In Focus: Eric Ravilious, the war artist with a fascination with the quotidian whose work was 'sharp in detail, clean in colour' and 'quietly revolutionary'

Known as ‘the boy’ and only 39 when he died on active service in the Second World War, Eric Ravilious had already accomplished so much, thanks to his fastidious eye for mundane detail, says Peyton Skipwith.

On September 5, 1942, Tirzah Ravilious received a letter from the Admiralty informing her that her husband ‘Temporary Captain Eric Ravilious, Royal Marines, has been reported missing since Wednesday last, September 2, 1942, when the aircraft in which he was a passenger failed to return from a patrol’.

Seven months later (March 17, 1943), she received another letter, this time from his fellow artist Edward Bawden: ‘No one I know or have known seems to possess what he had, an almost flawless taste… But my dear Tirzah it is so much more than all that — I simply can’t tell you, or anyone else, or even myself what it is, or how much it is I miss by losing Eric…’

Bawden, who had only just got back to England from seven months of internment in a Vichy prison camp in Morocco, had, together with Douglas Percy Bliss, been Eric’s closest friend from student days.

His use of the adverb ‘almost’ pinpoints, without hyperbole, the precise quality that sets Ravilious—‘the boy’, as he was known—apart and makes his work unique. Others had commented on it, too, during his student days at the Royal College of Art, where Bliss described him as ‘fastidious and assimilative, culling his fruits from any bough… [sifting] with the skill of an anthologist the rare things that could help him in his work… [going] his own way, rather like a sleep-walker, but with a sure step and an unswerving instinct for style’.

Born in Acton, London, Ravilious was brought up in sight of the South Downs, his family having moved to Eastbourne, East Sussex, where he attended art school before winning a scholarship to the Royal College of Art (RCA). It was an exciting time, as the college was being transformed under the direction of its new principal, Sir William Rothenstein. A painter, printmaker, draughtsman and writer on art, Sir William not only split it into separate schools—of painting, sculpture, design and printing—but also introduced part-time teachers, including Paul Nash, who was to have a profound effect on Ravilious, enthusing him with the work of Claud Lovat Fraser (Country Life, May 19, 2021) and his designs for pattern papers, among other things.

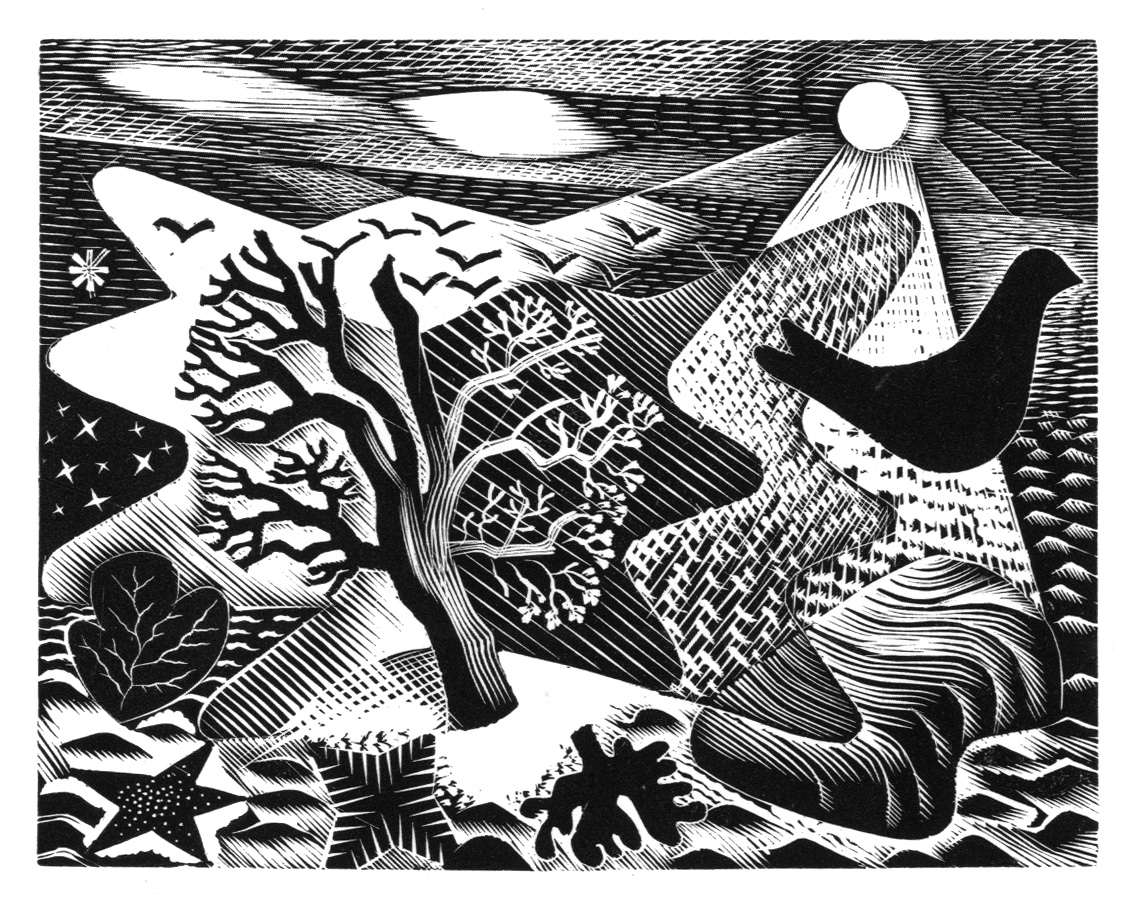

At college, Ravilious discovered the joys of wood-engraving and his first ambitious print in this medium was reproduced in the student magazine Gallimaufry. On returning from a travelling scholarship to Italy, he was introduced by Sir William to Oliver Simon, a cousin and partner in the Curwen Press, which became a steady source of engraving commissions throughout the next decade.

In the wake of the triumphant reception of Rex Whistler’s mural In Pursuit of Rare Meats at Tate Gallery, commissioned by Sir Joseph Duveen, Sir William challenged Sir Joseph to sponsor a similar scheme for RCA students, Whistler being Slade-trained. In the event, Ravilious, Bawden and Charles Mahoney were commissioned to provide murals for Morley College in South London. Ravilious and Bawden, working in tandem, were allotted the refreshment room and produced a delightful fantasy largely based on Shakespearean plays, albeit with the inclusion of various airborne gods and goddesses, as well as the interior of a contemporary lodging house in which Tirzah made her debut. The Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, temporarily out of office, unveiling the mural in February 1930, declared it had been ‘conceived in a spirit of happiness and joy’. Sadly, it lasted barely 10 years before being destroyed in the Blitz.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

During all the years I knew Bawden, he seldom spoke of Ravilious, although the latter’s Morley study, Harlequin, hung in his house as an ever-present reminder of happier times. Today, the only surviving records consist of studies, photographs and the portraits the two men painted of each other at the time.

In a rare excursion into tempera, Ravilious painted Bawden at work in a cluttered room with rolls of paper—studies for the 1930 mural—rising like organ pipes in the corner, with Bawden depicting his friend equally at work, albeit partially obscured by a large vase of flowers. They were paid £1 for each day’s work with materials provided: it took longer than anticipated. Once done, basking in temporary glory, the two friends bicycled into the Essex countryside searching for a site for a summer campaign of painting. They took lodgings at Brick House, Great Bardfield, and, for the next few years, the Essex countryside, together with the South Downs, provided Ravilious with material for his landscapes.

The work of the two men was quietly revolutionary; they rejected the fluidity of watercolour favoured by Sargent and Alfred Rich in favour of a more austere approach inspired in part by the work of Francis Towne and John Sell Cotman. For Ravilious, the discipline of wood-engraving—its clarity cutting straight to the core—undoubtedly played a part in refining his vision. Telegraph poles, waterwheels, barbed wire—details that others rejected as unsightly—became for him vital points in the living landscape. Similarly, garden tools, household utensils, the pattern of a lodging-house wallpaper or the moquette of a third-class railway carriage were all capable of supplying material for pencil, brush or graver. In the exhibition ‘Extraordinary Everyday’, currently on show in Winchester, Hampshire, curator James Russell explores Ravilious’s fascination with the quotidian.

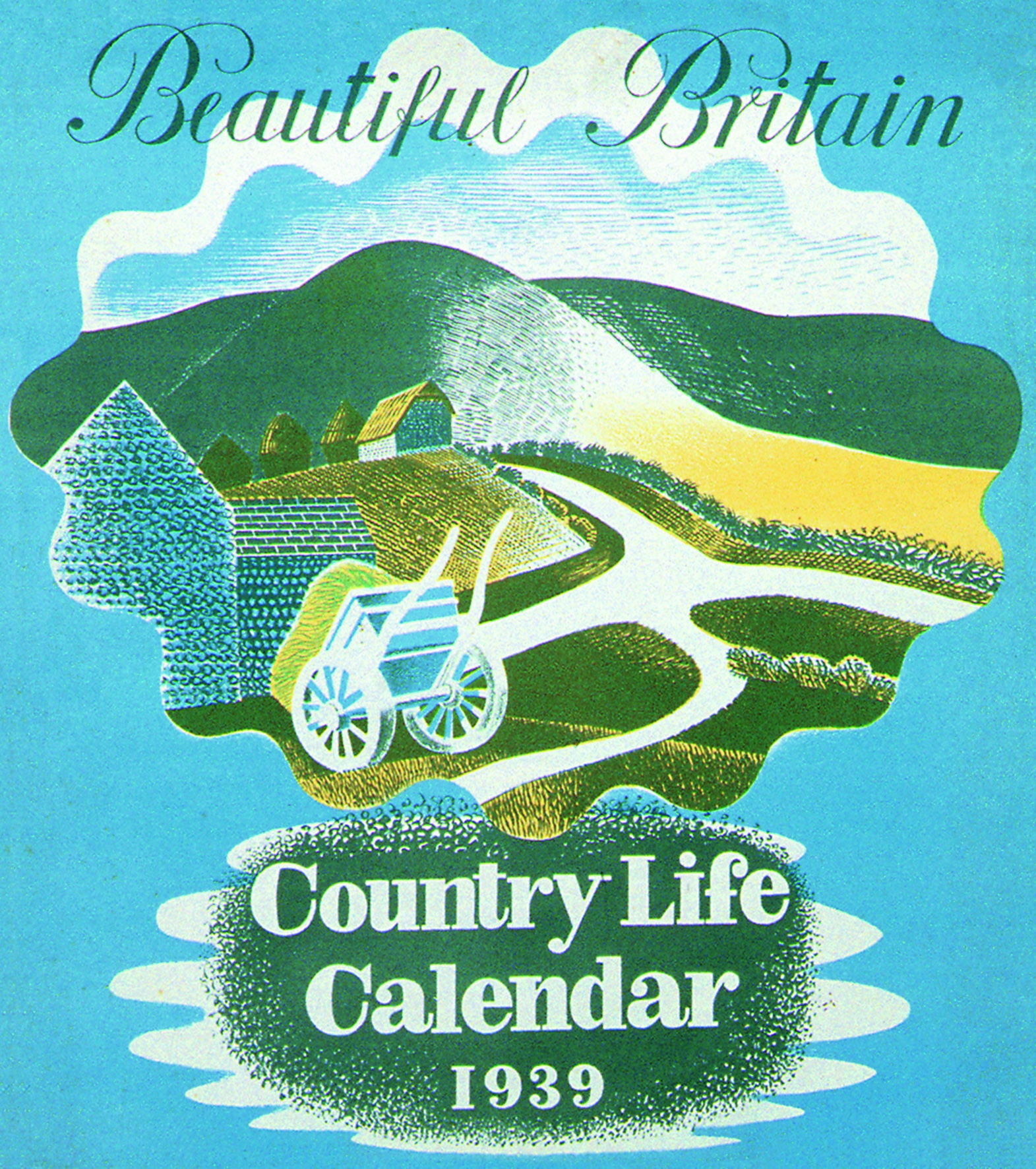

The artist was fortunate in catching the tail end of luxury book production before the effects of the Wall Street crash took their toll, producing engravings for the Monotype Corporations 1929 Almanack and the Golden Cockerel’s Twelfth Night. Much of his later engraved work was commissioned through the Curwen Press by such bodies as Southern Railways, London Transport and Country Life, as well as Whitaker’s—he produced the iconic cover image of top-hatted cricketers for Wisden’s Almanack.

One final glory was Ravilious and Nonesuch Press’s two-volume edition of Gilbert White’s The Natural History of Selborne, published in 1938, the same year that Country Life published ‘High Street’, his earliest essay in auto-lithography. Among the various shop fronts depicted is a newsagent’s window filled with fireworks in anticipation of November 5.

The artist’s delight in pyrotechnics had already been exuberantly revealed in his ill-fated mural for the Midland Railway Hotel at Morecambe, Lancashire, as well as in his design for Wedgwood’s Edward VIII Coronation Mug and his cover design for the Guide to the British Pavilion at the Paris World Fair.

Late in 1939, Ravilious was appointed an Official War Artist attached to the Admiralty and posted to Chatham. The following spring, he was assigned to HMS Highlander for a voyage to Norway and the Arctic Circle. His reaction was ecstatic: ‘I’ve done drawings of the Midnight Sun and the hills of the Chankly Bore… it is about the first time since the war that I have felt peace of mind or desire to work.’ The result was some of his finest watercolours, HMS Glorious in the Arctic (1940) and HMS Ark Royal in Action among them.

On his return, he spent time at Portsmouth drawing submarine interiors, but the lure of the Arctic remained and, when the chance of a posting to Iceland occurred, he jumped at it. He was there for only six days before that fatal flight, the only tangible vestige of which was the wheel of a Hudson aircraft washed ashore six days later.

Hampshire Cultural Trust’s exhibition ‘Extraordinary Everyday: The Art and Design of Eric Ravilious’ is at The Arc in Winchester, until May 15 — see www.arcwinchester.org.uk

The Life and Times of Eric Ravilious

July 22, 1903 — Born in Acton, West London

1919 — Attends the Eastbourne School of Art, East Sussex

1922 — Awarded a scholarship to the Royal College of Art

1925 — Elected to the Society of Wood Engravers

1927 — Illustrates Nicholas Breton’s The Twelve Moneths; exhibits with Edward Bawden and Douglas Percy Bliss at St George’s Gallery, London

1928 — Commissioned with Bawden to paint a mural for Morley College

February 1930 — Stanley Baldwin unveils Morley College murals; Ravilious marries Tirzah Garwood on July 5

1932 — Designs Twelfth Night for Golden Cockerel Press; moves to Brick House, Great Bardfield, Essex

1933 — Makes engravings for The Famous Tragedy of the Rich Jew of Malta, murals for Midland Railway Hotel in Morecambe, Lancashire, and, in November, stages a one-man exhibition at Zwemmer’s Gallery, London

1934 — Rents Bank House, Castle Hedingham, Essex

1936 — Designs Edward VIII Coronation Mug for Wedgwood

1937 — Engravings for The Country Life Cookery Book; designs exhibit and catalogue for British Pavilion, Paris International Exhibition

1938 — Illustrates Nonesuch Press edition of The Natural History of Selborne

December 1939 — Appointed Official War Artist attached to the Admiralty

1940 — Working at Chatham, Sheerness, Whitstable and Grimsby, May–June, with HMS Highlander to Norway; drawings for submarine interiors at Portsmouth

1941 — Submarine lithographs exhibited at Leicester Galleries, London

1942 — Spring, with the RAF in Yorkshire, Essex and Hertfordshire; August 28 posted to RAF Kaldadarnes, Iceland

September 2, — 1942 — Reported missing

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.