew Martin chooses a raw image by one of New York's most powerful

In Focus: How British artists contributed to the uncanny, desirous world of Surrealism

Michael Murray-Fennell delves into the subconscious, the uncanny, war and desire and discovers the contribution made by British artists to

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.