In Focus — Beatrix Potter: Remarkable, doughty, gifted, intimidating, and a child who just never grew up

Beatix Potter's unforgettable children's stories have left an indelible mark on the cultural life of Britain. Here, her biographer Matthew Dennison looks at her life, work and legacy, and examines the V&A's new exhibition about her life: 'Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature’.

Beatrix Potter loved, respected and, on occasion, in her later life as a Lakeland farmer, feared Nature: boundless curiosity fired her engagement with the world around her.

In her own assessment one of the ‘children-who-have-never-grown-up’, she retained lifelong the sense of wonder she had conceived as a child. She was fascinated by butterfly wings and ‘white scented funguses’; her pet lizard Judy; the ‘two great cedars’, their branches like ‘outstretched arms’, their green bark splashed with red, that punctuated the velvet lawns of her grandfather’s house in Hertfordshire; and her succession of tame rabbits, trained to perform simple tricks.

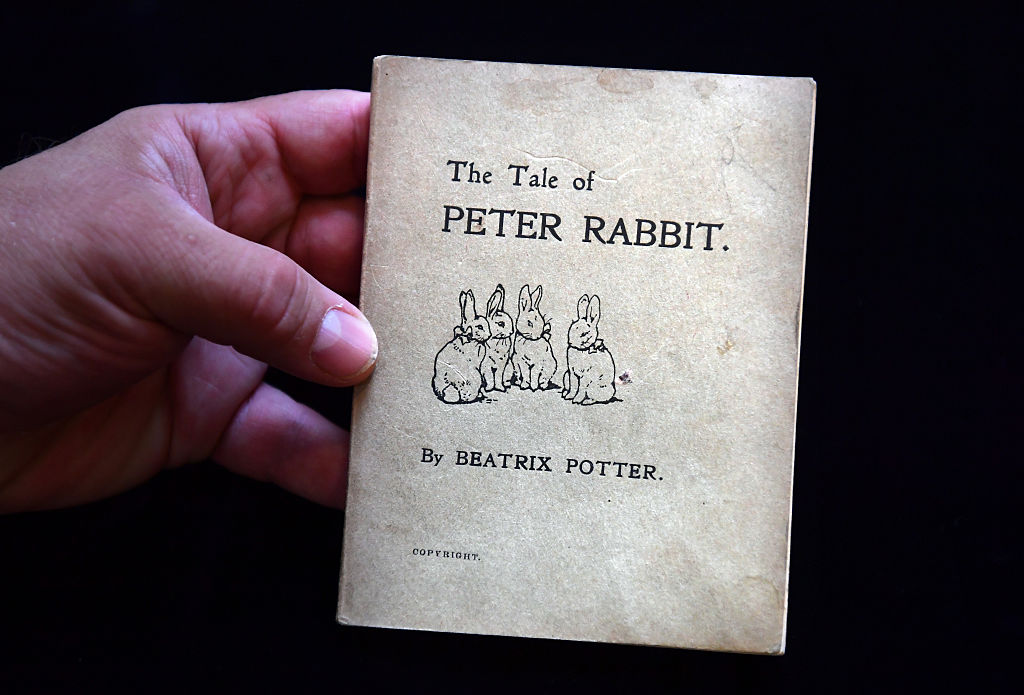

These culminated in Peter, ‘bought at a very tender age, in the Uxbridge Road, Shepherd’s Bush, for the exorbitant sum of 4/6’ and afterwards immortalised in The Tale of Peter Rabbit, which has since sold more than 40 million copies. ‘The spirit of enquiry leads up a lane which hath no ending,’ Potter wrote in 1892, at the age of 26. In her own case, it was quite true.

The wholeheartedness of her curiosity played a key part in the success of what, with mixed emotions, she called her ‘little books’ and emerges powerfully from a new exhibition at the V&A Museum, ‘Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature’.

Among the works on display are images of a terrapin, pomegranates, water lilies, a hedgehog, sea holly, a bat’s skeleton and the fungi that fascinated her in her twenties, ultimately leading to the research paper she submitted to the Linnean Society in 1897, On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricineae, as well as sketches of Judy the lizard and Peter the rabbit. ‘I like to do my work carefully,’ Potter explained to a young reader in 1928. Here is abundant evidence of that more-than-workmanlike carefulness.

The life and times of Beatrix Potter

- July 28,1866: Helen Beatrix Potter is born at 2, Bolton Gardens, London SW5.

- 1872: Birth of her only sibling, Bertram.

- 1875: At nine, she fills a sketchbook with butterflies, caterpillars and birds .

- 1881 At 15, she begins a secret journal, in a code of her own devising.

- 1882: The Potter family takes its first Lake District holiday.

- 1883–85: Annie Carter (later Moore) becomes Potter’s governess. In time, three of Potter’s tales begin as ‘story letters’ to her former governess’s children.

- 1885: Potter is given her first pet rabbit, Benjamin.

- 1887: She contracts rheumatic fever.

- 1890: She sells her first drawings, which are used as images on greetings cards.

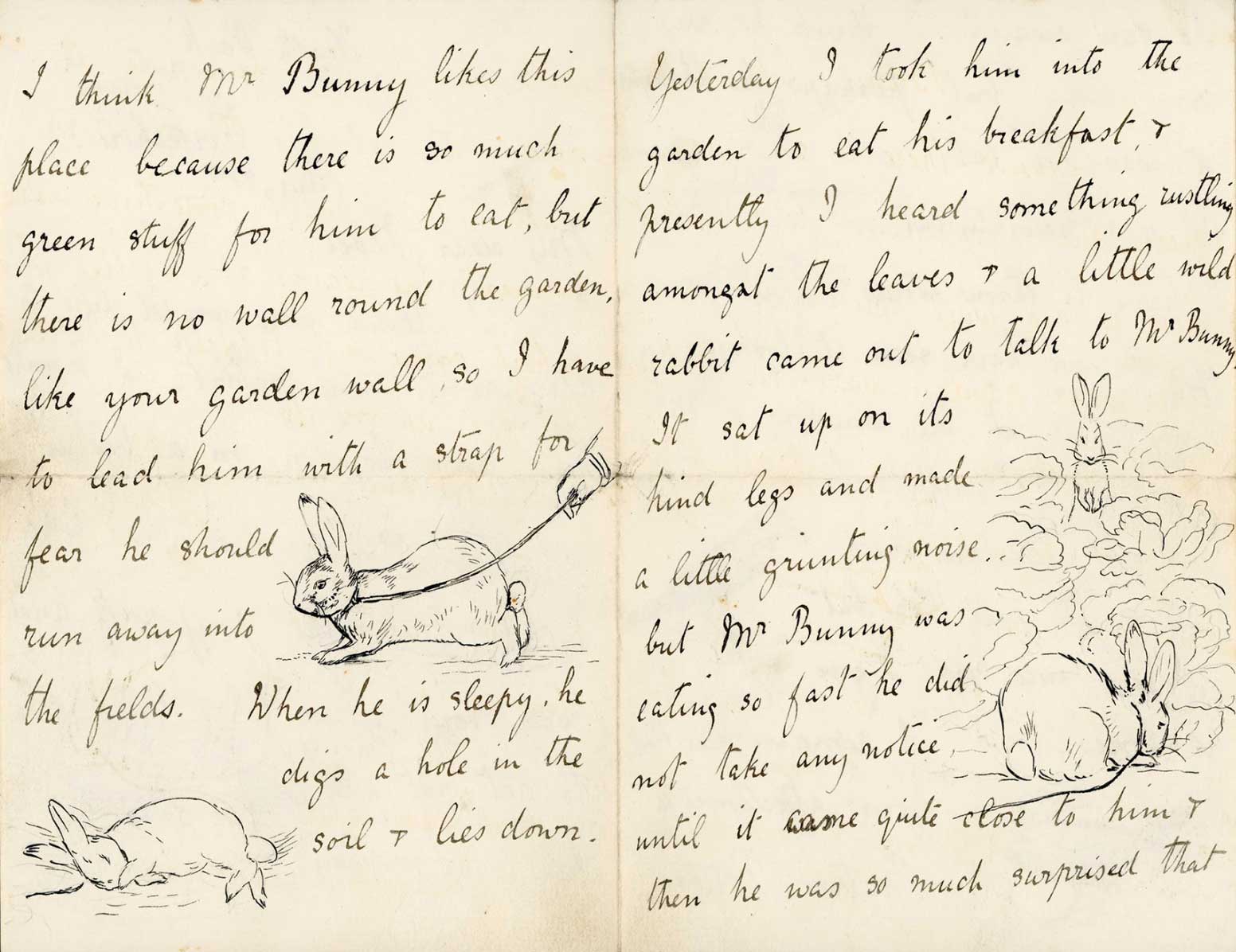

- September, 1893: Potter sends Noel and Eric Moore letters telling the stories that become The Tale of Peter Rabbit and The Tale of Jeremy Fisher.

- 1895: She sells a series of drawings, A frog he would a-wooing go, to publisher Ernest Nister; these are printed the following year.

- 1896: The Potters holiday in Near Sawrey, where the author will later settle.

- 1901: Potter sends Norah Moore a letter with the story that becomes The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin.

- December, 1901: She privately publishes The Tale of Peter Rabbit .

- October, 1902: The Tale of Peter Rabbit is published in an edition of 8,000 copies by Frederick Warne; a further 20,000 copies are printed before the end of the year. The following year, Warne releases The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin and remains Potter’s publisher until her death.

- 1905: Potter accepts Norman Warne’s proposal in July; he dies the following month. Grief-stricken, she buys a Lake District farm, Hill Top in Near Sawrey, but continues to live mostly in London with her parents.

- 1909: Potter buys her second Lake District farm, Castle Farm.

- 1913: At the age of 47, Potter marries Cumbrian solicitor William Heelis and settles in Castle Cottage, close to Hill Top.

- 1921: First foreign language (French) editions of Potter’s ‘little books’.

- 1927: She joins a campaign to preserve Windermere from developers.

- 1943: Potter is elected president of the Herdwick Sheep Breeders’ Association.

- December 22, 1943: Potter dies of bronchitis, complicated by heart problems.

As with many children whose formative years are spent in an unsympathetic or excessively uneventful environment, Potter developed a rich imaginative life, frequently more real to her than the stolid respectability of her parents’ existence at 2, Bolton Gardens, then a new development in South Kensington. In mid-Victorian London, Rupert and Helen Potter were rich outsiders.

Both were the children of dynamic, self-made men: Rupert’s father had established a calico-printing works outside Manchester; Helen’s family were cotton merchants with their own textile mills and shipping fleet. Two years before her marriage, Helen received from her father the considerable sum of £50,000. Both families were Unitarians.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The combination of Northern manufacturing and religious non-conformity barred the Potters from smart society: they evidently felt their exclusion keenly. A querulous Rupert cultivated gentlemanly aimlessness and his dour wife frittered infinite leisure in an unvarying social round of a sort that Potter parodied in her descriptions of Tabitha Twitchit’s tea parties. Rupert took up photography, Helen enjoyed the company of her canaries.

Beatrix spent a hermetic childhood in her third-floor nursery; the view from its tall windows included the roofline of the nearby Natural History Museum. A Scottish nurse, who introduced her young charge to Calvinism and frightful tales of witches and hobgoblins, gave way to a regime of governesses and, later, art tutors. She grew up believing in fairies and passionately fond of fairy tales, nursery rhymes and Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake.

Fairy tales would shape her own storytelling; later, she published two collections of nursery rhymes. Drawing and watercolour painting became the very substance of her life, until worsening eyesight and her mid-life absorption in farming altered her priorities.

In the two years I devoted to my 2016 biography of Potter, Over the Hills and Far Away, my admiration for this remarkable, doughty, gifted and rather intimidating woman never faltered. She transcended the lugubriousness of her upbringing to emerge as a writer and artist of wonderful originality who, for the first time in British publishing, created books for children in which stories and illustrations were completely and thrillingly integrated.

Her fictional world delighted, excited and inspired the children of her contemporaries and has gone on to shape the lives of generations of children across the globe: what Potter called the circle of ‘little friends of Mr McGregor & Peter & Benjamin’ is continually replenished.

A survey undertaken several years ago concluded that, somewhere in the world, one of Potter’s books is purchased every 15 seconds. This is exactly as she would have wished it. She battled hard with her publishers to ensure her books were published in a format sufficiently inexpensive to be affordable to children.

Her satisfaction was considerable when, at the end of her life, she could claim of Peter Rabbit that ‘his moderate price has at least enabled him to reach many hundreds of thousands of children, and has given them pleasure without ugliness’.

Potter’s extraordinary success was not accidental. Often dispirited as a teenager and a young woman — whose life was characterised by isolation and yawning chasms of free time — she matured into a figure of determination, resourcefulness and persistence. Unlike her parents, she had inherited the gusto and entrepreneurialism of her north-country forebears. Rupert and Helen encouraged her interest in art as long as it remained appropriately ‘ladylike’ — intended only for viewing within the family circle — but they disdained her attempts to become a published author. After a lengthy period of domestic attrition, their daughter defied them.

The story of how Potter became the artist-author of her 23 ‘little books’ is well known: a trio of these stories emerged first in letters she wrote to the children of her former governess, Annie Moore. Moore understood her charge’s plight, still confined to the nursery at Bolton Gardens in her mid thirties, and encouraged her to publish the stories.

Initially, publishers demurred and Potter self-published Peter Rabbit.

The following year, Frederick Warne brought out the book commercially. Its success was immediate and the company subsequently published all Potter’s books.

The author wrote several with the express intention of saving Warne’s firm from bankruptcy, her loyalty rooted in love. In 1905, she had become engaged to Norman Warne, only to have her prospects destroyed when, a month later, he died of leukaemia. In the eight intervening years before she married William Heelis, she wrote many of her best-loved stories in an extended burst of creativity.

As Mrs Heelis, away from her parents at last, Potter’s life was rooted in the Lake District. She embraced the challenges of hill farming, able to supplement her endeavours with her literary earnings, and made additional purchases of farmland, her focus the protection of an ancient landscape, the despoliation of which she dreaded. She almost gave up writing.

Her ‘declining years’, she claimed, were devoted to ‘old oak — and drains — and old roofs — and damp walls — oh, the repairs!’ At her death in December 1943, aged 77, she owned 14 farms and 4,000 acres, all of which she bequeathed to the National Trust.

‘Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature’ is at the V&A Museum, London SW7, until January 8, 2023. Matthew Dennison is the author of ‘Over the Hills and Far Away: The Life of Beatrix Potter’ (Head of Zeus, £18.99)

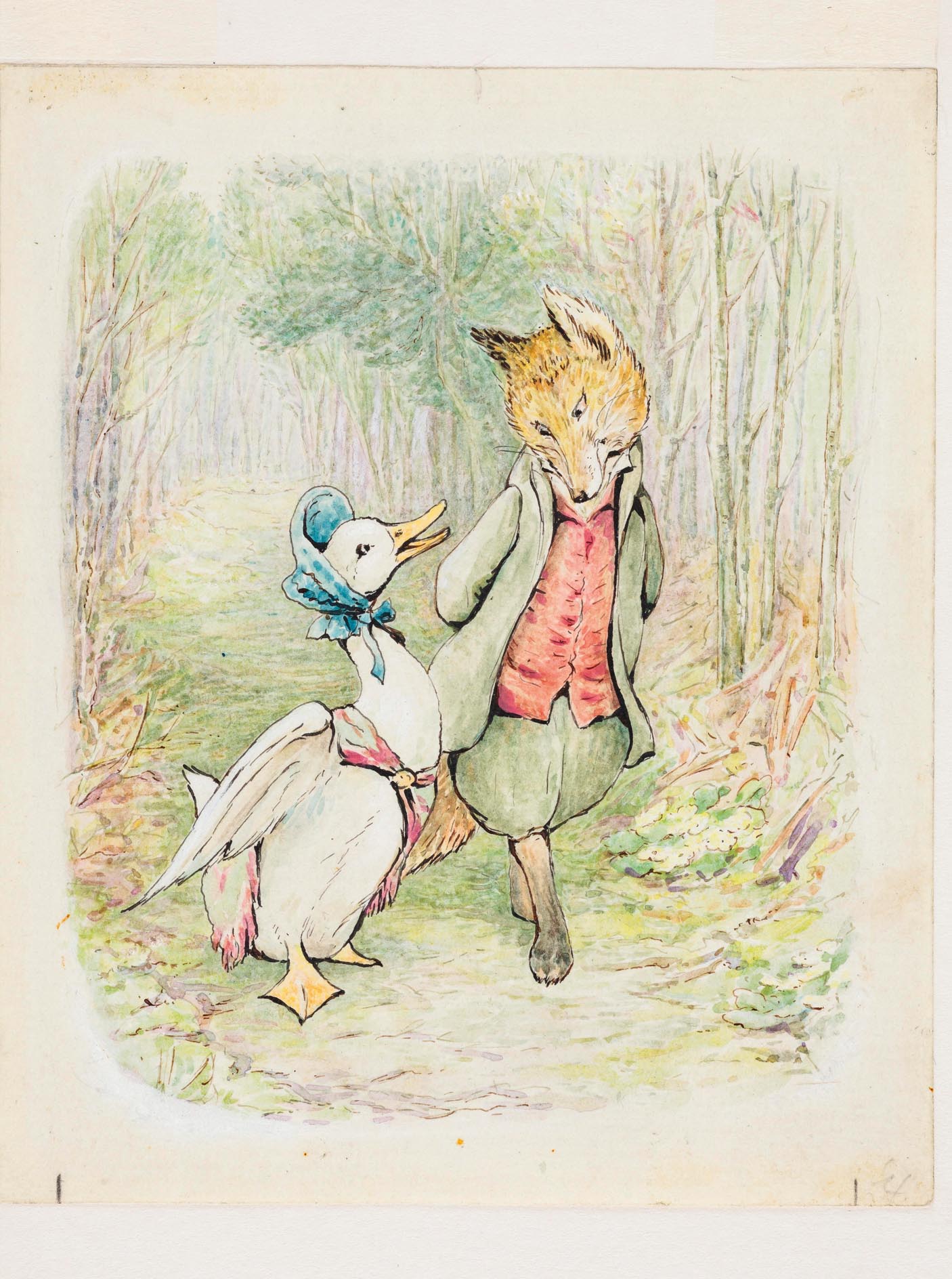

In Focus: Jemima Blackburn, the extraordinary artist of nature who became the real-life Jemima Puddle-Duck

Once regarded as a rival to Bewick and Audubon, but now largely forgotten, ornithological artist Jemima Blackburn (1823–1909) was a

Credit: John Millar

'I just know what I want to burn my energy on': The remarkable career of Patricia Routledge

The redoubtable actress Patricia Routledge talks to Country Life about being a presenter, unacceptable mannerisms and turning down Alan Bennett.