In Focus: The artist whose masterpiece was voted Norway's national painting, finally getting the recognition he deserves elsewhere

Caroline Bugler is spellbound by the Scandinavian landscape painter’s magical evocation of fjords, villages and mountains.

Norwegian art is having a moment. It all started four years ago, with the National Gallery’s show of Peder Balke’s weird and wonderful landscapes. Then, Nikolai Astrup’s rural idylls went on display at Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2016. Dulwich has now followed this up with Harald Sohlberg’s mystical visions of the Norwegian countryside and, hot on its heels, an exhibition devoted to Edvard Munch, Sohlberg’s contemporary, opened this week at the British Museum.

Munch’s art is famous all over the world — The Scream is an image so universal that it’s spawned an emoji — but Harald Sohlberg’s work is largely unfamiliar outside Norway. Part of that is because the Norwegians have kept his paintings to themselves; with the exception of a solitary example in Chicago, there is not a single picture by him in a public collection outside his native country.

This exhibition gives us a chance to see why the Norwegians love him so much that they voted one of his pictures — the magnificently moody Winter Night in the Mountains (1914) — their national painting. The pictures are arranged broadly chronologically, starting with Sohlberg’s early years and training and a few of his Symbolist pictures, including some very odd mermaids.

Although Sohlberg mostly chose to focus on the Norwegian landscape — all the scenes he painted were within a 20-minute walk of his home in Oslo and later in the village of Røros — his art was not insular. He spent some time training in Paris and Denmark and would have been familiar with the work of European Symbolists such as Gauguin. He shared their fin-de-siècle predilection for dreaminess, mystery and melancholy.

Take Summer Night in the first room, which he painted in 1899 to celebrate his engagement. It’s a moody, romantic scene. The table on the balcony is set for two. Wine has been poured and drunk, but the chairs are pulled back from the table, so the implied spectators of the stupendous view over a lake at dusk are absent. This absence of human figures is typical of Sohlberg’s landscapes.

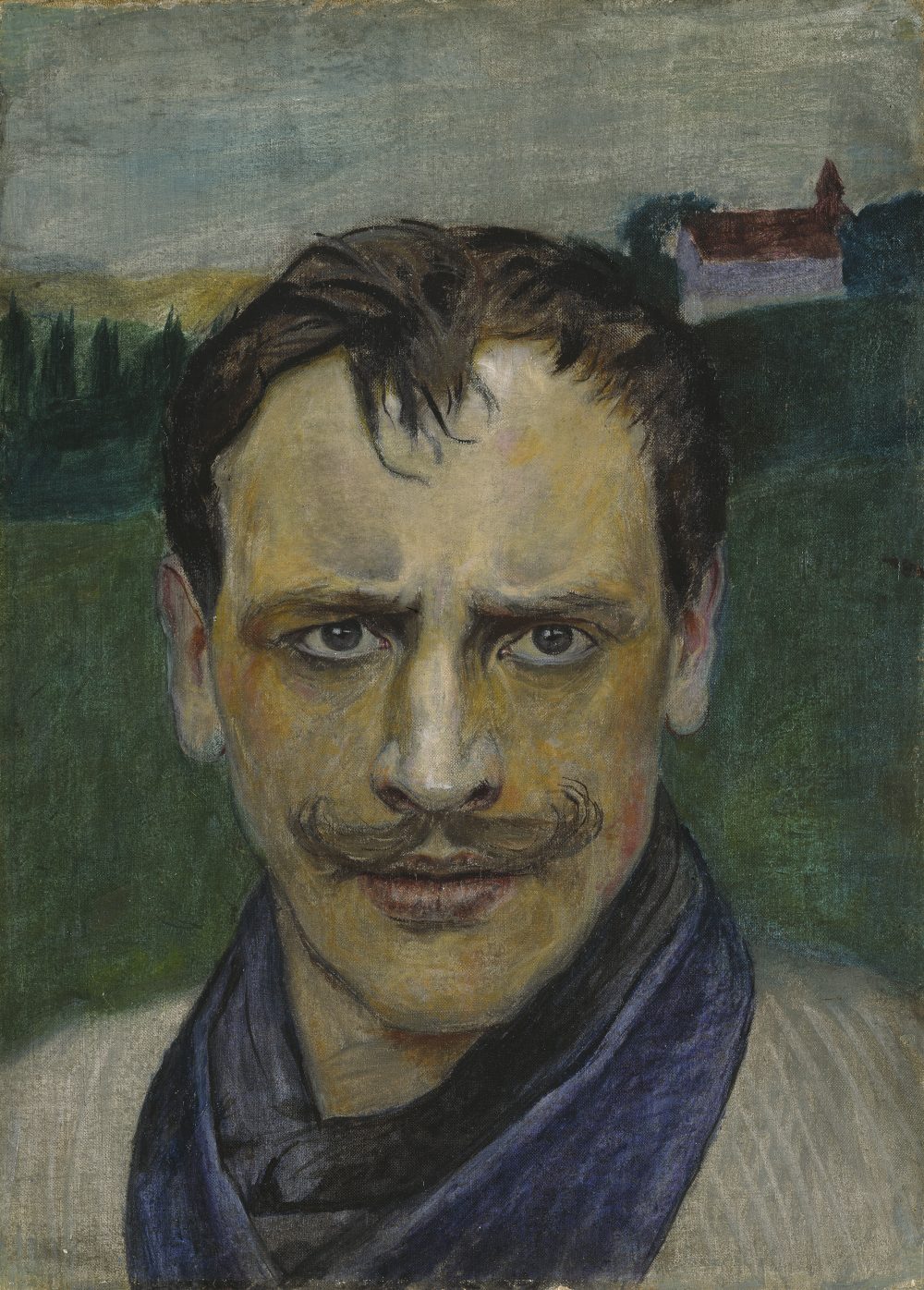

It’s not that he couldn’t paint them. A haunting self-portrait and a room full of academic drawings and prints reveals that he was a master of anatomy and a skilled portaitist, but he simply preferred to let houses stand in for humans in his landscapes.

Thus, in The Fisherman’s Cottage (1906), we see an isolated white house glimpsed through a screen of dark trees, its lit windows like eyes staring out over a cold, dark lake. This is landscape as a living, breathing thing in its own right.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

When Sohlberg came to paint the old mining town of Røros, where he lived from 1902 to 1905, he chose to gloss over the uglier aspects of creeping industrialisation. The town was actually filthy because of the smelting works, but it was the colourful wooden houses, the snow and the dusk that captured his eye rather than the grime.

The church had a particular presence. In Night (1904), it looms out of the dusk, a single window glowing yellow against the blues; all around lie scattered gravestones. Sohlberg was very taken with an inscription on one of the crosses that declared ‘We will not forget’. Clearly, everyone had forgotten, for the graveyard lay sad and neglected.

Any show at Dulwich has to contend with Soane’s strange little mausoleum in the centre of the exhibition space, but the curators have turned this to an advantage by placing in it a newly commissioned work by Mariele Neudecker — a tank, like an aquarium, containing what appears to be a miniature submerged forest, rather like the dense Nordic woods in the Sohlberg paintings that inspired it.

The installation is titled And then the World Changed Colour: Breathing Yellow and, as you walk round it, you can see how the yellow light filtered through the stained glass of the mausoleum’s windows changes as it is refracted into this shadowy world.

The yellow of Neudecker’s work picks up on the sulphurous glow of the skies in some of Sohlberg’s landscapes. He may have been relatively faithful to the topography of the Norwegian countryside and showed a sharp eye for architectural detail, but his use of colour sometimes seems more symbolic than naturalistic.

At a time in which Whistler was painting his twilit ‘Nocturnes’, Sohlberg was producing ‘Andantes’ — canvases in which colour conveys mood. There are dawns and dusks where the horizon gleams with yellows and oranges that look almost garish.

His soft mauves, purples and blues are poetic and misty, especially when they wash over the mountains in the monumental canvases in the final room, expressing a sense of awe in the face of Nature’s majesty. ‘The longer I stood gazing at the scene,’ he wrote of the mountains at Rondane, ‘the more I seemed to feel what a solitary and pitiful atom I was in the endless universe.’

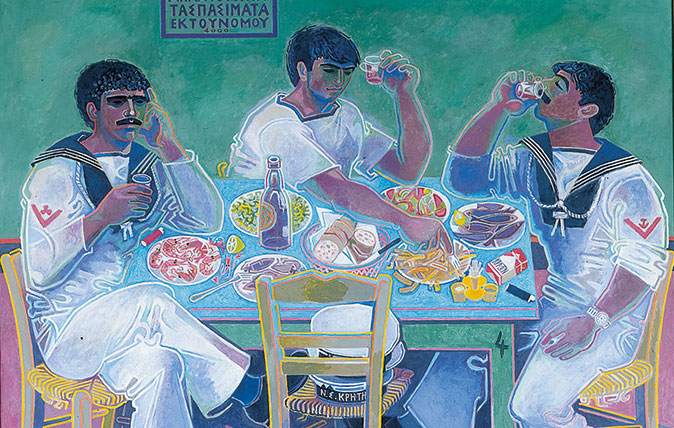

In Focus: The charmed life of Paddy Leigh Fermor and friends in Greece

The iconic writer Paddy Leigh Fermor and two of his friends in Greece – both artists, one a local man and

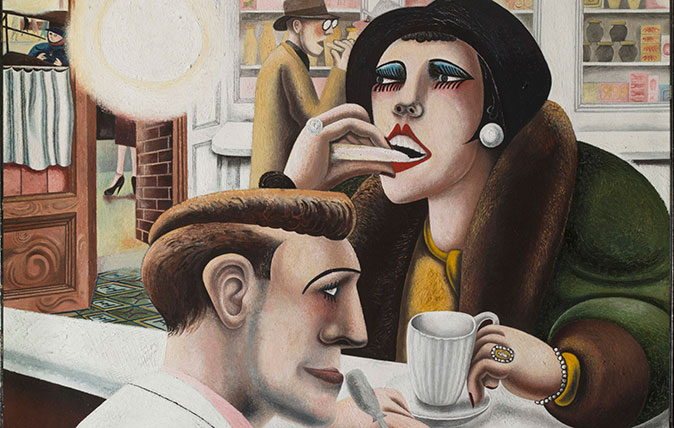

In Focus: The evocative, sensual masterpiece created in the wake of the First World War

Edward Burra was too young to have fought in the First World War, but his powerful oil painting The Snack

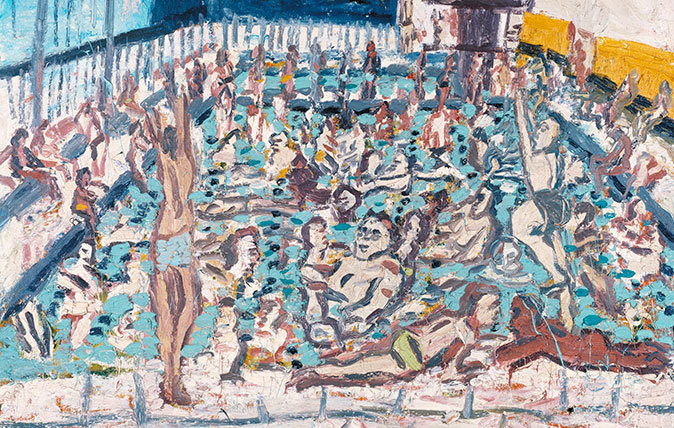

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

In Focus: The 160-year-old ‘Photoshopped’ picture which shocked Victorian England

An exhibition looking at four of the giants of Victorian photography has at its centre a remarkable work by the

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill