In Focus: How Rodin became not only the father of modern sculpture, but the first global celebrity artist

The Tate Modern's new exhibition on Rodin prompts Laura Gascoigne to revisit the extraordinary life and career of Auguste Rodin (1840–1917).

The must-see art exhibition at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, was the work of one man. Auguste Rodin had built his own pavilion in the Place de l’Alma and filled it not with finished bronze and marble sculptures, but rough plaster models looking like works in progress. The impression of entering an artist’s studio was enforced at the entrance by a nude plaster figure of Pierre de Wissant, one of The Burghers of Calais, with no head or hands.

The exhibition, which would cement Rodin’s international celebrity, was designed as a testament to his singular vision. He had always cast himself as an outsider. A humble police inspector’s son whose talent for drawing had won him a place at the Petite École for decorative arts, he failed three times to pass the entrance exam for the École des Beaux Arts — the classic route to a career in sculpture — and after his lover, Rose Beuret, gave birth to a son in 1866, he supported the family by taking ornamental work.

His own sculptures were far from ornamental, however. The plaster Mask of the Man with the Broken Nose he submitted to the Salon in 1865 was a rugged portrait of an odd-job man, Bibi, with no back to its head where the clay had fallen off before casting.

Unsurprisingly, the sculpture was rejected as unfinished, but Rodin did not abandon his belief in naturalism. In 1876, after a transformative trip to Italy, he submitted his first life-sized standing bronze statue to the Salon; inspired by Michelangelo’s The Dying Slave, it was simply titled The Age of Bronze. Although puzzled by its lack of a theme, the Salon jury accepted the sculpture, but Rodin was not yet out of the woods; the figure was considered so naturalistic that he was accused of having cast it from life. He defended himself vigorously, producing photographs and even an actual cast of the Belgian soldier who had modelled for the work, and, eventually, the charge was dropped.

Life and times of Rodin

- 1840 François Auguste René Rodin is born on November 12 to a police inspector and a former seamstress in a working-class district of Paris

- 1857–59 Fails entrance exam to the École des Beaux-Arts three times in succession

- 1864 Meets Rose Beuret

- 1865 Cast of The Man with the Broken Nose is rejected by the Salon

- 1871–76 Works as an ornamental sculptor in Brussels

- 1877 Shows The Age of Bronze at the Salon

- 1880 Receives government commission for The Gates of Hell

- 1884 Employs Camille Claudel as a studio assistant

- 1892 Relationship with Claudel ends

- 1900 Organises solo exhibition in the Place de l’Alma during the Paris Exposition Universelle

- 1913 Claudel enters a psychiatric institution

- 1917 Marries Beuret on February 14 two weeks before her death, following her himself on November 17

As it turned out, the controversy worked in his favour. The publicity made the name of the unknown 37-year-old sculptor and a government minister on the investigating committee, Edmund Turquet, was so impressed by the work that, four years later, he won Rodin the major public commission that would change his life and the course of sculptural history. ‘My head was like an egg waiting to hatch,’ Rodin remembered later. ‘Turquet broke the shell.’

The French State was planning a Museum of Decorative Arts and Rodin was asked to design its monumental bronze door, for which, inspired by Dante’s Inferno, he chose the theme of The Gates of Hell. However, as did so many of his public commissions, the project foundered: the plans were shelved, the museum was never built and Rodin’s masterwork first saw the light of day in plaster in the Pavillon de l’Alma, with several figures missing. It would not be cast in bronze until 1926, seven years after his death. His years of labour, however, were not wasted. For the rest of his life, he would use and reuse the figures he had sculpted for The Gates, turning them into independent sculptures in marble or bronze.

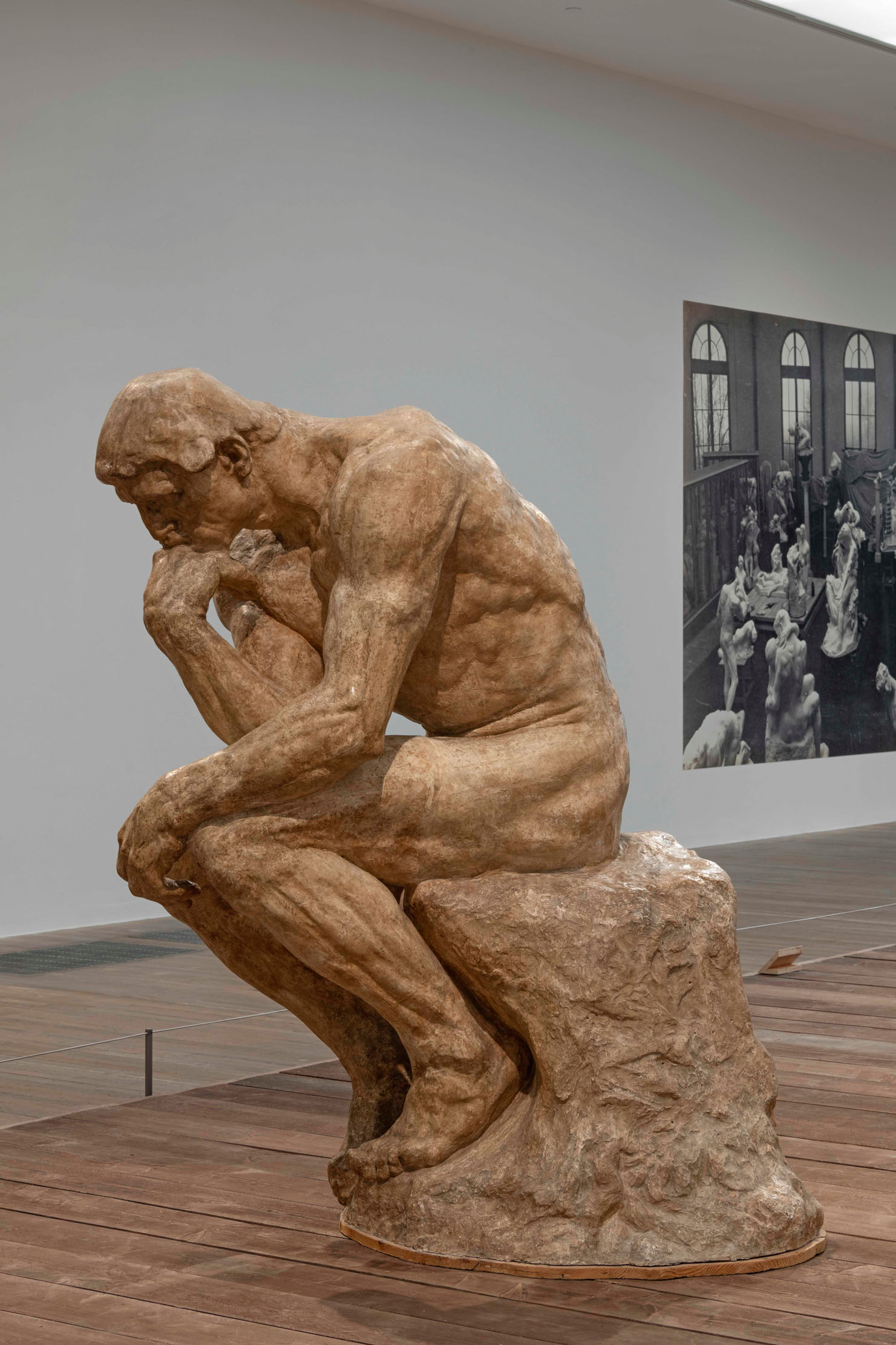

The Gates, Rodin acknowledged, were ‘the source of almost everything that met with success’. Their most famous spin-off was the sculpture of Dante’s lovers Paolo and Francesca now known as The Kiss — not actually included in their final design — but their most iconic image remains that of the powerful seated figure who presides over the whole conception, meant initially to represent Dante, but identified ever since with the sculptor himself.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

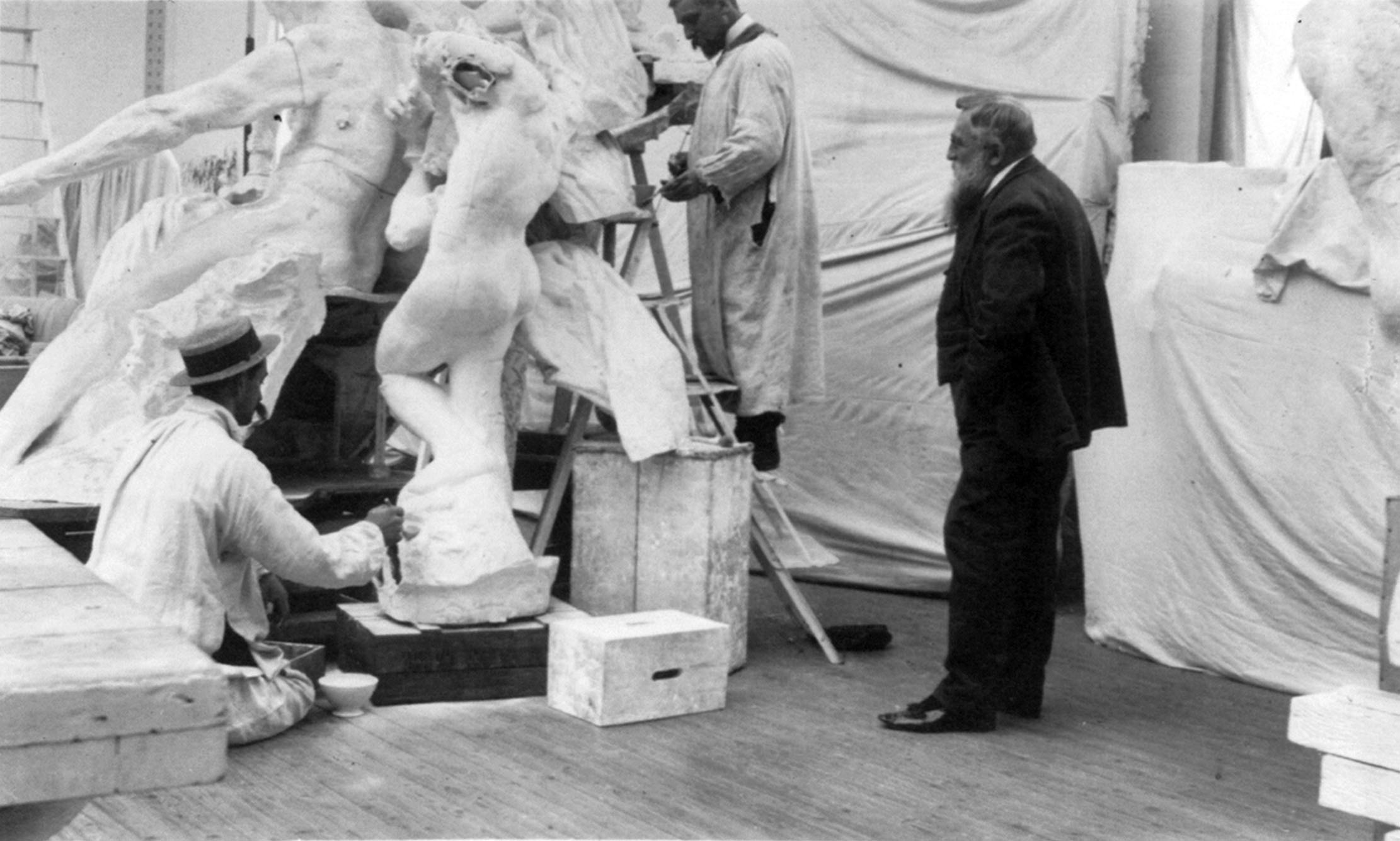

For those who only know The Thinker in marble or bronze, the monumental plaster in Tate Modern’s new exhibition, ‘The Making of Rodin’, will be an eye-opener. Unlike the smooth whiteness of marble or the dark sheen of bronze, the reflective surface of the plaster, cast directly from the sculptor’s clay model, catches light and shade exactly as he intended. Rodin was not a marble carver or a bronze caster; he delegated these tasks to specialist technicians. In his plasters, we meet Rodin in the rough. Standing in front of the plaster models in this exhibition, we can imagine him working directly from life, making the clay ‘leap under his fingers, sometimes brutally, sometimes caressingly, wringing out a leg or an arm in a single gesture,’ in the vivid description of his protégé Paul Gsell. A contemporary photograph shows the short, myopic sculptor standing so close to the model he is breathing down her neck.

The Tate’s show, organised with the Musée Rodin in Paris, re-creates the atmosphere of the Pavillon de l’Alma by focusing entirely on the sculptor’s plasters, apart from the bronze cast of The Age of Bronze in the opening room. It confirms his reputation as the father of modern sculpture by drawing attention to his innovative working methods, such as his habit of keeping drawers full of spare parts — multiple casts of miniature arms, legs, hands and feet which he jokingly called abattis, French for giblets — to assemble and reassemble in different combinations.

Other evidence of Rodin’s modernity was his enthusiastic adoption of photography; he had all his works professionally photographed from different angles and would sometimes draw on prints to make corrections.

More importantly, he understood the new medium’s publicity value. Ten years after his sculpture of the corpulent Honoré de Balzac in his dressing gown — ‘less of a statue than a kind of strange monolith,’ observed one contemporary — was rejected by the society that commissioned it, Rodin got the young American photographer Edward Steichen in 1908 to photograph the work outdoors by moonlight, casting it in a romantic light that helped to swing opinion in its favour. So delighted was he with the effect achieved that Steichen found 2,000FR under his plate at breakfast the next day. Rodin’s usual rate for photographers was 1FR an hour.

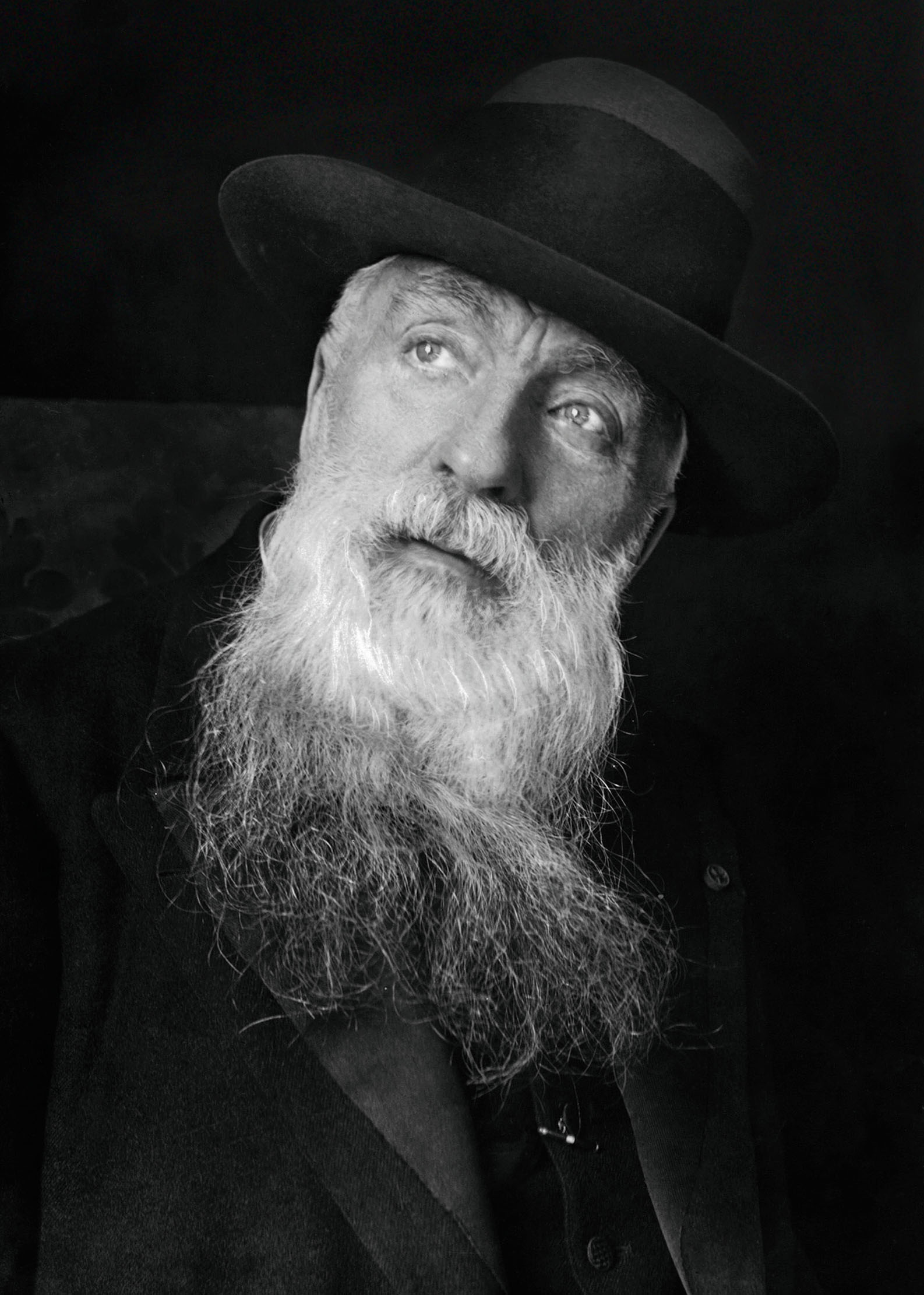

As well as thousands of photographs of his sculptures, the Musée Rodin holds some 250 publicity images of Rodin himself. The English photographers Stephen Haweis and Henry Coles described how ‘for his portrait, he would stand like a rock, anytime, anywhere, in any garb… The exposure was never too long for him’. He had a modern grasp of self-promotion: despite employing nearly 50 assistants at the height of his fame, he always had himself photographed alone in his studio, the image of the solitary genius.

After moving to the Hôtel Biron, now the Musée Rodin, in 1908, he would increasingly escape from the pressures of work and fame into one of the building’s rotundas to draw from life. ‘In this monastic retreat,’ Gsell reported in 1911, ‘he enjoys shutting himself up with the nudity of pretty young women.’

The eroticism of some of the resulting images sparked a campaign in Le Figaro to have the septuagenarian artist evicted for making ‘libidinous drawings and shameless sketches’ in a building that, only a few years earlier, had housed a convent. Perhaps aware that there is no such thing as bad publicity, Rodin carried on regardless. He was not only the father of modern sculpture; he was the first global celebrity artist.

‘The Making of Rodin’ runs until November 21 at Tate Modern, London SE1 — www.tate.org.uk

Credit: © Musée Rodin

In Focus: Rodin's quirky take on one of the treasures of the Elgin Marbles

Curious Questions: Is kissing good for you?

Annunciata Elwes asks the question on everyone's lips.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel

-

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwards

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwardsCampaigners in England often point to Scotland as an example of how brilliantly Right to Roam works, but it's not all it's cracked up to be, says Patrick Galbraith.

By Patrick Galbraith