In Focus: The unforgettable art of the British WW1 soldier who might have been the Kaiser's son

Karl Hagedorn's contribution to Post-Impressionist art in Britain has been neglected for too long – a new exhibition in Chichester seeks to right that wrong and put this intriguing figure back on the map. Lilias Wigan reports.

In December 1910, the painter-critic Roger Fry shook the London art world when he launched the exhibition Manet and the Post Impressionists, at The Grafton Galleries. Cited as ‘the Art-Quake of 1910’, it was lampooned by London critics and proved a disastrous blow for his career.

Fry had introduced the London public to the work of the late Post-Impressionist artists such as Cézanne, Gaugin, Seurat and Van Gogh, and they found it scandalous. Not only did the pictures lack accurate representation, they prioritised form over content – often with distorted and simplified shapes and patterns that both challenged and insulted the conventional British aesthetic. In her essay Bennett and Mrs Brown, Virginia Brown wrote ‘On or about December 1910 (…) human character changed.’

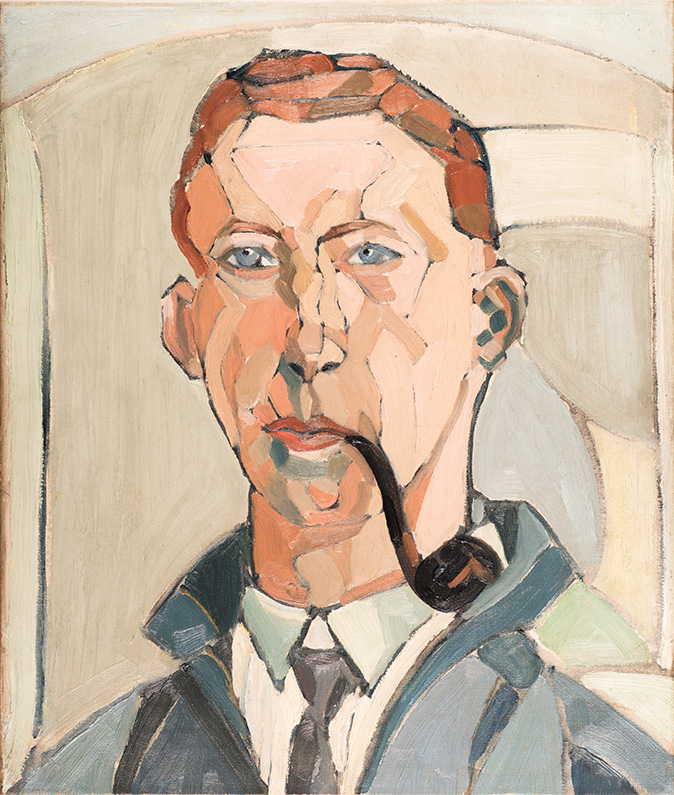

It was within this context that one of the earliest Post-Impressionists in Britain, Karl Hagedorn (b. 1889), was working in Manchester. He studied at the Manchester School of Art under the French Impressionist painter Pierre Adolphe Valette and then at the Slade School of Fine Art in London.

Although born in Berlin, Hagedorn emigrated to England in 1905 at the age of 16 and travelled extensively across Europe throughout his career. Circumstances were uneasy for a German living in wartime Britain – for Hagedorn in particular, as he was thought to be the illegitimate son of Kaiser Wilhelm II – but, undeterred, he volunteered for the British Army, where he served from 1914-19.

With the rise of photography, Hagedorn no longer felt the need for art to be so representational; instead, he sought inspiration from artists on the continent. A pivotal point in his career came when, on moving to Paris to work in the studio of Maurice Denis in 1912, he met his artist-hero, Henri Matisse. Hagedorn idolised him – he even kept a cigarette given to him by Matisse as a souvenir for the rest of his life, an act which embodied the profound impact that Matisse had on his work.

‘Globular, yellow lollipop trees stand like troops as the sun beats down onto the houses, illuminating them with a stark brightness’

Modern British art history has struggled to place Hagedorn, mainly because of ignorance of the Post-Impressionist style at the time, and there has been little recognition of his significance since. But now the Pallant House Gallery, in partnership with Liss Llewellyn Fine Art, has staged their first exhibition devoted to the artist’s work.

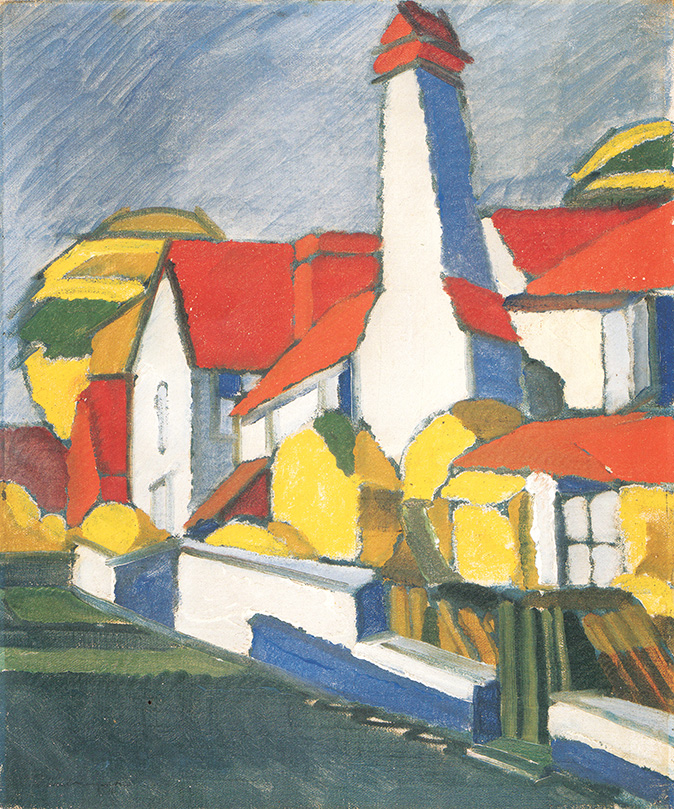

The painting Village Street was made in 1916, the year that the artist’s only child was born (tragically, she died aged twelve). It was also the year of his first exhibition at the Society of Modern Painters, Manchester, to which he became secretary.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Hagedorn’s palette of contrasting primary colours and angular forms exemplifies his bold innovation and the very ‘un-British’ influences that alienated his work from British art history. Though devoid of people, the village scene is animated. Globular, yellow lollipop trees stand like troops as the sun beats down onto the houses, illuminating them with a stark brightness.

The mottled brush marks and bold outlining suggest the Pointillist influence of European contemporaries. The strangeness of the jarring shapes, termed ‘cubist puzzles,’ left the critics baffled and lead to comparisons with the ‘barbarous’ and ‘wild’ Fauves.

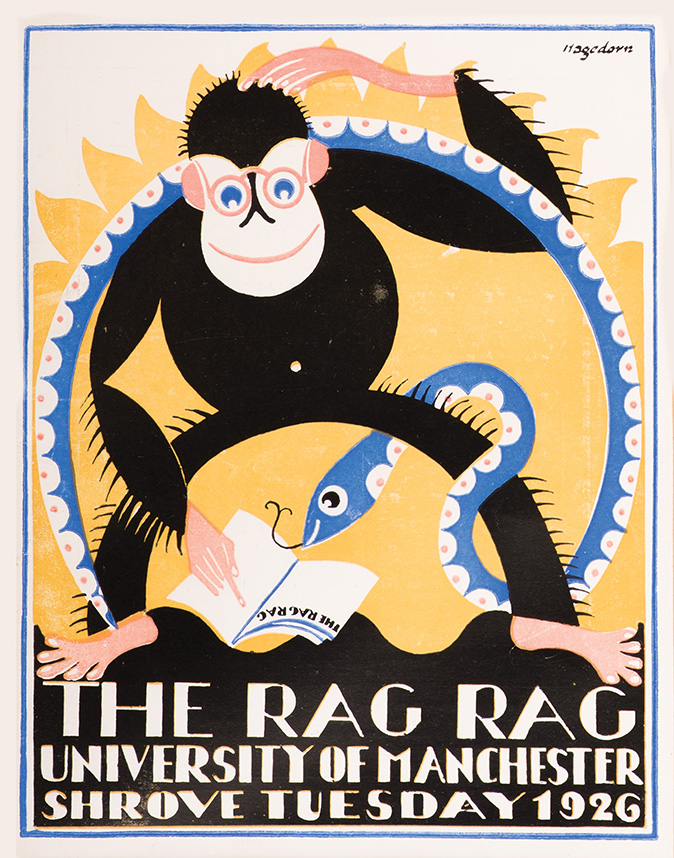

Hagedorn’s ‘rhythmical expressions in line and colour’, as he described them, are among the earliest examples of Post-Impressionism in Britain. His oeuvre widened to include commercial designs for posters advertising washing powder, Margarine or simply to ‘Buy British’, as well as Manchester University’s ‘Rag mag’ covers.

However, by the 1920s, in keeping with the ‘return to order’ that characterised much of the art produced in the wake of the First World War, his landscape painting had retreated from its earlier more radical Modernism.

The exhibition Karl Hagedorn: Rythmical Expressions illuminates the role that this overlooked artist played in introducing Britain to a radical European style that would play such an important part in the development of Cubism, Art Nouveau and German Expressionism.

‘Karl Hagedorn: Rythmical Expressions’ is on view at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, until Sunday 3 February 2019. See pallant.org.uk/whats-on/karl-hagedorn-rhythmical-expressions for tickets and further information.

Credit: Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973): <i>Girl Before a Mirror </i>(Boisgeloup, March 1932). New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

In Focus: The Picasso portrait which revealed to the world his 22-year-old muse

The Tate Modern's first-ever exhibition focusing solely on Picasso concentrates solely on a single year in the life of this

Credit: David Milne, Tent in Temagami, 1929, Collection of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario, bequest from the Douglas M. Duncan Collection, 1970. © The Estate of David Milne

In Focus: The Canadian hermit's work that is a dystopian alternative to Monet

Canadian artist David Milne moved from city to country, eventually ending up as a hermit in a remote part of

In Focus: The ancient roman temple which lay under London, undiscovered for over 17 centuries.

The temple of Mithras has been beautifully restored by Bloomburg SPACE and now sits under their Headquarters by Bank tube

In Focus: The gleaming cups made from gold and kingfisher feathers at the heart of a great British collection

When Richard Wallace, the illegitimate son of a Marquess unexpectedly inherited his father's art collection, he did himself and his

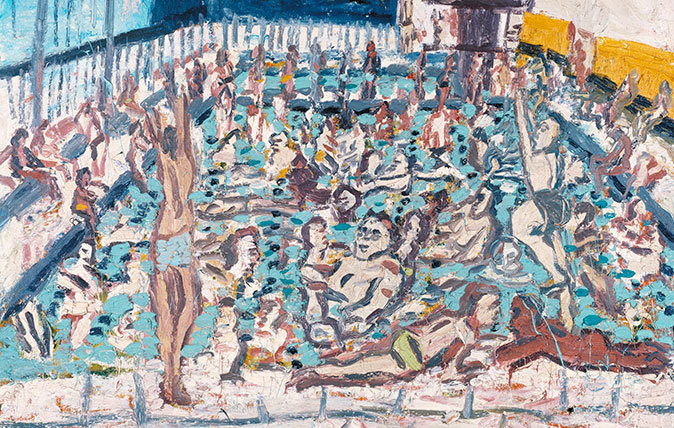

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

-

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabinQatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin has been setting the standard for Business Class travel since it was introduced in 2017.

By Rosie Paterson

-

Six of the best Clematis montanas that every garden needs

Six of the best Clematis montanas that every garden needsClematis montana is easy to grow and look after, and is considered by some to be 'the most graceful and floriferous of all'.

By Charles Quest-Ritson