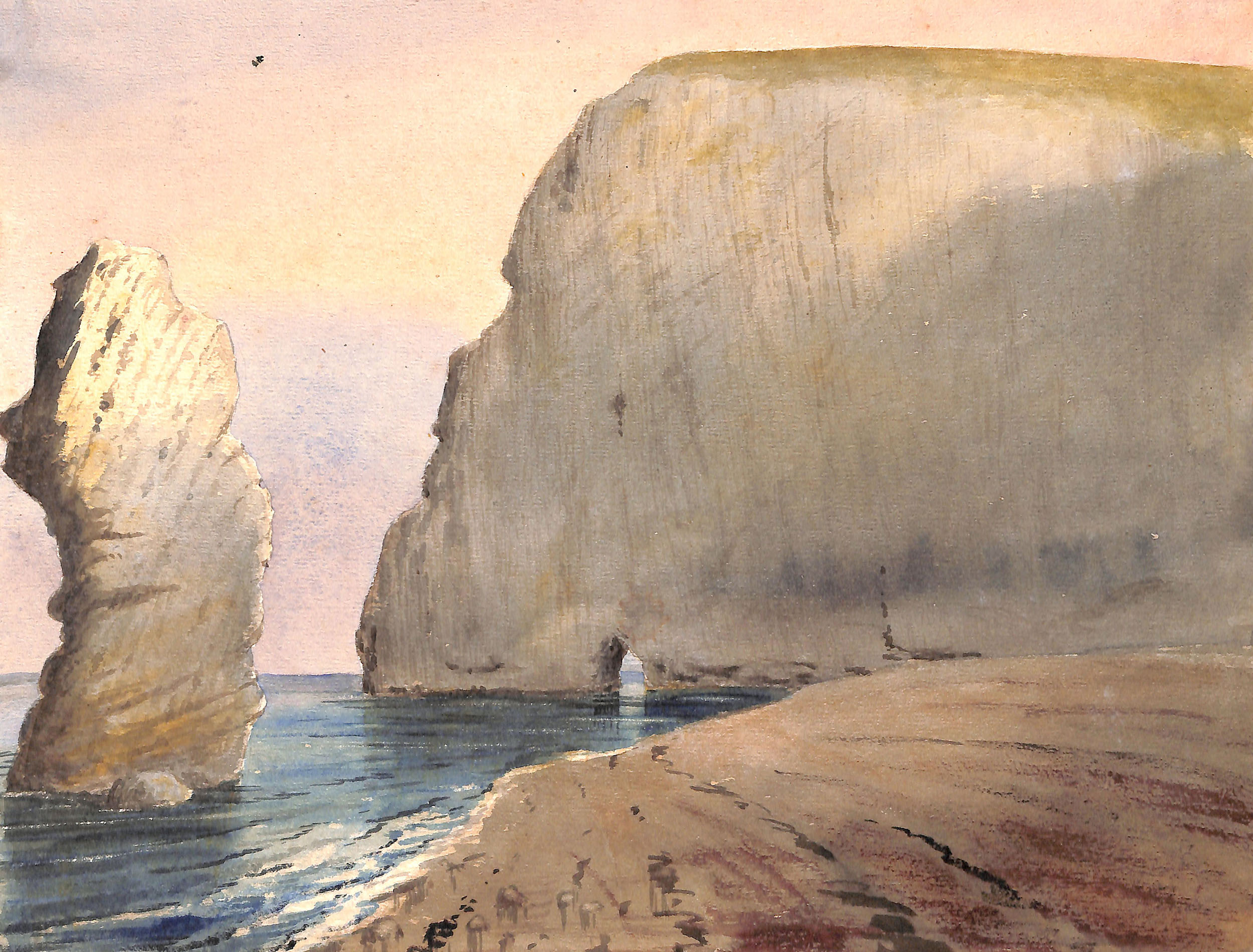

In Focus: The vast trove of watercolours documenting the world as it looked before photography

The explosion in watercolour painting in the 18th century came not from artists' studios but rather from the unbeatable practicality of this medium prior to the birth of portable cameras. Mary Miers explains how these pictures are now being put to use once more.

Today, we think of watercolour as a branch of painting. Yet it wasn’t always this way: there was a time when this particular discipline was a matter of practical necessity rather than one of self-expression.

The skill of the medium developed not in artists’ studios but rather in the hands of soldiers and surveyors, scientists and antiquaries, travellers and spies, who used watercolour draughtsmanship to document their exploration. Canvas and oils weren’t always available, but paper and paints were much easier to rely upon. The 1750s heralded a golden age, when the availability of good paper and portable blocks of paint saw artists – notably the English – excel at watercolour.

The result is that thousands of watercolours were painted of places, plants and events as they were recorded in watercolour, long before black-and-white photography took over as the principal means of visual documentation.

For many years these have pictures have been largely overlooked, but now a new project has realised the great value they hold for seeing the world as it was 250 years ago – contributing, for example, to a recent survey of British coastal erosion.

This ambitious new initiative comes in the form of a free website www.watercolourworld.org – that allows us to navigate the world as it appeared between 1750 and 1900 has been launched. Already, more than 80,000 geotagged images can be accessed by zooming in on a map or searching by subject, artist, date or place.

The scale of this online archive is potentially vast, as there are untold numbers of watercolours in public and private collections globally, the majority uncatalogued and too fragile to display. Now, they can be digitised and their colourful detail rediscovered and preserved.

‘With the world at risk from climate change, rising sea levels and worse, the project will provide scientists and environmentalists with an accurate visual account of much of the natural world as it used to be,’ explains Watercolour World founder Fred Hohler.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘And to conservationists and historians, it will provide the evidence to conserve and rebuild structures, to find lost places and to see the roots of human progress.’

See www.watercolourworld.org for more information

Constable ‘added rainbow after his masterpiece first went on display’

In Focus: The paintings which show Monet's genius for architecture as well as nature

Think of Monet and you think of reflections and nature, but his works included huge amounts of architecture and other

Six glorious paintings which perfectly encapsulate the art of the conversation piece

Matthew Dennison celebrates the conversation piece, the intimate Georgian form of portraiture which celebrated families without the usual swagger or

The incredible tale of the foxglove, from curing to disease to inspiring Van Gogh’s most striking paintings

A tale of skulduggery, poisoning, witches and even marketing men runs through the history of the foxglove, as Ian Morton

Mary Miers is a hugely experienced writer on art and architecture, and a former Fine Arts Editor of Country Life. Mary joined the team after running Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. She lived in 15 different homes across several countries while she was growing up, and for a while commuted to London from Scotland each week. She is also the author of seven books.

-

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'

Minette Batters: 'It would be wrong to turn my back on the farming sector in its hour of need'Minette Batters explains why she's taken a job at Defra, and bemoans the closure of the Sustainable Farming Incentive.

By Minette Batters Published

-

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the world

'This wild stretch of Chilean wasteland gives you what other National Parks cannot — a confounding sense of loneliness': One writer's odyssey to the end of the worldWhere else on Earth can you find more than 752,000 acres of splendid isolation? Words and pictures by Luke Abrahams.

By Luke Abrahams Published