Giacometti at the National Portrait Gallery

Do not miss this new exhibition of Giacometti's work at the National Portrait Gallery this winter

On the face of it, 1964 looked set to be a bad year for Alberto Giacometti (1901–66). Diagnosed with cancer, the Swiss-Italian sculptor had to have part of his stomach removed; then, his mother, Annetta, the much-loved family matriarch, died at 92.

To any other artist, this double loss, fleshly and maternal, might have put paid to thoughts of work; to Giacometti, however, absence was the stuff of art. At some point in the middle of the year, he embarked on the ninth and last in a series of bronze portraits of his wife. Catalogued as Annette IX, it is now more widely known as Annette Without Arms.

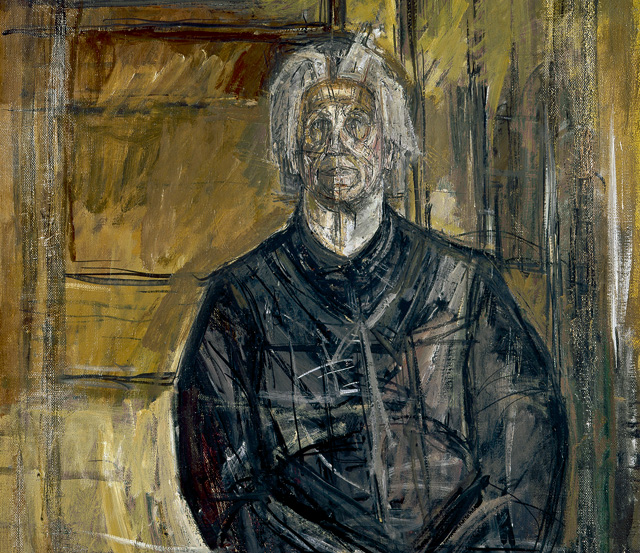

A visit to the National Portrait Gallery’s excellent show of Giacometti’s portraits, the first devoted solely to them, shows the sculpture’s name to be no more than the truth. Annette Giacometti, 22 years younger than her husband, looms towards us like the figurehead of a ship, her face an abstracted mass of forms and planes. Her lack of arms both draws our gaze and makes her vulnerable to it: Annette demands our attention, but also our compassion. Her maiden name, oddly, had been Arm. One wonders if her husband is playing on this, cutting her off from her background, making her entirely his. In Annette Without Arms, his own recent losses are made hers and vice versa. It is a portrait of extraordinary, unparalleled empathy.

All sculpture is made up of mass and void, what is there and what is not. Giacometti, however, is pre-eminently the sculptor of absence. Close your eyes and think of his work and you will almost certainly see skinny bronze figures, tall and etiolated, standing or striding along. Part of their power is their apparent anonymity, their sameness.

After the Second World War, after Hiroshima and Auschwitz, Giacometti’s stick figures seemed like new Everymen: the weight of the postwar world, manifest in the heavy emptiness about them, pressed on their thin shoulders. They were quickly claimed by the French Existentialists as fellow travellers in a godless universe; Jean-Paul Sartre, full of approval, saw Giacometti’s figures as ‘always halfway between nothingness and being’. That reading of them stuck. What this exhibition shows, however, is that it is by no means the whole story.

First, Giacometti’s sculptures did not spring fully formed from his imagination as hypotheses or symbols. If his mature period —the stick-man period, if you like—began in earnest in 1946, it was as a process of evolution rather than revolution. Pre-war works in this exhibition, such as Rita (about 1938), already show an urge to reduce and omit, a grasp of the eloquence of emptiness. Second, ‘Giacometti: Pure Presence’ makes it clear that the sculptor’s apparently anonymous figures actually had their roots firmly in portraiture and that portraiture, like charity, began at home.

Born into a family of artists, Giacometti made his first sculpture when he was 13: Portrait of Diego is a bronze bust of the younger brother who was to share his life and Paris studio until Alberto’s early death in 1966. (Diego Giacometti, also an artist, would survive him by 20 years.)

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

To love was to sculpt: Giacometti saw early on that accuracy was not the same thing as detail. His delightful bronze, The Artist’s Father (1927), reduces its subject to the child’s drawing of a head, with features etched on the flattened face as if squiggled on paper with a pen.

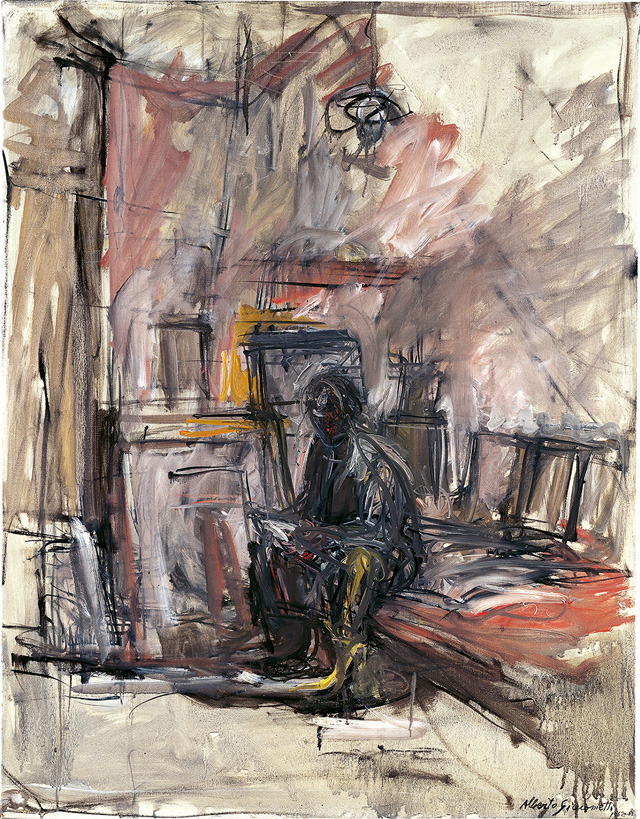

It is a telling moment. A third and important contribution of this show to our understanding of Giacometti is to place his bronze portraits alongside his paintings. If there is only one trademark stick figure in it— Woman of Venice VIII (1956) —there are as many works on canvas as there are in bronze.

These are not always as successful; the shrunken head of Diego in a Sweater (1953) is deeply moving, but that of Portrait of G. David Thompson (1957) has the faint air of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. At their best, however, Giaometti’s paintings are heartstopping; Man Seated on the Divan while Reading the Newspaper (1952–3), a portrait of Diego in their studio, has the feel for space of a Leonardo. This really is a wonderful show. Don’t miss it.

‘Giacometti: Pure Presence’ is at the National Portrait Gallery, London WC2, until January 10, 2016 (www.npg. org.uk/giacometti; 020–7766 7344). A catalogue of the same name by Paul Moorhouse is published by the National Portrait Gallery (£29.95).

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life