How Cartier became ‘the jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers’

In the early 20th century, Cartier creations adorned everyone from monarchs and superstar actresses, to American ‘Dollar Princesses’. A blockbuster exhibition at the V&A, featuring more than 350 objects, plans to chart the maison's legacy.

Above the chimneypiece in the White Drawing Room at Buckingham Palace, Queen Alexandra’s official portrait by François Flameng sparkles with an array of impressive jewels. Painted in 1908, the youthful-looking Queen Consort (who was actually 57 years old by the time her husband, Edward VII, was crowned) appears almost fairy-like, surrounded by a halo of diaphanous gauze and wearing the glittering symbols of her newfound status — Queen Victoria’s small diamond crown, the star and blue riband of the Order of the Garter and, notably, a grand collier résille, made for her by Cartier in 1904. Having it portrayed alongside the formal jewels of British chivalry in this way shows exactly how highly the Queen regarded the Parisian jeweller’s striking creation.

For well over a century, Cartier has been regarded ‘the jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers’, a term famously coined by the sybaritic Edward VII, who was so fond of the maison’s finery that he encouraged Pierre and Louis Cartier (the enterprising grandsons of the firm’s founder, Louis-François) to establish a branch in London in time for his coronation in 1902. When Cartier duly opened its first British boutique on New Burlington Street (it would eventually be run by the youngest Cartier brother, Jacques), the family’s efforts were rewarded with a commission for 27 sparkling tiaras for the coronation and an appointment as official jeweller to the Crown — the first and only foreign jeweller to be so honoured. Other royal households soon followed suit and, between 1904 and 1939, Cartier supplied extraordinary jewels to 15 different monarchs, including Alfonso XIII of Spain, Carlos I of Portugal and Paramindr Maha Chulalongkorn of Siam, who once purchased an entire tray of bracelets set with precious gemstones from Cartier in Paris worth US $450,000 (roughly $15.2 million today).

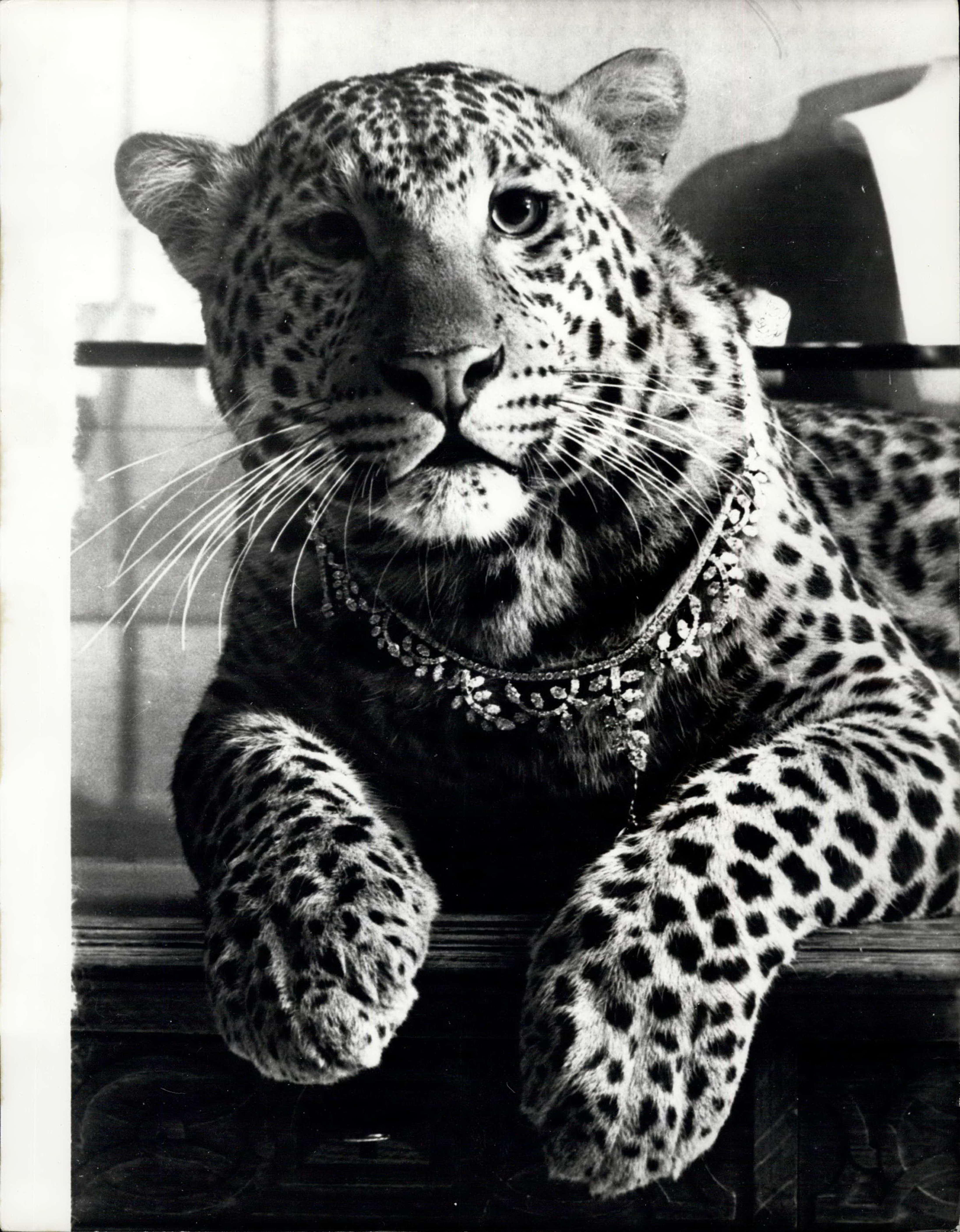

In 1925, Rina the panther — an animal synonymous with Cartier as far back as 1914 — was brought in to model a diamond and emerald saltire necklace

The enormous industrial, economic and cultural changes that took place at the dawn of the 20th century proved hugely formative for Cartier: its fortunes skyrocketed as the preferred jeweller of the smart set. ‘Compared with the hermetic feeling of the Victorian period, the Edwardian era saw a huge increase in conspicuous consumption, international travel and an ever more theatrical and opulent social life — not only at Court, but in new recreational spaces, including luxury hotels such as The Ritz, which provided ample opportunities to show off dazzling jewels,’ says author and social historian Martin Williams. ‘Furthermore, there was a great passion for the French decorative arts, which Cartier absolutely made its own with intricate garland-style jewellery, inspired by the French architecture of the 18th century. Wearing Cartier effectively became a symbol of your status and excellent taste, as indivisible from the Edwardian or Belle Époque notions of luxury as Worth in the field of couture fashion or Fabergé for artistic objets.’

Cartier’s popularity among the wealthy elite also grew thanks to the company’s inventive craftsmanship, which pioneered the use of novel materials, such as platinum. At a time when elaborate tiaras, epaulettes and corsages were de rigueur at Court, the silvery-white metal lent Cartier’s jewels a strength and delicate airiness that allowed diamonds to shine without adding weight. It’s hardly surprising, then, that Queen Alexandra turned to Cartier for her ethereal, web-like collier, with its detachable emerald and ruby drops, or that her husband commissioned Cartier to produce a romantically curlicued tiara of platinum and gold for his other great love, his long-term mistress Alice Keppel.

Wallis Simpson owned more than 80 Cartier creations including a diamond onyx panther bracelet (below), that sold for £4.5 million in 2010, and her emerald engagement ring — sourced in 1930s Baghdad by Jacques Cartier

Other notable Cartier clients included the cultural patron Constance Gladys, Countess de Grey and the Marchioness of Ripon — who did much to open up High Society to new experiences, such as dining at restaurants, where jewels could be more openly admired — and the ultra-wealthy Consuelo Yznaga, Duchess of Manchester, one of the American ‘Dollar Princesses’ who cut a stylish dash through Britain’s previously fusty nobility and increased its appetite for glamour.

So carefully and discreetly nurtured were the maison’s relationships with the era’s highest profile women that it was to Cartier, naturally, that many of them turned (including the Duchess of Bedford, the Duchess of Marlborough and superstar actress Ellen Terry) when, in 1918, they needed a space to display jewels intended for an auction in aid of children’s charities — the company proudly put their pieces on display at its new premises at 175, Bond Street (still its London flagship today). Long before the arrival of television or cinema, observes Pierre Rainero, Cartier’s director of image, heritage and style, these women were the celebrity influencers of their day: ‘The growing independence and power of these women in Society helped Cartier a lot. It came to be seen as a jeweller at the very forefront, with its craftsmanship, the quality of its pieces and with its daring deci- sions in terms of design.’

With the advent of the Jazz Age, Cartier’s enthusiasm for the avant-garde only increased, attracting a new slew of well-heeled clientele, including affluent Americans. Proto-Art Deco jewels, featuring futuristic, architecturally inspired shapes and innovative materials, such as blackened steel, began appearing in the house’s repertoire as early as 1911 and its first intriguing Mystery Clock, which had no visible mechanism and seemed to ‘float’ in the middle of a rock-crystal base, had its debut in 1912 — the brainchild of an ingenious young horologist, Maurice Couët, hired by Louis Cartier. Only two years later, an unusual ladies’ wristwatch bearing a ‘leopard print’ pattern of diamonds and onyx ushered in a new house motif that would develop into one of the most recognisable jewellery designs of all time — the Cartier panther.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

American heiress Barbara Hutton's necklace of Burmese jade

By the 1930s, kaleidoscopic gemstone jewels had replaced white-diamond pieces on the necks, earlobes and wrists of the most celebrated socialites. Pioneered by Jacques Cartier, who frequently travelled to India on gem-buying trips, the jaw-dropping emerald, ruby and sapphire ‘tutti frutti’ pieces were collected by the Singer sewing-machine heiress, Daisy Fellowes, once deemed ‘the most fashionable woman in the world’ by the poet Jean Cocteau. The Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton, who enjoyed co-ordinating the colour of her car to the jewels she wore each day, was given an exquisite jadeite Cartier necklace by her father, Franklyn Laws Hutton, to celebrate her 1933 marriage to Prince Alexis Mdivani (in 2014, it would set a record as the most expensive jade jewel ever sold at auction).

Later still, the American-born Duchess of Windsor, Wallis Simpson, made international headlines wherever she went, often adorned in one of more than 80 Cartier creations she owned, including a vivid amethyst and turquoise bib necklace of 1947 or a panther brooch with a 152.3 carat-sapphire from 1949, which she liked to wear on her shoulder.

Now, a new exhibition at London’s V&A Museum will shine a spotlight on Cartier’s illustrious design heritage and its journey to becoming a jewellery tour de force. Titled simply ‘Cartier’, the retrospective will include the largest display of the maison’s work in the UK for almost 30 years, with more than 350 objects, including hitherto unseen drawings from the Cartier archives and spectacular pieces lent by the Royal Collection. Highlights include the Manchester Tiara, crafted for Consuelo Yznaga using more than 1,400 of her own diamonds; the Hutton-Mdivani jadeite necklace; a selection of emblematic panther jewellery; and an opal tiara, com- missioned by the Marchioness of Hartington — née Kathleen ‘Kick’ Kennedy — in 1937 and shown in public for the first time. ‘There is so much richness to the Cartier story,’ says co-curator Rachel Garrahan. ‘I hope visitors will feel they leave with a deeper under- standing of the extraordinary combination of qualities that made Cartier so pioneering in terms of design and technique — and in creating an image of itself that lives on today.’ Indeed, by making itself synonymous with quality, originality and a coterie of remark- able women, Cartier has transcended from being ‘jeweller of kings’ to being jeweller of Queens, style mavens and luxury lovers around the world. Long may it reign.

‘Cartier’ at The Sainsbury Gallery, V&A Museum, runs from April 12–November 16.

Kim Parker is a London-based journalist specialising in jewellery, fashion, and watches. She has more than 20 years’ experience in the luxury industry and, alongside Country Life, has written extensively for titles such as Harper’s Bazaar, Town & Country, The Times, and The Telegraph. When she’s not researching the latest and greatest jewellery finds, she’s happiest on horseback.

-

'Fences have blocked wildlife corridors, causing the wildebeest migration to collapse from 140,000 individuals to fewer than 15,000': Is the opening of the Ritz-Carlton in Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve a cause for celebration or concern?

'Fences have blocked wildlife corridors, causing the wildebeest migration to collapse from 140,000 individuals to fewer than 15,000': Is the opening of the Ritz-Carlton in Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve a cause for celebration or concern?In Kenya's iconic Masai Mara region tourism is an important and necessary part of the economy, but the arrival os several large hotel groups — including Ritz-Carlton — have some on edge.

-

‘I get all twitchy when I see people wearing something that really doesn’t belong’: A watch for every summer occasion

‘I get all twitchy when I see people wearing something that really doesn’t belong’: A watch for every summer occasionThere’s a watch for every social summer occasion, from the Mediterranean to muddy festivals. Chris Hall selects some of his favourites.

-

‘I get all twitchy when I see people wearing something that really doesn’t belong’: A watch for every summer occasion

‘I get all twitchy when I see people wearing something that really doesn’t belong’: A watch for every summer occasionThere’s a watch for every social summer occasion, from the Mediterranean to muddy festivals. Chris Hall selects some of his favourites.

-

Coco's crush: Chanel's century-long love affair with Britain and its men

Coco's crush: Chanel's century-long love affair with Britain and its menFor the past 100 years, Chanel — the person and the brand — has left an indelible mark on the UK and its cultural institutions. Amie Elizabeth White takes a look at how the relationship came to be.

-

Canine muses: The English bull terrier who helped transform her owner from 'a photographer into an artist'

Canine muses: The English bull terrier who helped transform her owner from 'a photographer into an artist'In the first edition of our new, limited series, we meet the dogs who've inspired some of our greatest artists.

-

The successor to the 'most beautiful car of the 20th century' is smooth, comfortable... and ends up highlighting everything that's wrong in car design today

The successor to the 'most beautiful car of the 20th century' is smooth, comfortable... and ends up highlighting everything that's wrong in car design todayThe DS No. 4 traces its lineage back to the Citroën DS, a car so extraordinary that people described it as looking 'as if it had dropped from the sky'. And while the modern version is more friendly to the earth, says Toby Keel, it's also worryingly earthbound.

-

Richard Rogers: 'Talking Buildings' is a fitting testament to the elegance of utility

Richard Rogers: 'Talking Buildings' is a fitting testament to the elegance of utilityA new exhibition at Sir John Soane's museum dissects the seminal works of Richard Rogers, one of Britain's greatest architects.

-

‘The perfect hostess, he called her’: A five minute guide to Virgina Woolf’s ‘Mrs Dalloway’

‘The perfect hostess, he called her’: A five minute guide to Virgina Woolf’s ‘Mrs Dalloway’To mark its centenary, Lotte Brundle delves into the lauded writer’s strange and poignant classic, set across a single summer’s day in 1920’s London.

-

300 laps, thousands of tires, 24 hours of non-stop racing: Up close and personal at Le Mans 2025

300 laps, thousands of tires, 24 hours of non-stop racing: Up close and personal at Le Mans 2025At this year's iconic 24 Hours of Le Mans, British car manufacturer Aston Martin returned to the race's top category — and they invited writer Charlie Thomas along for the ride.

-

Richard Mille: The man who went from carving watches out of soap to making timepieces for Rafael Nadal and Lando Norris — and built a £1bn business in the process

Richard Mille: The man who went from carving watches out of soap to making timepieces for Rafael Nadal and Lando Norris — and built a £1bn business in the processA new coffee table book by Assouline celebrates one of today’s most daring and innovative watch brands.