How Britain's regional auction houses are taking on the mighty duopoly — and pulling off coups as they do so

As Britain’s leading metropolitan auction houses cut their regional activities, their provincial counterparts are doing better than ever, says Emma Crichton-Miller.

As my car takes the winding road off the main A339 towards Donnington Priory, Siri announces my destination, ‘Dreweatts 1759’. The date is absolutely part of this well-known auction brand. Only Sotheby’s, which traces its origins back to 1744, predates it.

Dreweatts, founded by Thomas Davis, a cabinetmaker and land agent from Abingdon, Oxfordshire, is one of a sprawling regional network of auction houses — Sworders (1782), Mallams (1788), Cheffins (1825), Lyon & Turnbull (1826), Woolley & Wallis (1884) — that sprang up from the late 18th century to serve a growing appetite for this particular method of exchange. Industrial capitalism had created the need to pass stuff on, from one generation to the next, or from the debt-ridden to the newly rich.

By the 20th century, there were auction houses in almost every market town, selling everything from houses to livestock to furniture and fine art. Today, a handful of names — the London duopoly Christie’s and Sotheby’s with their near-neighbours, the more generalist Bonhams and the more specialised Phillips — dominate the higher ends of the market.

Meanwhile, the fortunes of the mass of regional houses has risen and fallen repeatedly as economic circumstances and peoples’ habits and tastes have changed.

In 2020, however, as a new decade opens, the situation for regional auction houses in Britain is buoyant. Their names increasingly appear in the media attached to record auction prices, rediscovered masterpieces or prestigious country-house sales. A number has carved out specialisms that have seen the ambitions of smaller houses grow, leading some, in pursuit of an international, moneyed clientele — Lyon & Turnbull, Sworders and Dreweatts, for example — to open London offices.

Others, including market-leader Woolley & Wallis in Salisbury, have maintained strong local roots, as well as reaching out internationally. In a perhaps surprising departure, new auction houses have also opened, taking up the local slack left by the angling of these older institutions for more specialised or far-reaching business.

All have seen their businesses change radically in the past 20 years, as the internet has opened access universally, not only to auction catalogues and to bidding, but also to the vast hinterland of information that had previously been the sole preserve of scholars and dealers.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

When you arrive at Dreweatts’s picturesque headquarters, on the outskirts of Newbury in Berkshire, within easy reach of London and Oxford, it’s hard to believe that the business in its current incarnation is less than three years old. Donnington Priory dates back to 1393, the current building to 1655. It was bought by the company, then Dreweatt, Watson & Barton, in 1978.

Dreweatts itself is now owned by London Art advisory and valuations firm Gurr Johns, but George Bailey, the current chairman, is sanguine about the myriad structural evolutions that the serene continuity of name disguises: ‘It’s a good, old fashioned name,’ he says; moreover, many of the specialists have been with the business a long time. Indeed, the new managing director, Jonathan Pratt, who joined 18 months ago from Bellmans, reveals that his very first job was at Dreweatts in the 1990s.

For both, what has been essential to their current confidence has been the decision to focus on the traditional categories of a fine-art auction house, such as Fine Art, Clocks, Silver, Ceramics and Glass, Jewellery, Fine Furniture, Asian Art and so on. Although Sotheby’s and Christie’s cream off the very top end of this market, the dramatic withdrawal of Bonhams and Phillips from the regions since the late 1990s has created an opportunity for smaller, local auction houses to step into the very broad middle market, accessing treasures in their immediate hinterlands. The strategy of Dreweatts, within this market, has been to aim high with a mix of well-presented, decorative interiors sales, single-owner or country-house auctions and some highly curated specialist events.

‘We would like to be really good at what we do,’ Mr Bailey says. ‘We have brought in new specialists, we present well, we market well and we attract a strong buying base.’ Mr Pratt adds: ‘We now have three academic-paintings researchers.’ In addition, unlike some auction houses, Dreweatts has the facilities to display things well. ‘We can dress things up,’ points out Mr Pratt, gesturing to the beautifully restored Georgian rooms.

The company will offer, in March, the Collection of Sir William Whitfield CBE, the sale of contents of a Queen Anne House put together over 40 years, for which Dreweatts is collaborating with Colefax & Fowler to create complete room settings. ‘We won this sale because other auction houses could only take one or two objects, whereas we will take it all and do a really nice job,’ explains the chairman. His CEO confirms that, as do all the leading auction houses, Dreweatts invests in well-produced catalogues, with thorough research and good photography of every lot, as well as trying to reduce its carbon footprint by reviewing the production processes. The catalogue is as much a demonstration of values and a declaration of intent as it is a selling tool.

So far, the strategy seems to be working. At the sale of the collection of Eustace Gibbs, 3rd Baron Wraxall, brother of the former owner of Victorian Gothic-Revival Tyntes-field, Somerset, the careful placing within the catalogue of a limed-oak George VI Coronation chair with a matching limed-oak Coronation stool, upholstered in green velvet, within a section of the sale devoted to royal memorabilia, enabled the modest lot (estimated £100–£200) to achieve £4,800 (including 25% buyer’s premium, plus VAT).

Other notable triumphs include a delicate Chinese celadon Dragon and Phoenix vase from the Yongzheng period (1678–1735), which soared to £290,000 on a £6,000–£8,000 estimate; and a beautiful 2ft-high pink-marble carving of a female nude, dated 1928, by the sculptor John Skeaping (1901–80), Barbara Hepworth’s first husband, which sold to Cork Street dealership Browse & Darby for £90,000 (£111,600, including premium) in May 2017, creating a new record for the artist.

‘We are all chasing the high-value pieces that are fresh to market,’ Mr Bailey remarks. Although they cannot compete with Sotheby’s and Christie’s, local auction houses will certainly compete with the best of the rest.

When I try to catch John Axford, the new chairman of Woolley & Wallis and a familiar face to fans of the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow, he is in Rome, visiting a client. Mr Axford has been with the auction house for 26 years. It’s the leading provincial salesroom in the country, responsible for 11 of the 14 lots to have made more than £1 million outside London.

The first was the Alexander vase, a curvaceous Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) blue and white vessel bought by William Cleverly Alexander in 1876 for 66 gns and then by the vendor’s ancestor for £10 in 1900. It was recognised in a routine valuation as valuable and, when the vendor declared that it required a specialist Chinese sale, Mr Axford founded Woolley’s Asian art department on the spot. In 2005, the vase made £2.6 million hammer price, more than £3 million with buyer’s premium, from a modest estimate of £250,000.

Since then, the Asian department has become so successful that its main website is in both English and Chinese. Another coup was the sale of The Pelham Water Buffalo, an Imperial spinach-green jade piece of the Qianlong period (1736–95), found wrapped in a 1940 newspaper. It sold in 2009 for £3.4 million hammer, then the world record for a jade carving. Mr Axford comments: ‘The things we do, we want to do as well as anyone. We occupy the top slot.’

Tribal Art is another niche his company fills successfully, having worked in 2016 with the dealer Entwistle to sell, by private treaty, a 16th-century Benin bronze head for a world-record price for African art. ‘The really big change came with digital photography and the internet,’ Mr Axford comments. ‘Some 95% of our buyers for Chinese art are in China and Hong Kong. We have sold important collections from Lisbon, Rome and South Africa and we source pieces in Canada and the US. We just happen to be in Salisbury.’

For Lyon & Turnbull, based in Edinburgh, the catalyst for transformation was the withdrawal of the London-based auction houses from the regions. Gavin Strang, managing director, points to the moment in 1999 when a group of ex-Phillips auctioneers, including his current vice-chairman, Paul Roberts, acquired the Lyon & Turnbull brand name from a business that was then defunct, with the intention of creating an international auction house for Scotland.

‘We inherited almost nothing but the name. We didn’t want to be generalist. We wanted to have specialist sales and to add value to the middle market.’ Mr Strang defines that as £1,000–£50,000, ‘or even £1,000–£20,000. That is where we mostly operate’.

As well as having a predictable strength in Scottish pictures, the house also specialises in the sale of collections. Christopher Forbes gave it the contents of Old Battersea House to sell in 2011 and, in 2012, Donald and Eleanor Taffner shipped their renowned Glasgow School collection to Edinburgh. Lyon & Turnbull cross-market with Philadel-phia auction house Freeman’s in the US and rely on a mix of excellent personal relationships with clients and the sheer effort put in to marketing, display and the sale itself. On the day, it has three online platforms, as well as the saleroom. The demise of Christie’s South Kensington has opened the middle market in London, so Lyon & Turnbull has also taken the opportunity to do pop-up sales in London.

Sworders Fine Art Auctioneers, based in Essex, has seized this opportunity, too. Chairman Guy Schooling, who has overseen the house’s transformation from a three-man operation about 30 years ago to its current position in the top five regional houses, ascribes part of that to the Chinese market. ‘About 15 years ago, we found suddenly that there were Chinese buyers on the phone and Chinese pieces were making 10 times their estimates.’

At that point, such pieces were still easy to find, overlooked, in British collections. Even last November, Sworders sold a Chinese imperial Qianlong famille rose vase that was bought for only £1 in a charity shop for £484,000 (with premium). Today, the firm has someone scouting for works in Taiwan, mainland China and Hong Kong for six weeks every year and, since 2019, conducts its Asian sales in London.

Another boost has been the decision to create specialist sales that ‘helped draw pieces to us, which then made four to five times what they would have made in a general sale’. Areas of expertise are 20th-century British and European Art, 20th-century design, jewellery and Arts and Crafts.

As Mr Schooling says: ‘You have constantly to evolve. It is a very active market. We are always having to find new areas to explore.’ No longer sleepy, nor even very regional, the provincial auction houses seem in rude health, open to the world and the future.

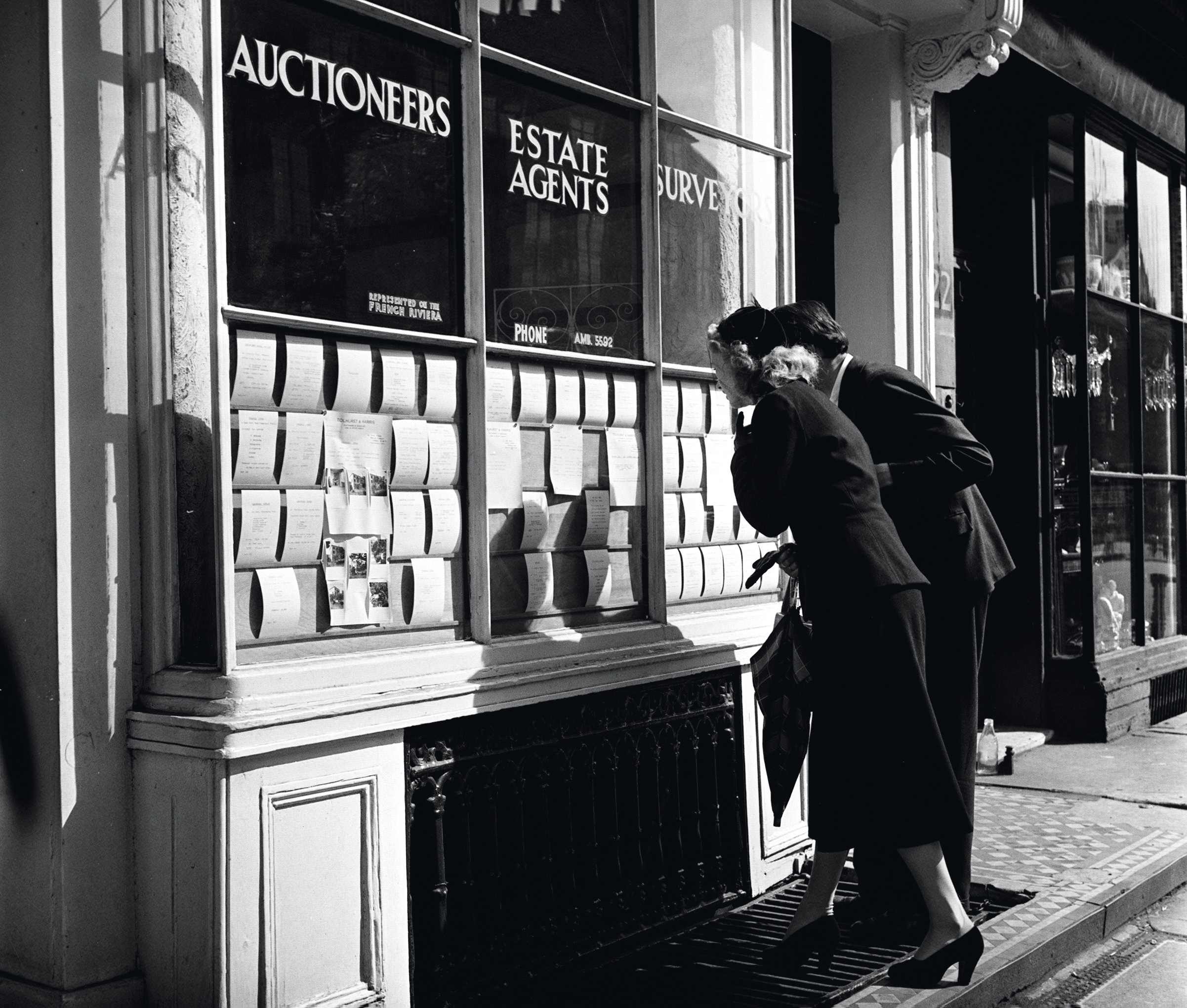

Credit: Getty Images/Popperfoto Creative

The curious tale of how estate agents came to run the British property market

From gentlemen farmers to auctioneers of Nazi wine, Roderick Easdale traces the birth of British estate agents.

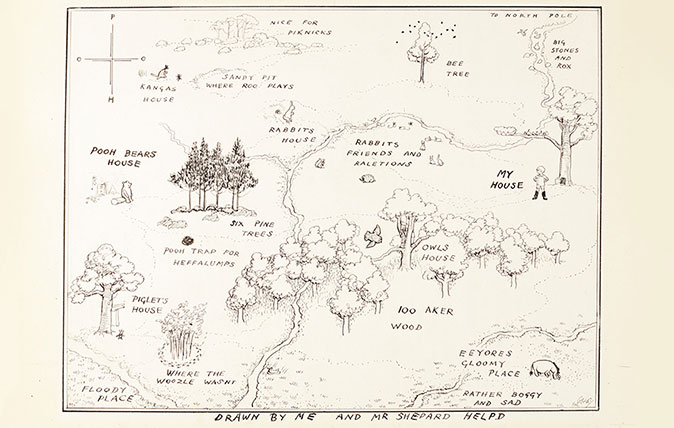

E.H. Shepard's original map of the Hundred Acre Wood from Winnie-the-Pooh is up for auction

This delightful piece of literary and artistic history by E. H. Shepard is to be auctioned for the first time

Credit: Leonardo da Vinci

The awkward questions that still need answering about Da Vinci's $450m Salvator Mundi

The dust has now settled following the $450 million sale of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi. But there are still

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of them

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of themThe Arts and Crafts movement was an international design trend with roots in the UK — and lots of buildings built and decorated in the style have since been turned into hotels.

By Ben West

-

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in Kent

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in KentGrade I-listed Holwood House sits in 40 acres of private parkland just 15 miles from central London. It is spectacular.

By Penny Churchill