In Focus: Alfred Wallis, the painter whose art is high seas meets Kindergarten-style folk art

Self-taught mariner Alfred Wallis’s sea paintings enjoyed popularity with Modernists, but did their efforts drown his own voice? As an exhibition opens at Kettle's Yard in Cambridge, Ruth Guilding takes a closer look.

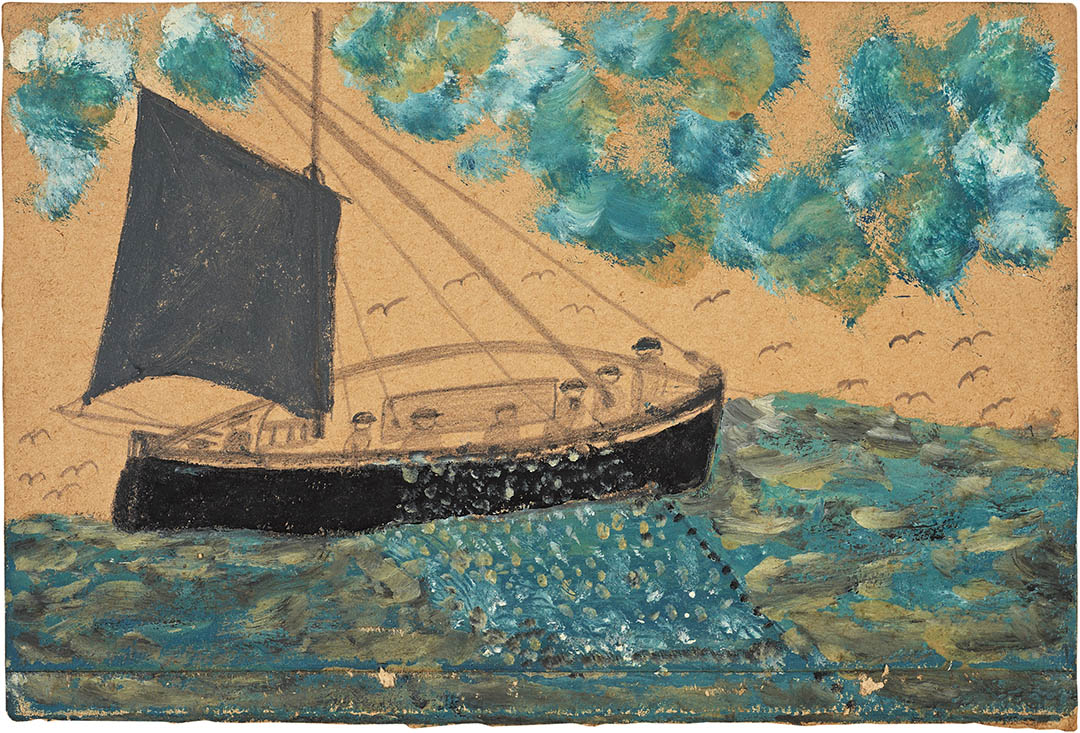

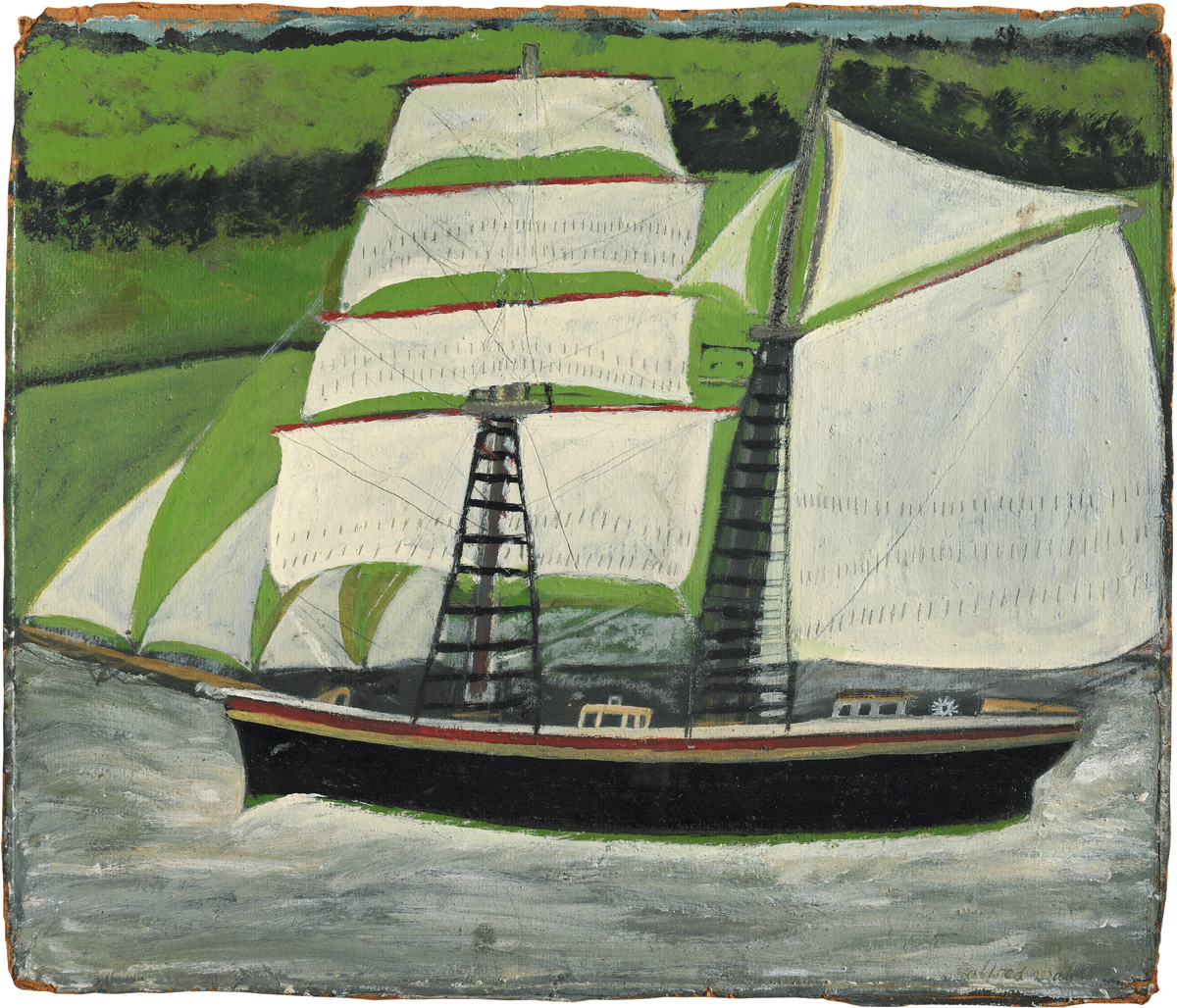

Alfred Wallis’s popular maritime paintings have been reproduced many thousands of times, on greetings cards, mugs and mouse mats. His vigorously simplified ships and high, plashy seas combine the serendipity of kindergarten painting with Folk Art's nostalgia-factor.

A mariner who went to sea at the age of nine, serving in the merchant navy and on deep-sea fishing boats before trading as a marine scrap dealer, Wallis was a childless widower in his seventies when he was first ‘discovered’ by Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood in 1928. When they spotted nailed-up paintings through his open cottage door, he told them that he had turned to painting several years earlier, ‘for company’ in his solitary state.

Their chance encounter developed into an unequal friendship, for these cosmopolitan Modernists came with their own agenda. Between them, by the time of his death, an influential cabal that included Nicholson, Wood, Adrian Stokes, Jim Ede and Herbert Read had bought up almost all of Wallis’s work.

Ede had amassed more than 120 paintings, although he had never met Wallis. This elite group became his cultural guardians, collecting and interpreting, sending regular payments for new consignments of paintings, transmuting the raw materials of his motifs, skylines and flat picture planes into their own visualisations.

Winifred Nicholson included the Wallis hanging near her chimney-piece in an interior scene, Stokes provided the sketch books that Wallis filled during his final decline in the Madron workhouse and Bernard Leach made the tiles that carapace his pauper’s grave. After the rest switched their attention to the Parisian avant-garde, Ede continued to be an appreciative patron and customer, displaying his Wallises with suitably vernacular chairs and tables, pots and pebbles, in the arty domestic roomscapes of Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge.

Art history has upheld their estimate of Wallis ever since. Fixed in his reputation like a fly in amber, Wallis has remained the humble fisherman with a simple understanding, our conduit to the elemental, primitive, authentic or the simply ‘real?’ (Ben Nicholson’s appraisal). Ede thought him an ‘innocent painter,’ who ‘lived’ his painting and worked ‘unconsciously,’ going back into his memory to paint the glory days of the Cornish fishing industry.

The intention of an exhibition at Kettle’s Yard, now online until further notice, is to step away from a century of middle-class cultural appropriation and return the devoutly Bible-reading working class Wallis to something closer to his own voice and motivations. For Wallis was a little more knowing, operating in a town full of professional and amateur marine painters.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Sensing that his unexpected new patrons set store on his own ‘unknowingness’, he painted mostly ‘what use To Be’, the tall ships and brigantines of his own Victorian past, and he owned a crib that was probably given to him by Nicholson, In the Wake of the Wind Ships by F. W. Wallace (1927). Some of his pictures bear crazy signatures in mixed-up capitals and lower case, but he signed his work more frequently and legibly and his letters to Ede are tidily formal.

He wrote reassuringly to him (punctuation and spelling corrected): ‘The most you get is what used to be, all I do is out of my memory’ and ‘I never see anything I send you now, it is what I have seen before. I am self taught so you cannot like me to those that have been taught both in school and paint. I have had to learn myself. I never go out to paint nor I never show them’.

In little seascapes, such as Ship with seven men, net and gulls or Motor vessel mounting a wave, his pitching craft, wind driven like bits of twig on foaming turbulence or sailing effortfully uphill on a 45˚ blue-grey gradient, compel our careful looking.

The misshapen scraps of wood, packing case and cardboard on which he painted were cut into even more irregular shapes that generate tectonic shifts and forces within the picture plane, so that his condensing and abstracting became a kind of aerial mapping that Peter Lanyon would claim for his own. His low, reductive palette of house and ship paint was deliberately chosen, for he stated: ‘I do not put collars what do not Belong.’

By these small redrawings, we begin to understand Wallis as a potential innovator for British Modernism and not a stepping-stone landed upon by more starry household names. It’s a complicated procedure, of commodification re-commodified for a new zeitgeist, but a laudable one.

‘Alfred Wallis Rediscovered’ at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, can be viewed online — www.kettlesyard.co.uk

Credit: Winifred Nicholson, Cyclamen and Primula, 1923. Oil on board, 50 x 50 cm. Image courtesy of Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

In Focus: The radiant, sunlit work by the artist who inspired the founder of Kettle's Yard

Collective nouns for birds

We celebrate our favourite collective nouns for birds, from the weird and the wonderful to the most curious.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson