In Focus: How British artists contributed to the uncanny, desirous world of Surrealism

Michael Murray-Fennell delves into the subconscious, the uncanny, war and desire and discovers the contribution made by British artists to the Surrealist movement.

The International Surrealist Bulletin of September 1936 announced the arrival of Surrealism in Britain. On the cover was a black-and-white photograph of Trafalgar Square with the Landseer Lions and the dome and portico of the National Gallery in the background.

Front and centre, among the pigeons, stands a woman performance artist, Sheila Legge, dressed in a satin evening dress and elbow-length gloves, but with her face entirely obscured by a mask of rose blooms.

The image combines disinhibition and desire, the uncanny and the unconscious. In the best tradition of Surrealist art, it is – even today – quite unsettling. The pamphlet with the photograph (price: one shilling) is included in a new, eye-opening survey of British Surrealism that features a combination of well-known and all-but-forgotten artists from the inter-war period and the Second World War.

Surrealism was founded in Paris with a series of manifestos (the Surrealists loved a good tract) in 1924, but it wasn’t until the early 1930s that it gained a foothold in Britain – at first with exhibitions of work by the move-ment’s rising European stars.

In 1936, one such star, Salvador Dalí, took to the stage in London dressed in a deep-sea diving suit, the perfect visual metaphor, he claimed, for his desire to dive into the depths of the human subconscious.

His lecture entreating British artists to join the Surrealist movement didn’t go quite as he envisioned, however. The diving suit was perfectly sealed and the Spaniard soon began to gesticulate that he couldn’t breathe; he collapsed and the heavy helmet had to be hastily prised off before he suffocated.

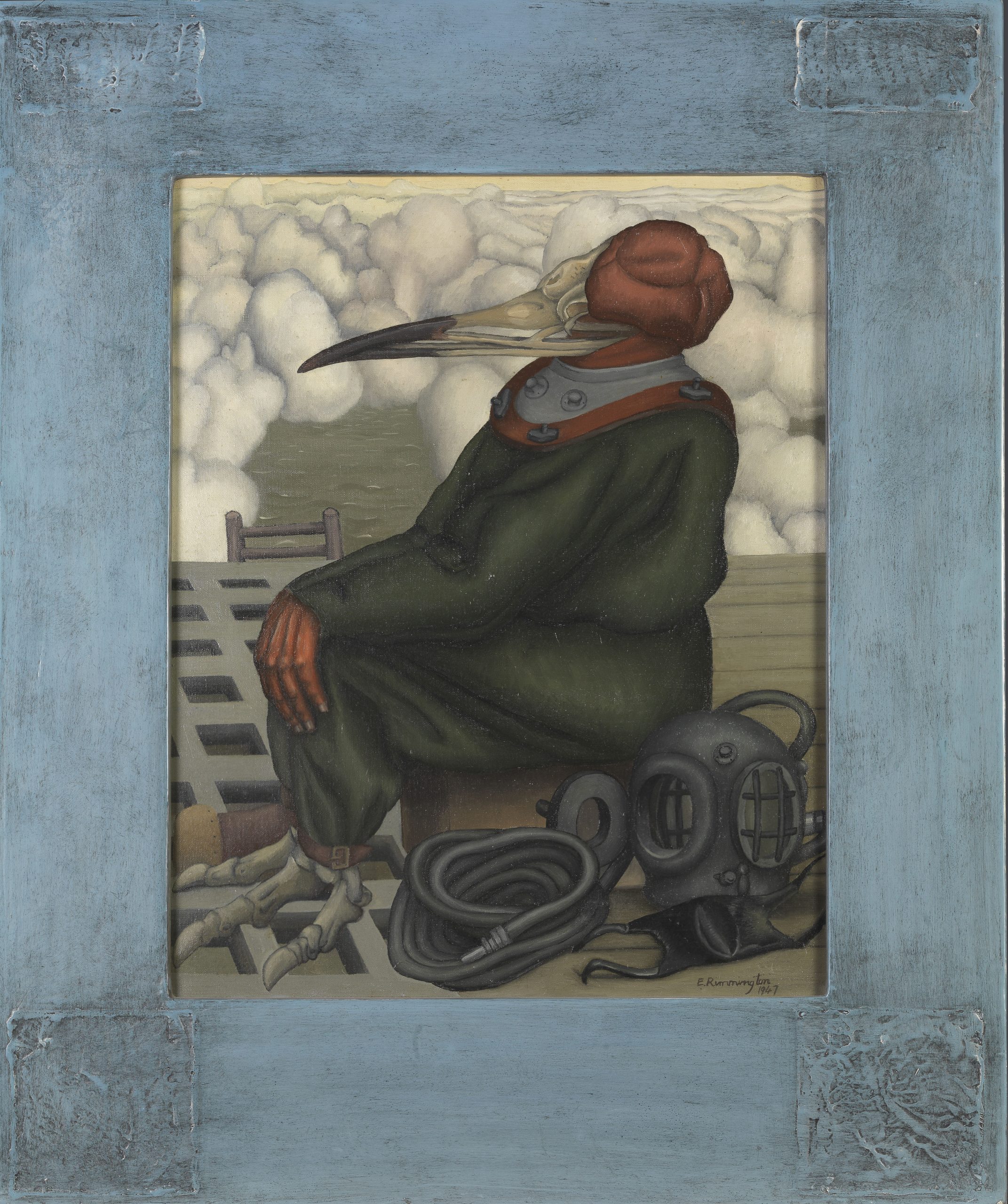

Eleven years later, and inspired by the incident, Leicester-born Edith Rimmington painted a half-human, half-bird-like figure with a diver’s apparatus by its side.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The work’s title, The Oneiroscopist, means the interpreter of dreams; Rimmington’s creature sits on a platform high up among the clouds, the top of a ladder hinting that it will soon be descending into an ocean of the subconscious.

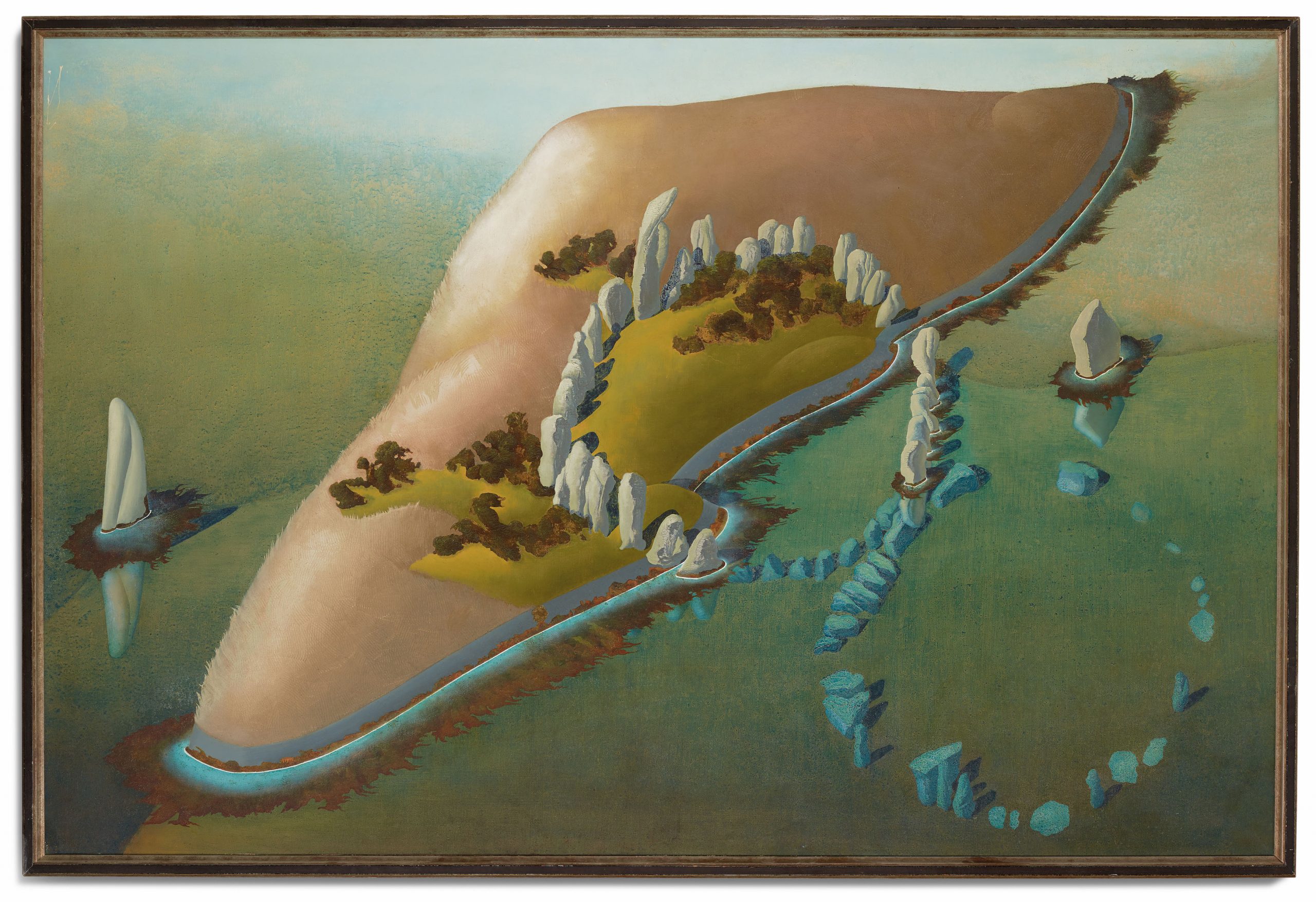

‘My life is uneventful, but sometimes I have an interesting dream,’ wrote Ithell Colquhoun, who was educated at Cheltenham Ladies College before studying art at the Slade. Fascinated by megaliths, she painted two stone circles in La Cathédrale Engloutie, one fully submerged in aquamarine, the other standing half in water and half on a small island, the shape of which suggests a female breast. Colquhoun makes an ancient landscape both sensual and dreamlike.

'It became absurd to compose Surrealist confections, when high explosives could do it so much better'

Rimmington and Colquhoun are among the less familiar names in the Dulwich exhibition. As an excellent essay by Sacha Llewellyn in the accompanying catalogue makes clear, one of the reasons that they – as well as artists Marion Adnams and Grace Pailthorpe – are largely unknown is because they were women who, as Colquhoun drily reminisced, ‘were admitted but not required’ within the Surrealist movement.

Its founder, André Breton, insisted that the Surrealist tendency ‘always has existed’ and the exhibition features a number of British ‘ancestors’ of the movement, including Henry Fuseli, Lewis Carroll and William Blake.

A print of Fuseli’s The Nightmare, showing an ogre squatting on the chest of a young woman asleep, is probably the most menacing thing in the show and undoubtedly chimes with the Surrealists’ fascination with the erotic potential of dreams.

Carroll was a firm favourite of the Surrealists, who admired his topsy-turvy Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, as well as John Tenniel’s illustrations of Alice’s exploits. The exhibition includes a note from the British painter Eileen Agar, who describes him as ‘a mysterious master of time and imagination, the Herald of Sur-Realism and freedom, a prophet of the Future and an uprooter of the Past’.

William Blake was another so-called ancestor and Paul Nash references his poem The Tyger with a collage placing a vivid engraving of an orange tiger against a black-and-white photograph of a ruin in the Forest of Dean. This juxtaposition of completely different, foreign objects was a recurring technique of the Surrealists; they quoted with relish the 19th-century French poet the Comte de Lautréamont on the beauty of ‘the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table’.

Dalí’s lobster telephone is the best known example of this splicing together of unrelated items, but the exhibition includes a British equivalent by Conroy Maddox – a typewriter, with upturned nails on each key, sitting on a plump red velvet cushion with gold tassles.

The Second World War all but closed the British chapter of Surrealism. ‘It became absurd to compose Surrealist confections,’ recalled one of their number, ‘when high explosives could do it so much better.’

Yet some responded brilliantly to the horror on the Home Front. Edward Burra’s Blue Baby, Blitz over Britain from 1941 shows a grotesque, cartoonish (think Sesame Street) bird figure looming over a ruined scene with Edvard Munch-like figures cowering and fleeing.

It is a brilliant mixture of the comic and macabre.

In Focus: The Spanish painter whose visceral depictions of martyrdom still have the power to shock

The unflinching representations of brutality in Jusepe de Ribera's images of martyrdom is the focus of a new exhibition, the

Credit: Alamy

In Focus: A grim masterpiece of the French painter who became the ultimate storyteller in paint

Laura Freeman examines the brilliance and bravado of Eugène Delacroix’s paintings – including an extraordinary recreation of one of the most

In Focus: The masterpiece painted in Cornwall by an iconic Finnish artist

Helen Schjerfbeck is a national icon in Finland but hasn't had a solo exhibition in Britain since the 19th century.

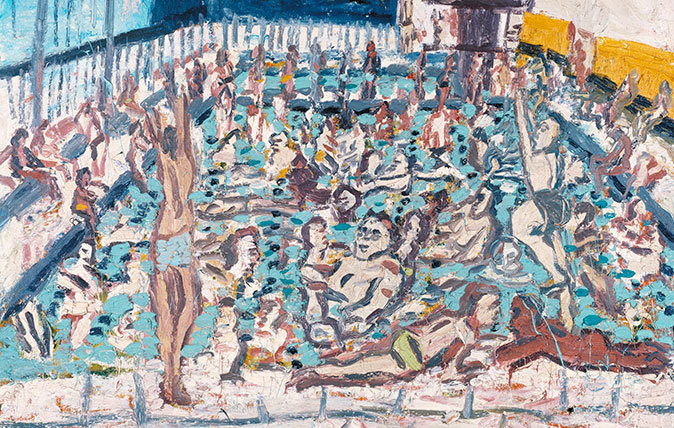

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

In Focus: The Pre-Raphaelite sisters who fought for recognition in the shadow of the Brotherhood

Caroline Bugler admires the National Portrait Gallery's new exhibition, 'The Pre-Raphaelite Sisters', which reveals the creative role of women in

In Focus: Ruskin, Turner and the ‘prophetic warning of impending environmental catastrophe’

Simon Poë is blown away by ‘Ruskin, Turner & the Storm Cloud’ at the Abbott Hall Art Gallery in Kendal,

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher

-

In Focus: How the 'Tottering Hall' cartoonist became a sculptor

In Focus: How the 'Tottering Hall' cartoonist became a sculptorBest known as the creative force behind Dicky and Daffy, it was her son’s death that prompted Annie Tempest to learn ‘the grammar of the sculptor’s language’, discovers Ian Collins.

By Country Life

-

In Focus: How Italy inspired JMW Turner

In Focus: How Italy inspired JMW TurnerMary Miers considers how the country that fascinated Turner from youth shaped his artistic vision.

By Mary Miers

-

In Focus: Why the eerie thrives in art and culture

In Focus: Why the eerie thrives in art and cultureThe tradition of ‘eerie’ literature and art, invoking fear, unease and dread, has flourished in the shadows of British landscape culture for centuries, says Robert Macfarlane.

By Country Life

-

In Focus: John Hassall's iconic travel posters

In Focus: John Hassall's iconic travel postersThe works of British poster king John Hassall remain a breath of fresh seaside air, says Lucinda Gosling.

By Country Life

-

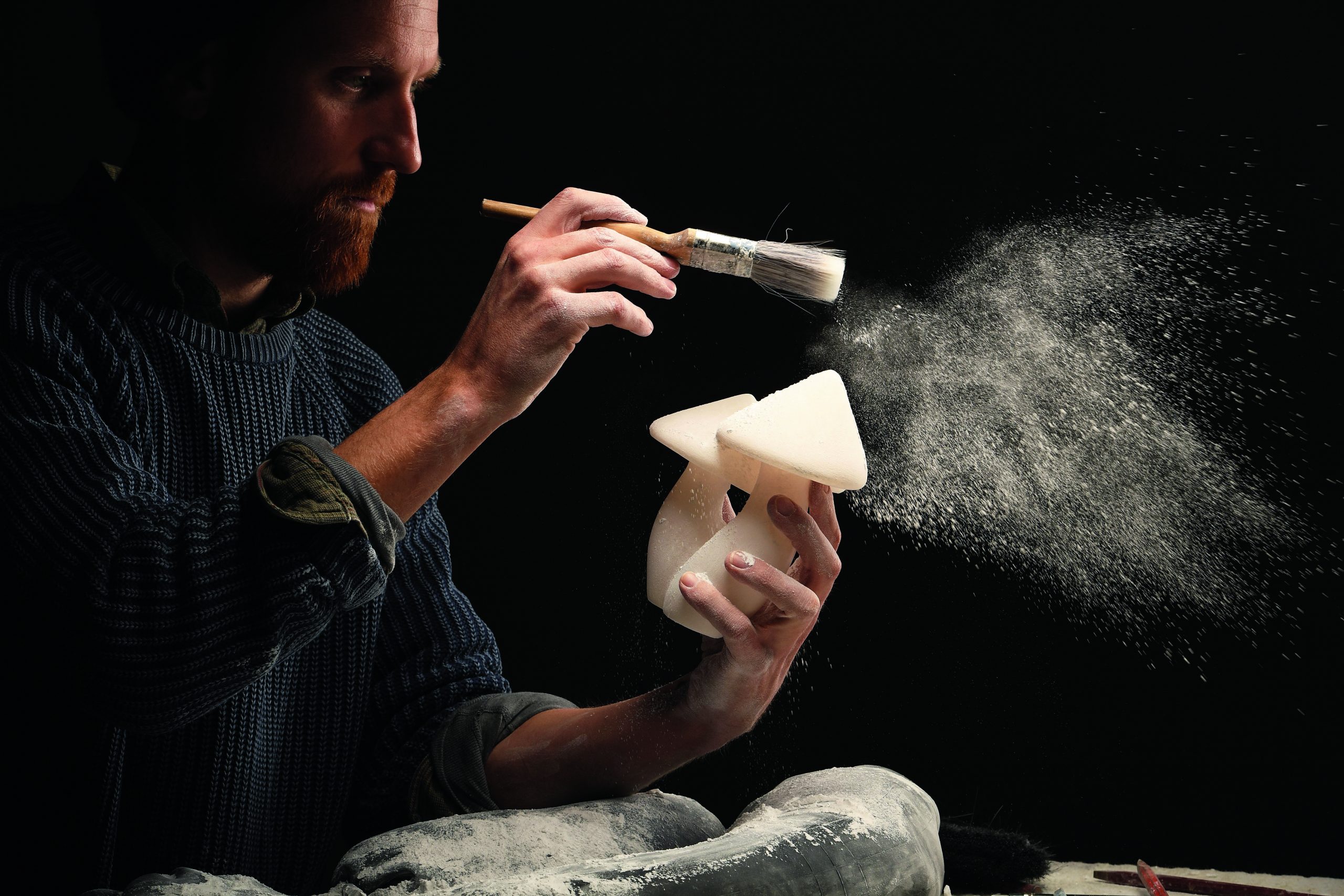

In Focus: the fungi sculptures that bend stone into soft, flowing forms

In Focus: the fungi sculptures that bend stone into soft, flowing formsThey may look as delicate and organic as the real thing, but Ben Russell’s sculptures of fungi, cacti and roots will outlast us all, believes Natasha Goodfellow.

By Country Life

-

In Focus: How 21st century artists are reviving the art of the fresco

In Focus: How 21st century artists are reviving the art of the frescoOnce practised by Michelangelo, Raphael and da Vinci, the art of fresco creation has changed little in 1,000 years. Marsha O’Mahony meets the artists following in their footsteps.

By Country Life

-

Why a good frame can be a work of art in its own right

Why a good frame can be a work of art in its own rightCatriona Gray retraces the history of frames, admires the craftsmanship required to make them and discovers what's the best way to preserve them.

By Country Life

-

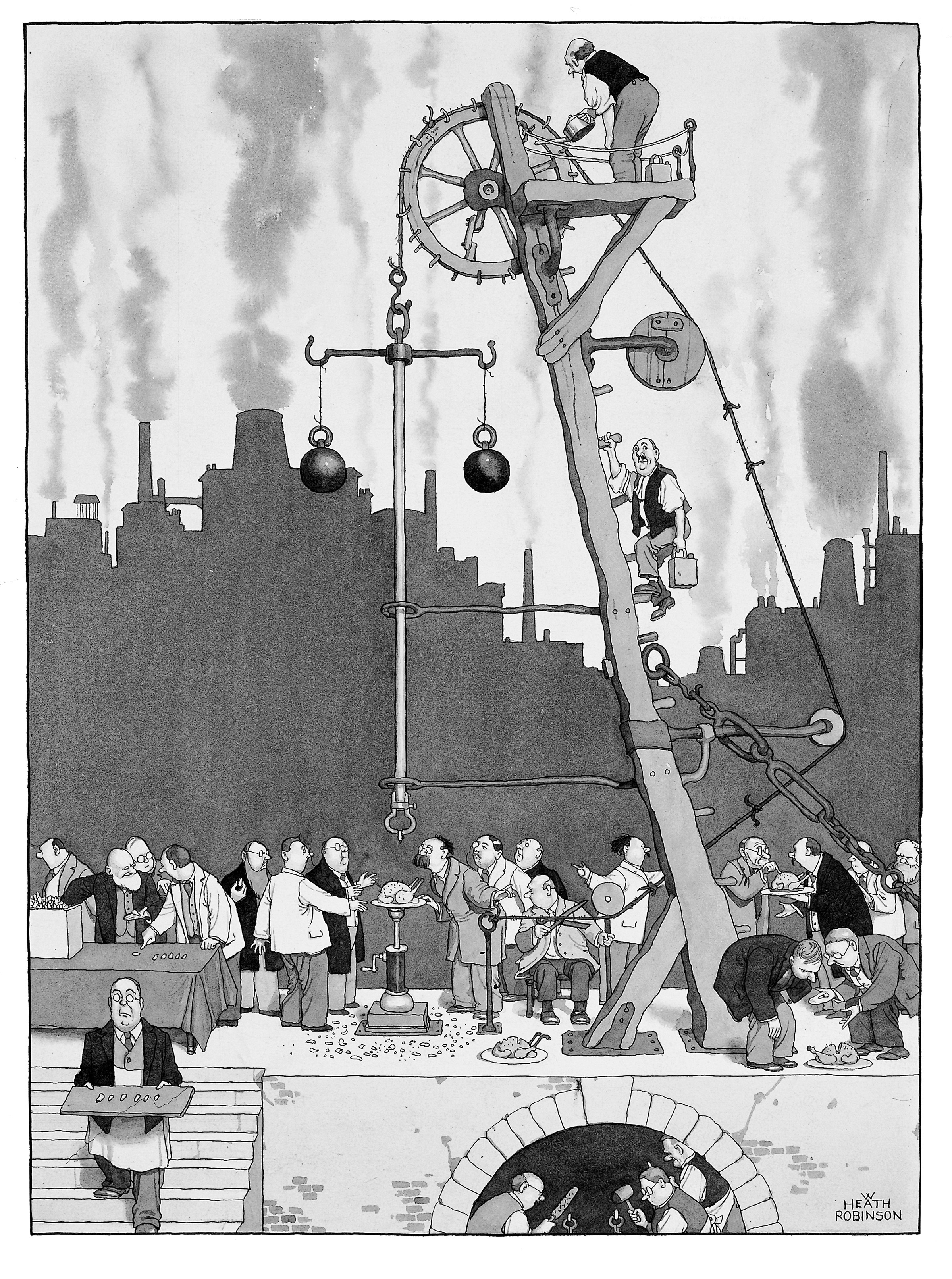

In Focus: The Heath Robinson Museum at Pinner, home to decades of gently satirised modern life

In Focus: The Heath Robinson Museum at Pinner, home to decades of gently satirised modern lifeHuon Mallalieu tells the story of the small museum in Middlesex, where you'll find the last records of the county before it became overrun by suburbia.

By Huon Mallalieu