George Stubbs (1724–1806): Hero of the turf

George Stubbs, born 300 years ago, found Nature superior to art and approached his pictures with the eye of an anatomy scholar, yet no contemporary could rival him in capturing the elegance and character of racehorses, dogs and even zebras, as Jack Watkins discovers.

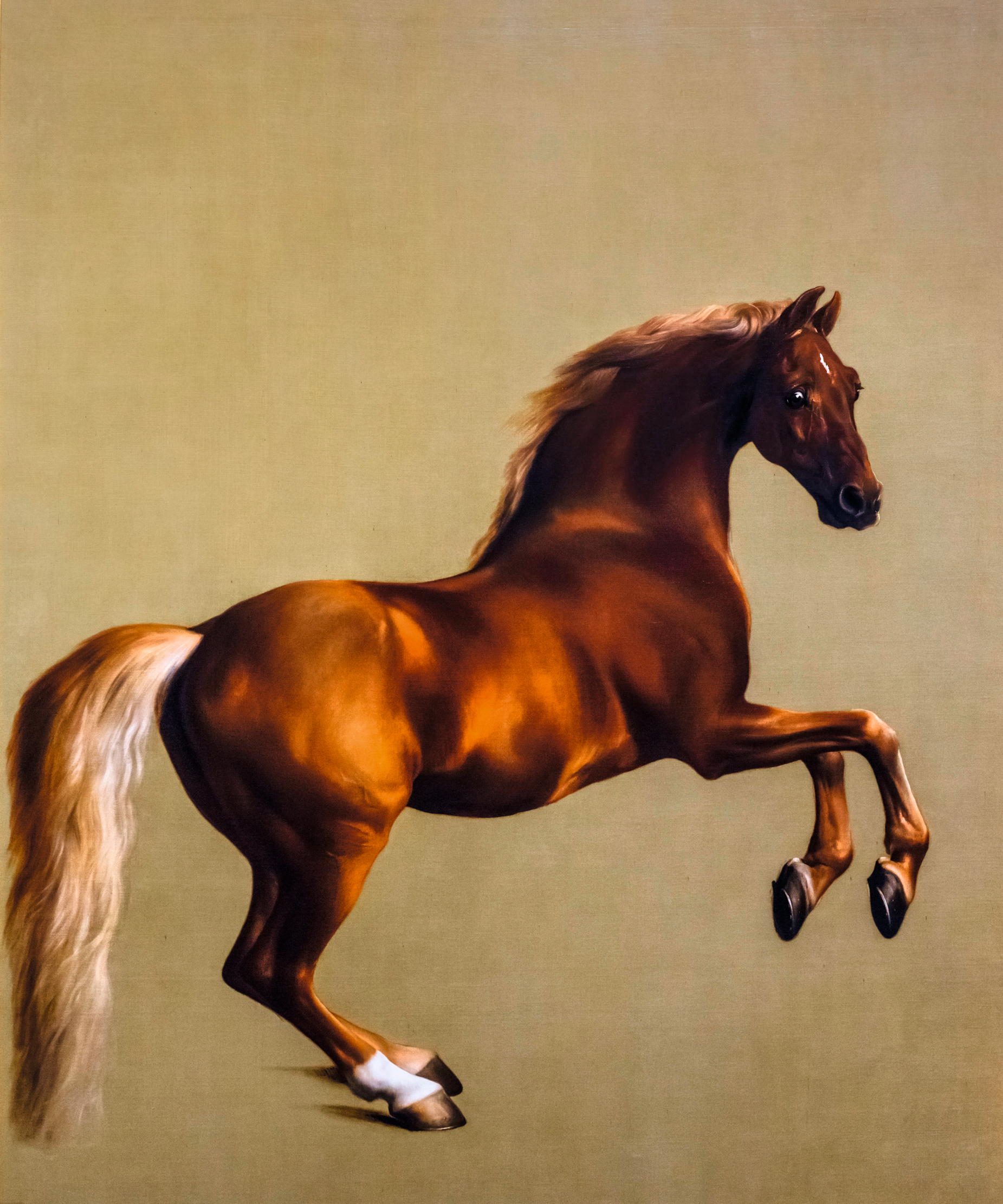

You could trace the history of the early years of the Turf through George Stubbs’s racehorse pictures. Marske, Eclipse, Gimcrack, Dungannon and Hambletonian were among the 18th-century champions he painted, sometimes set against the vast, austere backdrop of Newmarket Heath, the spiritual home of Flat racing. Ironically, however, Stubbs did not care for the crowds and noise of racetracks. His images were more reposeful and he seldom showed horses in their galloping strides. Perhaps it’s fitting that the animal in his most famous picture, Whistlejacket, was not even a great racehorse and was only moderately successful at stud.

Ever since the National Gallery acquired Stubbs’s rousing study of the 2nd Marquess of Rockingham’s prancing, flaxen-maned stallion in 1997, it has been one of the museum’s most popular paintings, a spellbinding portrait of grace, power and wildness. Yet only recently has Stubbs received adequate recognition. In his lifetime, he was disparagingly referred to as ‘Mr. Stubbs, horse painter’. After his death in 1806, with the finest works in private collections, he nearly disappeared from view. How could a man whose favoured subjects were racehorses be worth close scrutiny?

Vigorous advocacy by art historian Basil Taylor, the author of Stubbs (1971), eventually sparked a revival of interest and, by 2007, Judy Egerton’s description of the artist in her painstaking George Stubbs, Painter (2007) as ‘one of the greatest of British 18th-century painters, with a deep and unaffected sympathy for country life and the English countryside’ could hardly be disputed. It’s surprising that the 300th anniversary of his birth is not to be marked by a national exhibition.

Stubbs’s singularity was evident from an early age. The Liverpool-born son of a currier, he disappointed his father by spurning the thriving family business and announcing an intention to paint. A spell as assistant to local artist Hamlet Winstanley ended abruptly when, during an assignment at nearby Knowsley Hall, Stubbs walked out over the choice of which art works to reproduce. Copying Old Masters never held appeal for him. In his own words: ‘Nature was and is always superior to art.’

A horse of another colour: the life and times of George Stubbs

- August 25, 1724 Born in Liverpool

- 1754 Visits Rome. He is more interested in Lion & Horse, an ancient sculpture that was rescued from the Tiber in the 14th century, than in Old Masters

- 1762 Paints Whistlejacket

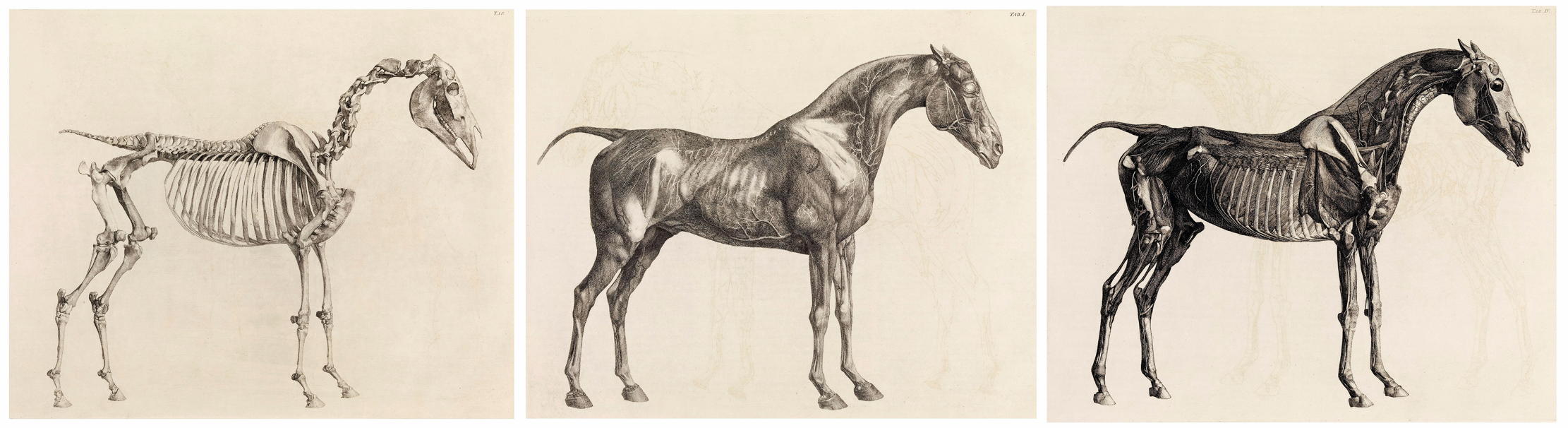

- 1766 Publishes The Anatomy of a Horse, the first work to advance understanding of its subject since Carlo Ruini’s Anatomia del Cavallo (1598)

- 1772 He completes The Kongouro from New Holland, from a kangaroo skin brought from Australia by Joseph Banks, together with Dingo

- 1773 Elected president of the Society of Artists

- 1790 Collaborates with son and engraver George Townley Stubbs to do a series of racehorse portraits for unsuccessful Turf Review project

- 1801 Takes Sir Henry Vane-Tempest to court over non-payment for his Hambletonian picture

- July 10, 1806 Dies suddenly. Buried in St Marylebone Church, London NW1, streets from the house he’d lived in since 1764. According to diarist Joseph Farington, ‘It is thought he was but in indifferent circumstances’

He studied human anatomy at York County Hospital, taught medical students and illustrated a book on obstetrics. Details of those early years are few, but, in 1756, he rented a farmhouse and barn on the Horkstow Hall estate near Hull, spending months dissecting horse carcasses, cutting the muscle layers down to the skeleton. He also made drawings of horses in natural poses, achieved by suspending the carcasses from a series of iron hooks and pulleys.

Although inability to find a suitable engraver meant that the resultant book, The Anatomy of a Horse, was not published until 1766 (typically, Stubbs learnt the requisite engraving techniques and did them himself), his arrival in London at the end of the 1750s, armed with his portfolio, gave him a point of introduction to wealthy aristocrats who, as he put it, ‘delight in horses, and who either breed or keep a considerable number of them’.

The first notable to commission Stubbs was Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, a horse and dog lover also fascinated by anatomy. In about 1759–60, Stubbs was invited to the Duke’s Goodwood estate in West Sussex. He spent nine months on three Downland sporting scenes, one of which showed the Duke with the celebrated Charlton Hunt. The most accomplished, however, featured the Duke’s recently acquired racehorses at exercise, playfully pursued by his pet dogs and watched by Mary, Duchess of Richmond, riding side-saddle.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Duke had recently commissioned William Chambers to design a large neo-Classical stable block for his array of racehorses, hunters, hacks and workhorses and it’s easy to imagine Stubbs hovering with a sketchbook, closely observing the grooms and stable lads, to whom he rarely neglected to give a stamp of individual character when he included them in his compositions.

Over the next few years, members of the gentry and other successful Turf patrons commissioned Stubbs, recognising an ability to produce accurate likenesses of their Thoroughbreds far in advance of the stiff, spindly legged, human-eyed depictions of earlier sporting artists, such as John Wootton and James Seymour. Stubbs’s painting of Lord Viscount Spencer’s handsome stallion Romulus (1761) was the first he ever exhibited. Lustre, held by a groom (about 1762) was among several pieces for Frederick, 2nd Viscount Bolingbroke. Richard Grosvenor, 1st Earl Grosvenor, also commissioned Stubbs to paint his racehorses (notably Bandy, in about 1763), but it was a hunting scene that proved outstanding. The Grosvenor Hunt (1762), set in the Cheshire countryside around the Earl’s Eaton Hall estate, was well composed and conveyed a terrific sense of movement. Water droplets thrown up as driven hounds splashed across a stream were detailed with the precision of fast-speed film.

Charles Watson-Wentworth, the 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, future prime minister and one of the great racing aristocrats (remembered in the Rockingham Stakes run at York every October), was perhaps Stubbs’s most appreciative patron. At Wentworth Woodhouse in South Yorkshire, the Marquess accumulated a vast collection of ancient and modern sculpture and three studies Stubbs produced for him were set against unfigured backgrounds. Many contemporaries thought the pieces looked unfinished, but Rockingham valued the frieze-like quality of Whistlejacket on its 10ft canvas, Whistlejacket with head groom Mr Cobb and 2 Other Stallions and the exquisitely arranged Mares and Foals.

Other patrons also expressed an interest in paintings of their broodmares, so Stubbs produced several variations on Mares and Foals for them, a type of painting for which there was little precedent, certainly in England. The settings included trees, woods, streams or lakes and even a mountain, offering glimpses of Stubbs’s eye for landscapes. These pictures also reflected a contrasting side to the racing aristocrats’ quest for victory on the track, namely their long-term dedication to the development of Thoroughbred bloodlines, a painstaking endeavour pursued by several owner-breeders to this day.

However, Stubbs also let his imagination go wild with a series of melodramatic lion and horse pictures. The Creswell Crags backdrops against which they were often set were so accurate that some of the rock formations have been identified. Among his human portraits, one of the Marquess of Rockingham’s long-serving retainers, Thomas Smith at the age of 70 (1755–56) is particularly sympathetic. Unsentimental depictions of farm workers, such as Reapers (1783) and Haymakers (1785), are another oft-overlooked aspect of his oeuvre.

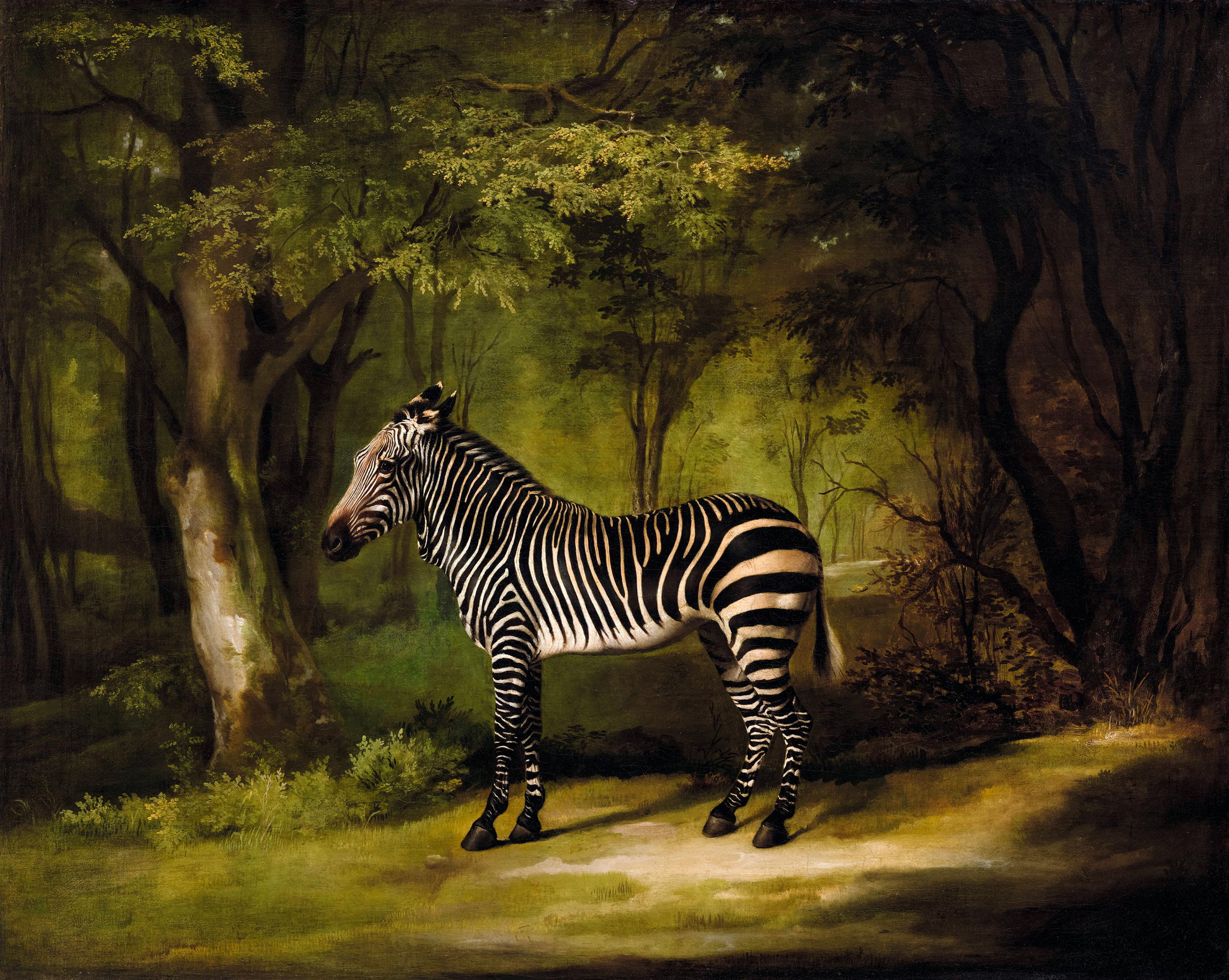

Yet animals were his abiding inspiration. There were some delightful paintings of dogs in outdoor settings — Egerton considered Ringwood, a Brocklesby Foxhound (1792) a picture most ‘truthful to the living, sentient nature of any animal ever portrayed in England’. Exotic beasts were another obsession for Stubbs, often painted or drawn for his own curiosity. He depicted a Bengal tiger, a rhino and a yak, but most endearing was the first zebra to arrive in England, kept in Queen Charlotte’s menagerie at St James’s Park. Described in The London Magazine as ‘one of the most inoffensive animals in the world’, it mesmerised everyone with its black-and-white stripes and ‘loud and harsh braying’ — including Stubbs, who painted it in 1763.

Stubbs fell from fashion in his lifetime, but money was never his prime motivation and he beavered away to the end. One of his last works was arguably his finest. Hambletonian had won the St Leger at Doncaster in 1795, but Stubbs’s 1799 painting pictured Sir Henry Vane-Tempest’s great Northern racehorse with a baleful-looking trainer and boyish lad, after a gruelling race at Newmarket from which he never recovered. As well as his brute power, Stubbs captured the horse’s panting, post-race exhaustion. Hambletonian, Rubbing Down is a study of the bravery of a racehorse in pursuit of glory that has never been surpassed.

Picture credits: Alamy; Bridgeman Images; Christie’s/Bridgeman Images

Credit: Two Hacks by George Stubbs (Parker Gallery)

Long-neglected ‘copy’ turns out to be original Stubbs worth £750,000

Gallery owner Archie Parker thought something was amiss when he came across this painting in an online sale catalogue, and

The Titian masterpiece found in a plastic bag at a London bus stop has sold for £17.6 million

The painting that secured Titian’s reputation as 'the greatest painter of the Venetian Renaissance' is going up for sale, 30

In Focus: Alfred Munnings, the straight-talking, self-promoting artist who preached that art was 'to fill a man’s soul with admiration and sheer joy'

Pictures should ‘fill a man’s soul with admiration and sheer joy’, Sir Alfred Munnings famously said. Octavia Pollock charts his

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill