In Focus: How the 'Tottering Hall' cartoonist became a sculptor

Best known as the creative force behind Dicky and Daffy, it was her son’s death that prompted Annie Tempest to learn ‘the grammar of the sculptor’s language’, discovers Ian Collins.

Annie Tempest’s cartoon strip in Country Life has long been the reason why, as the late Duke of Devonshire noted, many of us read magazines backwards. Tottering-by-Gently good humour from a rarefied world also resonates as wry comments on universal life—but, for the artist-author, it’s all deeply personal.

As is now well known, Lord ‘Dicky’ Tottering is largely modelled on Annie’s father and Lady T (Daffy) partly on herself. Tottering Hall is really Broughton Hall, near Skipton in North Yorkshire, seat of the Tempests since 1097—a recent transformation from gin palace to wellbeing sanctuary ripe for fresh lampooning.

One character in this ever-evolving caricature will remain 18 forever. He is based on Annie’s son Freddy, who died from an accidental heroin overdose in 2011. Country Life’s resident cartoonist has not missed a single week in cheering up the nation since she arrived in 1993, but some things are beyond a joke: the death of a child is almost beyond imagining.

In shattering depths of grief, a stricken mother picked up the pieces in plaster, ceramic, mosaic, glass-cast resin, stone and bronze, rescuing and reinventing herself as a sculptor. Ideas exploded as she grappled with the feelings she needed to express.

Now, she has found her innermost voice in quicksilver bronze portraits of conductors and dancers. More than records of performance, these abstracted figures form a salute to vitality. Capturing concentration and movement, they celebrate those moments when we are fully and fabulously alive. ‘Viewers can add their own narrative,’ the sculptor says. ‘Where have you found passion in your life that affected every fibre of your body in that electric way?’

The second of five children, she and elder sister Bridget were born in Zambia. The family returned to England, in 1962, when Annie was two years old. She has no memory of infancy in Africa, but sees it—through 40 almost-annual visits to Kenya—as her spiritual home.

Her father, Henry, was a second son in a clan bound by rules of primogenitor favouring first-born males. Uncle Stephen, autistic and alcoholic, went a step further and kicked out his relatives when he inherited Broughton Hall on his 21st birthday. Henry did whatever he could to make a living, trying his luck in Africa and meeting his wife, Janet, at the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute in Rhodesia.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Back in England, the penniless Tempests were taken in by a great-aunt who presided over Kirtlington Park, a Palladian country house in Oxfordshire parkland landscaped by Capability Brown.

‘We lived like vermin in the cellars,’ Annie remembers. ‘Ejected from our windowless basement each morning, we became feral children. I created a home for myself in a blackberry bush.

‘I was also dyslexic, so was taken out of school and sent for lessons with a woman in the village. Lessons were limited to how to play whist, count money and name wildflowers. As art was Bridget’s territory, I didn’t really start drawing until I was 24.’

Uncle Stephen finally lent his younger brother some money so the cellar dwellers could build a small house in a corner of the Kirtlington estate, Annie helping to lay the foundations. When the lender died unexpectedly, her father inherited Broughton Hall—plus vast debts. Life in the ancestral pile was hellish: tadpoles swam from taps and snow lay on the billiard table. They usually dressed for dinner by donning hats, coats and gloves to brave the freezing dining room.

‘How dad saved the estate and passed it on to my brother is a miracle,’ Annie reflects. ‘Luckily, Roger is an entrepreneur and he has done a brilliant job.’

It was always brutally clear that Tempest daughters would have to make their own way. Annie became a medical secretary in London, typing and filing, but also watching operations and learning anatomy—an ideal foundation for a figurative sculptor.

Drawing on a comic gift and untapping a talent for illustration, she created a book called How Green Are Your Wellies? This led to two successive cartoon series in national newspapers and an award as Strip Cartoonist of the Year. Then, she switched to Tottering-by-Gently and her natural home in Country Life. In 2009, the Cartoon Art Trust gave her the Pont Award for portrayal of the British character. Now, with a 40-year career, she may be the Hogarth of our day.

Marriage to the composer James McConnel, in 1991, produced two children, Freddy and Daisy, and a move to Norfolk. James made a gripping television documentary suggesting that Mozart suffered from Tourette’s syndrome, as he did himself. Or, as Annie put it: ‘James has Tourette’s and we suffer from it.’ They divorced in 2006, but remain friends.

Freddy McConnel, a musical prodigy, table-tennis champion and Mensa member (IQ 144), also had Tourette’s. With an addictive personality, he was secretly smoking and drinking from the age of nine. Five years later, he was hooked on hard drugs and his family was doing everything possible to unhook him, via specialist centres in Oregon, US, South Africa and The Priory rehabilitation clinic in Essex. Hopes of reprieve ended when Freddy overdosed after a heroin relapse.

As she turned to sculpture to process the enormity of mourning, Annie was invited to make the statue of Amy Winehouse outside the Roundhouse, London NW1. Her grief was too raw. Instead, she made for her garden a life-sized statue of Freddy wearing his favourite shroud-like Moroccan djabella—an image of infinite peace.

Creativity has been the artist’s path back to joy. She is immensely proud that daughter Daisy is now a prize-winning guitar-maker (www.tempestguitars.com), who sings and plays her own instruments. Meanwhile, Annie’s own life has never been richer. As she says: ‘Having learned the grammar of the sculptor’s language, I have finally moved into song.’

Annie Tempest’s sculptures are at Messum’s St James’s, Bury Street, London SW1 from May 4–27 (020–7287 4448; www.messums.com)

Like quicksilver: the sculpture of Annie Tempest

- The sculptor’s conductor began with one-finger iPhone drawings in the Royal Albert Hall, but she recalls neither his name nor the music. The point is to make the specific universal

- Carlos Acosta, the Cuban ballet star of Spanish and African heritage, was barely sketched in a darkened theatre. The key was a memory of energy

- Bending each little armature rapidly into shape, Annie breaks off when the roughest—purest—sensation is imparted in the elemental structure. Next, she rushes to the foundry she helped to set up on a nearby farm for a six-month, 20-part collaborative process with Wayne and Laura McKinney

- Digital innovation is eagerly embraced, but these bronze sculptures still rely on the ancient lost-wax process the maker learned with Samburu tribesmen in Kenya, using railway-line supports and bellows made from animal hide and lungs

- Now, with zest and curiosity ablaze, the artist is welding and trialling incinerator firing thanks to a mentor sculptor she met on Instagram, who lived as an Iron Age man for a year.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher

-

In Focus: How Italy inspired JMW Turner

In Focus: How Italy inspired JMW TurnerMary Miers considers how the country that fascinated Turner from youth shaped his artistic vision.

By Mary Miers

-

In Focus: Why the eerie thrives in art and culture

In Focus: Why the eerie thrives in art and cultureThe tradition of ‘eerie’ literature and art, invoking fear, unease and dread, has flourished in the shadows of British landscape culture for centuries, says Robert Macfarlane.

By Country Life

-

In Focus: John Hassall's iconic travel posters

In Focus: John Hassall's iconic travel postersThe works of British poster king John Hassall remain a breath of fresh seaside air, says Lucinda Gosling.

By Country Life

-

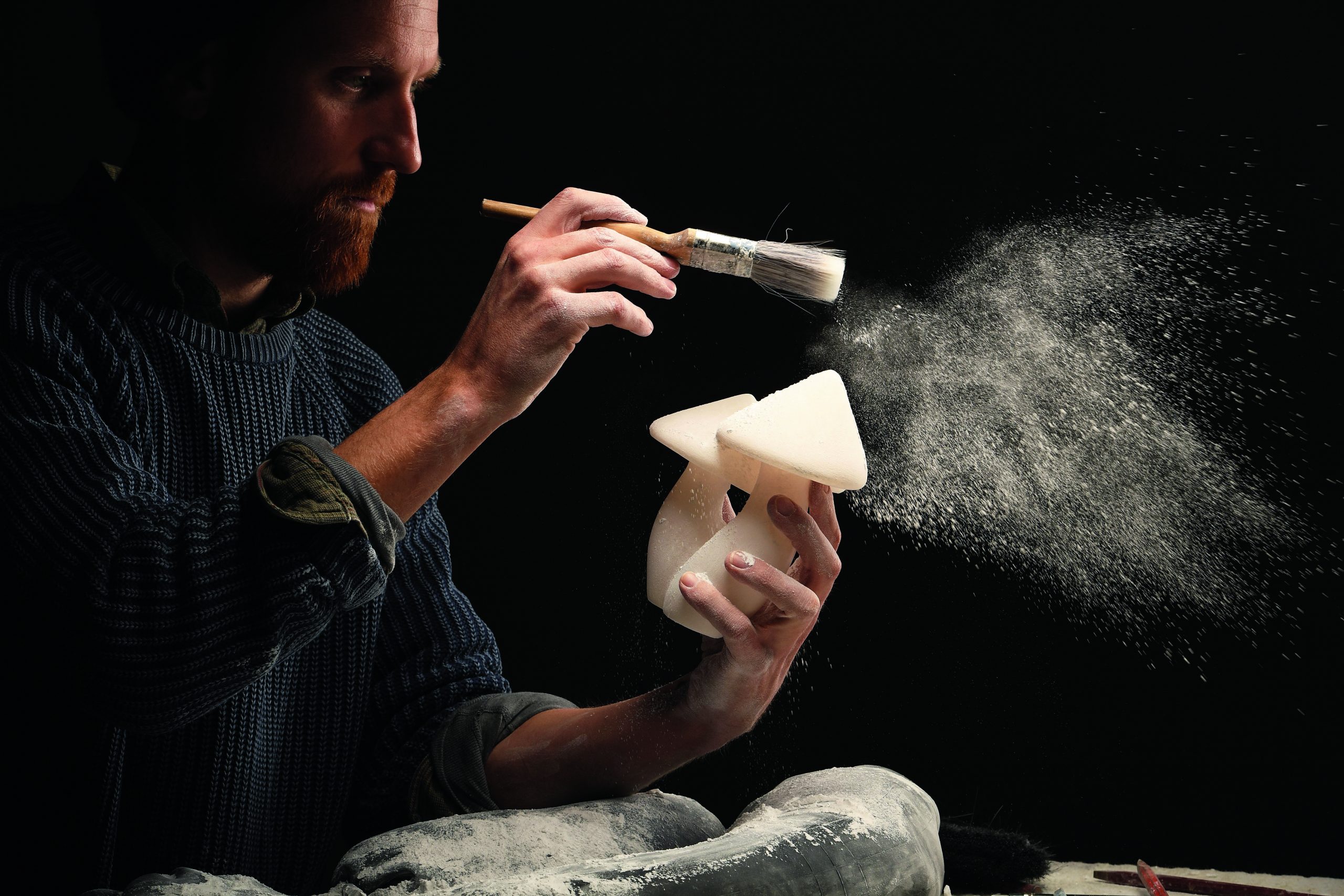

In Focus: the fungi sculptures that bend stone into soft, flowing forms

In Focus: the fungi sculptures that bend stone into soft, flowing formsThey may look as delicate and organic as the real thing, but Ben Russell’s sculptures of fungi, cacti and roots will outlast us all, believes Natasha Goodfellow.

By Country Life

-

In Focus: How 21st century artists are reviving the art of the fresco

In Focus: How 21st century artists are reviving the art of the frescoOnce practised by Michelangelo, Raphael and da Vinci, the art of fresco creation has changed little in 1,000 years. Marsha O’Mahony meets the artists following in their footsteps.

By Country Life

-

Why a good frame can be a work of art in its own right

Why a good frame can be a work of art in its own rightCatriona Gray retraces the history of frames, admires the craftsmanship required to make them and discovers what's the best way to preserve them.

By Country Life

-

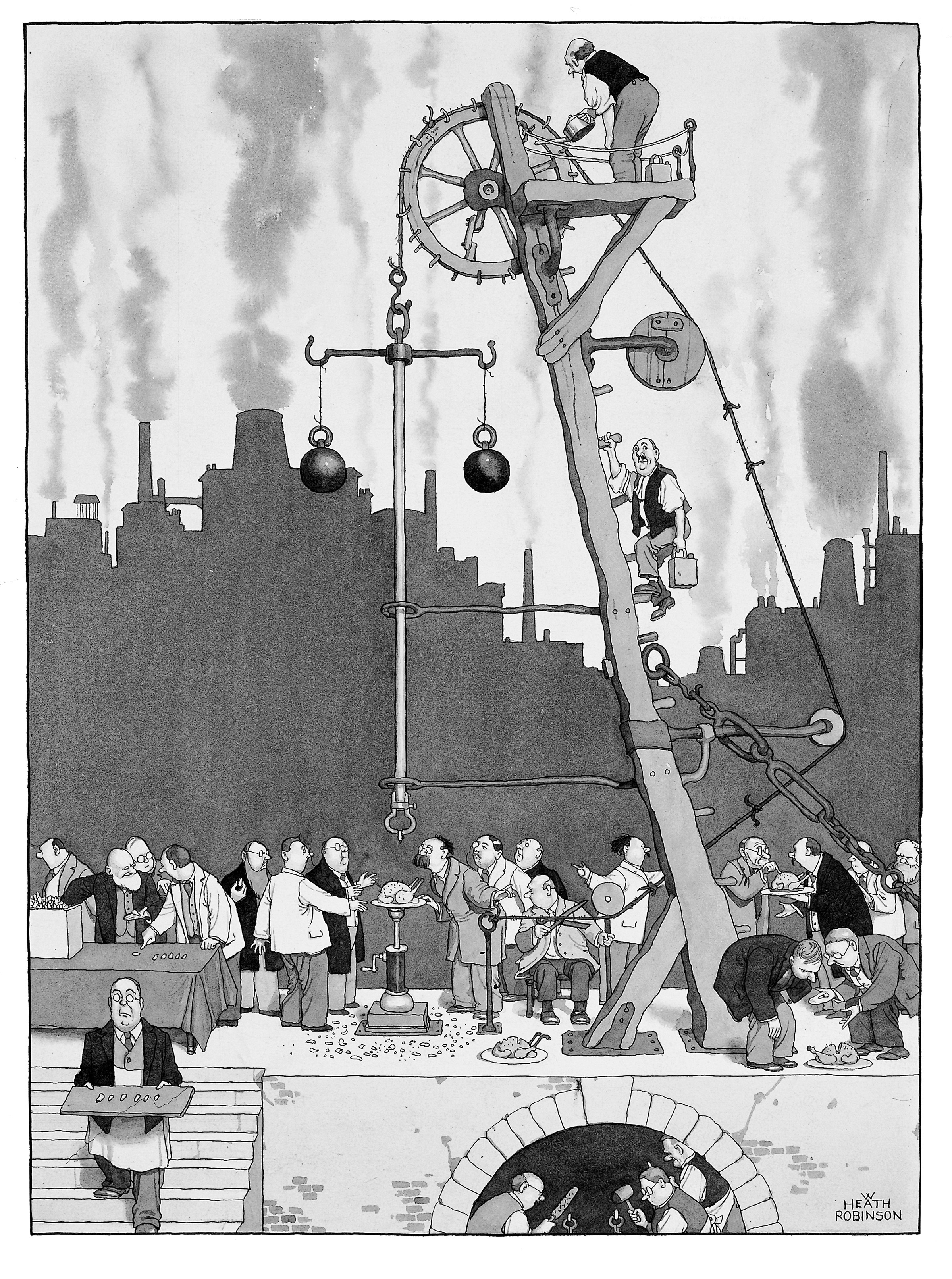

In Focus: The Heath Robinson Museum at Pinner, home to decades of gently satirised modern life

In Focus: The Heath Robinson Museum at Pinner, home to decades of gently satirised modern lifeHuon Mallalieu tells the story of the small museum in Middlesex, where you'll find the last records of the county before it became overrun by suburbia.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

In Focus: How British artists contributed to the uncanny, desirous world of Surrealism

In Focus: How British artists contributed to the uncanny, desirous world of SurrealismMichael Murray-Fennell delves into the subconscious, the uncanny, war and desire and discovers the contribution made by British artists to the Surrealist movement.

By Country Life