Gordon Beningfield: A celebration of the artist and champion of the countryside

Twenty years after the death of Gordon Beningfield, Octavia Pollock revisits the work of the artist and countryside champion.

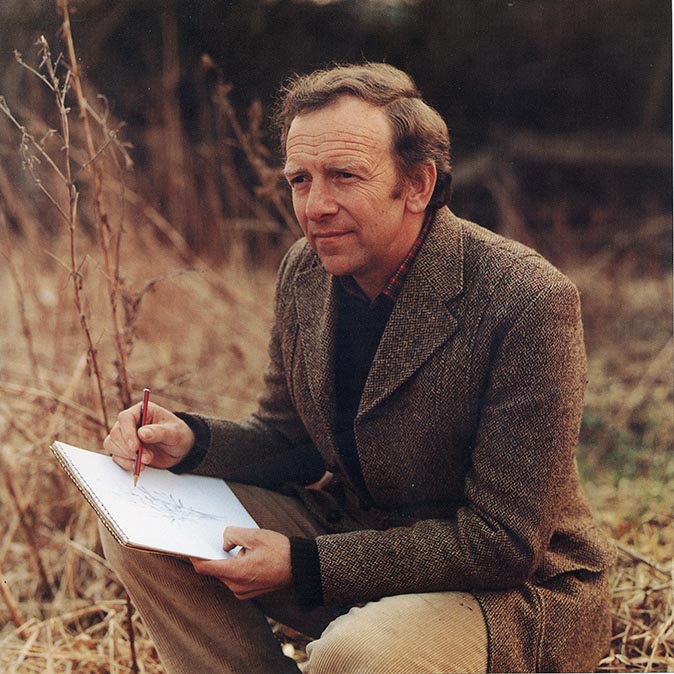

Butterflies lead a merry dance across the water meadows between Great Gaddesden and Water End in Hertfordshire to the cottage where Gordon Beningfield, artist and countryside champion, lived until his untimely death 20 years ago, aged 61. Over homemade marmalade cake, his widow, Betty, and their friends Dennis and Ann Furnell reminisce about his humour, his – entirely unmechanical – love for classic cars and his genius for forging relationships with everyone, from the Queen Mother to her gamekeeper. ‘If anyone needed to find us, they simply had to follow the laughter,’ says Mr Furnell of their many expeditions.

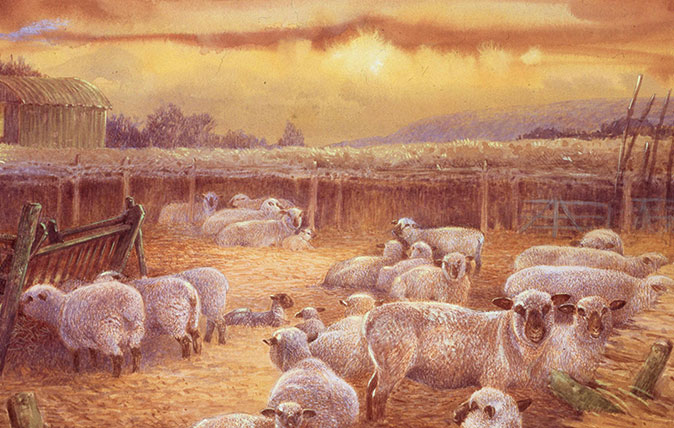

Beningfield’s paintings hang everywhere in the cottage: a South Downs shepherd with hut and crook, saturated in a golden evening haze; his three deerhounds, Rory, Bruce and Robbie; a longhorn cow scratching her ear. Outside, the garden is as much an extension of the countryside as ever, leading to the chalkstream that the artist, Mr Furnell and their friend Eric Morecambe restored: the comedian once caught a 6lb brown trout there.

‘We met dancing the jive,’ Mrs Beningfield remembers. ‘He was a Teddy Boy, with a velvet collar.’ She supported him ever afterwards and, with mutual friend Robin Page, completed Beningfield’s Vanishing Song-birds, the book he was working on at his death.

The skylark ‘became one of the most important birds to him,’ wrote Mrs Beningfield, ‘because as the song of the lark lessened and the countryside became quiet, it suggested to him that a great tragedy was taking place… as farming “progressed”, so he saw wildlife decline and songbirds vanish.’

Born within earshot of Bow Bells, Beningfield never forgot the ‘glorious impact of finding myself in the countryside’ when his family moved to Hertfordshire after his father’s work as a Thames lighterman dried up during the Second World War. His artistic skill was nurtured by his father, whom he would accompany on sketching expeditions on the crossbar of his bicycle, and his headmaster, who recognised where the boy’s talents lay and excused him from writing tasks, onerous to one with dyslexia, to paint.

Life as a gamekeeper tempted him, but, instead, he joined Faithcraft, a company that specialised in ecclesiastical art, and became absorbed by ‘the sheer richness of our heritage in church architecture’. He left his own mark with the superb engraved-glass windows in the Guards Chapel in London. ‘He could work with a glass cutter like other people work with a brush,’ says Mr Furnell.

Beningfield shared his interest in ecclesiastical art and J. M. W. Turner with Thomas Hardy, whose Wessex landscapes he frequently explored. Meeting Gertrude Bugler, whose mother had inspired the title character of Tess of the D’Urbervilles and who had played Tess on stage at Hardy’s request, was a joy. The paintings of Archibald Thorburn, the poetry of John Clare and the music of Vaughan Williams held a natural appeal.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

When he was 14, he encountered the work of Henry Moore and, after writing to express his admiration, received an invitation to visit. Beningfield’s own sculptural talent should be better known: his polished wooden fox and bronze longhorns glow with life.

The key to his skill was keen observation. His father told him: ‘Paint what you see, Gordon, paint what you see.’ Even quicksilver butterflies would imprint themselves on his memory. ‘He would take black-and-white photographs, but he could remember colours exactly,’ notes Mr Furnell.

Beningfield’s ecclesiastical training influenced his methods, glazing canvases with oil paints before adding watercolour to ‘create a sort of luminosity’ in the Victorian style. Some were shocked by the mixing of media, but, as he himself wrote: ‘Whoever produced good work just by sticking to the rules?’

‘His paintbox was such a mess of colours,’ remembers Mr Furnell of his habit of using a chunk of body colour and mixing it with watercolour. ‘Either you catch it before it moves or you move with it,’ Beningfield noted. ‘The wetness is useful to me because I don’t want hard edges.’ The detailed work – the edges of a butterfly’s wing or a goldfinch’s beady eye – he carried out with a tiny brush, building up minute strokes.

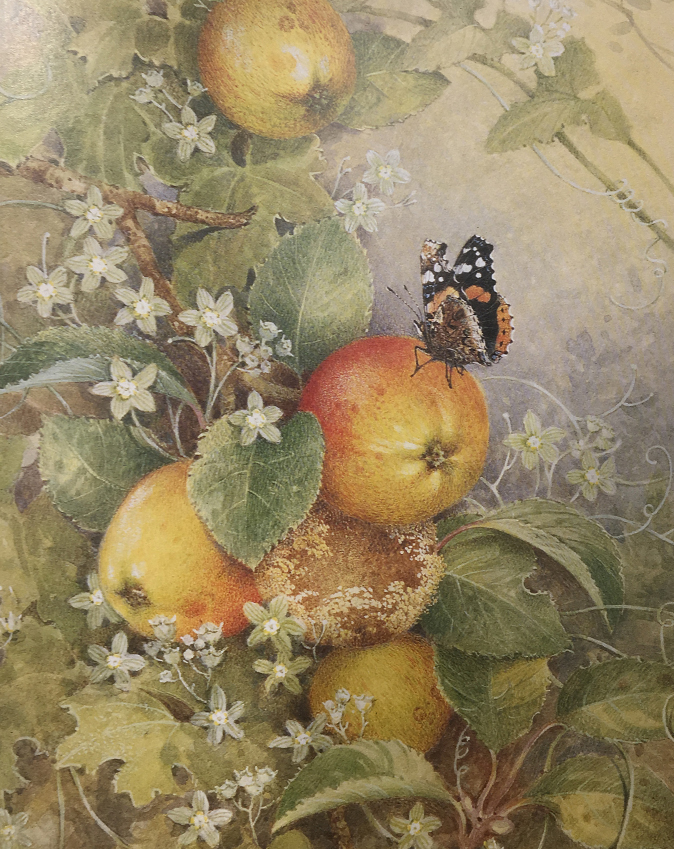

A countryman first, he wrote that ‘my pictures show them as you will see them in Nature’. An orange tip butterfly alighting on a red campion ‘is not a colour combination I would ever have invented for myself. It is something that I had to see’. Painting a shy snipe, he just ‘sat down quietly… and waited’.

Beningfield’s fame grew through his natural, informative radio and TV programmes. Clad as always in a tweed suit and tie, he knew and respected the farmers and was received as a friend, discussing changes in farming, the price of livestock, animal husbandry and the old ways.

Already a seasoned campaigner – against stubble burning, the ploughing of water meadows (‘we were threatened by an irate character with a pitchfork,’ remembers fellow crusader Mr Furnell), chemical farming and the practice of flailing hedges, ‘pure vandalism’ – his work as a presenter led to a practical demonstration of his belief that ‘there is no reason why good farming and conservation should be incompatible’.

‘We met when he interviewed me about my pet vixen for In the Country,’ remembers Mr Page. ‘He became my closest friend.’

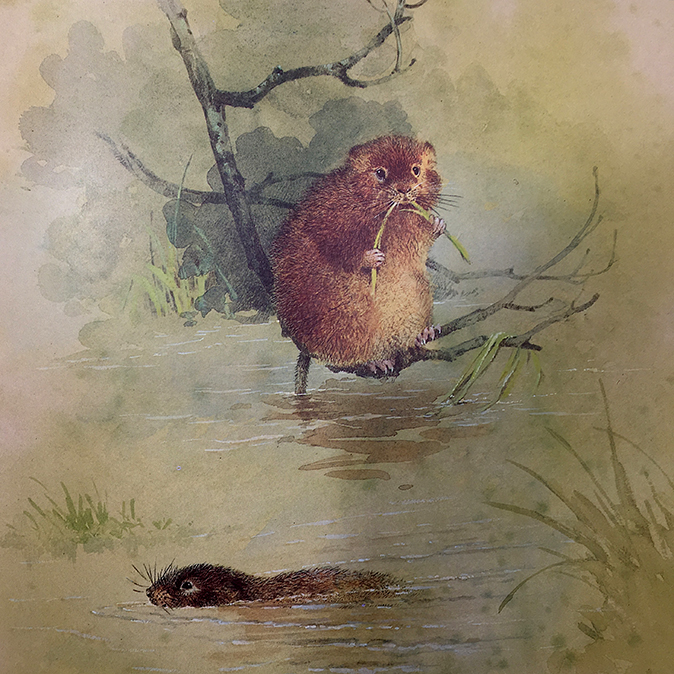

After abortive discussions with the RSPB about the damage caused by intensive farming – ‘we were told the future was nature reserves’ – they and Sir Laurens van der Post launched the Countryside Restoration Trust (CRT) in 1993. Now, 25 years later, it owns 14 farms. That first property, Lark Rise Farm in Cambridgeshire, has grey partridge, water voles, orchids and barn owls.

In his memory, the CRT has launched the Gordon Beningfield Dorset Farm Appeal, with Dame Judi Dench as patron, to buy a property in the county that he loved. He wrote in Hardy Country: ‘I would not want anyone to be complacent about the parts of Dorset that have so far escaped [large-scale cereal growing]… I am passionately concerned to make sure that it survives.’

Elsewhere, there’s still a long way to go. ‘He would say the biggest problem today is development, breaking up ecosystems so only small, unsustainable patches remain,’ says Mr Furnell. ‘The awareness is there, but not the action.’

Yet there is hope. His own corner of Hertfordshire, only 10 miles from the M25, is still rural, villages nestled among ancient estates. He appreciated the value of fieldsports: ‘What is being preserved on a sporting estate is, in effect, the nature of the landscape.’

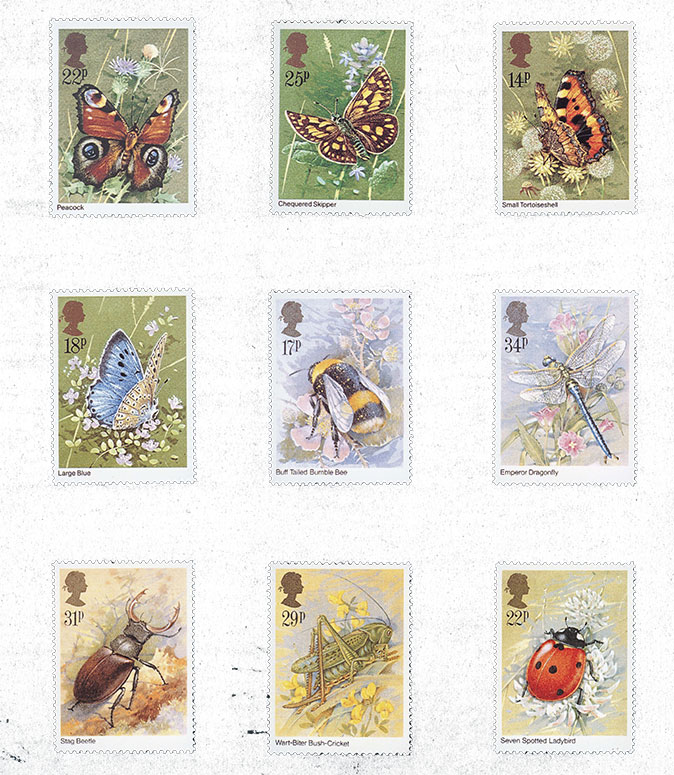

The artist served as president of Butterfly Conservation, as Sir David Attenborough does now, in its 50th year, and was commissioned to paint a set of stamps for the Post Office that included the large blue, declared extinct in 1979, as an example of a ‘lost’ species. He would be delighted that the charity’s work has returned it to the Cotswolds.

His ability to forge friendships wasn’t confined to countrymen: upstairs in his cottage is an exquisite life drawing of the raconteur and dandy Quentin Crisp. ‘Whether duke or dustman, Gordon got on well with virtually everybody,’ wrote Mr Page.

The artist believed that town and country could exist in concert and was saddened by the rupture between the two. ‘He would be very disappointed by the arrogance of certain environmentalists and single-issue campaigners,’ believes Mr Page.

‘He considered that the people who worked on the land – shepherds, farmers, gamekeepers – were important, and should be listened to.’

It would be a fitting memorial to the great man if we could learn from his life, work and laughter – and heal the rifts that damage his beloved countryside.

To donate to the Gordon Beningfield Dorset Farm Appeal, telephone 01223 262999 or visit www.countrysiderestorationtrust.com

Beningfield’s best books

Here’s Octavia Pollock’s pick of the best Gordon Beningfield books to look out for if you’re new to the artist:

- Beningfield’s Butterflies (1978)

- Beningfield’s Countryside (1980)

- Hardy Country (1983)

- Beningfield’s English Farm (1988)

- Gordon Beningfield: The Artist and His Work (1994)

- Beningfield’s Vanishing Songbirds, (text by Betty Beningfield, 2001)

- Beningfield’s Orchards, (text by Betty Beningfield and Robin Page, 2004)

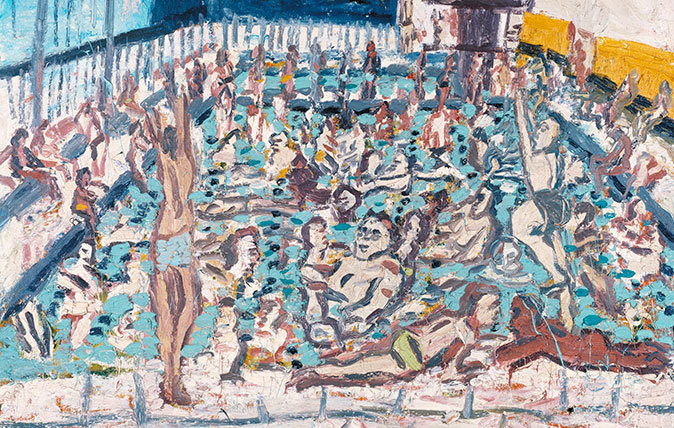

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

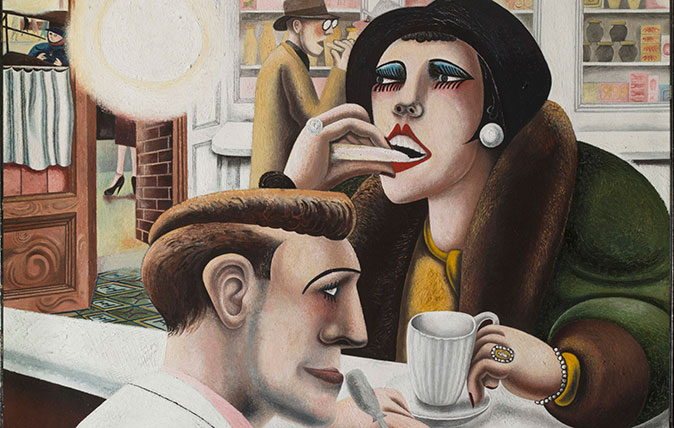

In Focus: The evocative, sensual masterpiece created in the wake of the First World War

Edward Burra was too young to have fought in the First World War, but his powerful oil painting The Snack

Credit: Getty

In Focus: The hand-drawn maps from which JRR Tolkien launched Middle-earth

'I wisely started with a map and made the story fit,' JRR Tolkien once wrote. A new exhibition in Oxford

In Focus: The ancient roman temple which lay under London, undiscovered for over 17 centuries.

The temple of Mithras has been beautifully restored by Bloomburg SPACE and now sits under their Headquarters by Bank tube

Octavia, Country Life's Chief Sub Editor, began her career aged six when she corrected the grammar on a fish-and-chip sign at a country fair. With a degree in History of Art and English from St Andrews University, she ventured to London with trepidation, but swiftly found her spiritual home at Country Life. She ran away to San Francisco in California in 2013, but returned in 2018 and has settled in West Sussex with her miniature poodle Tiffin. Octavia also writes for The Field and Horse & Hound and is never happier than on a horse behind hounds.