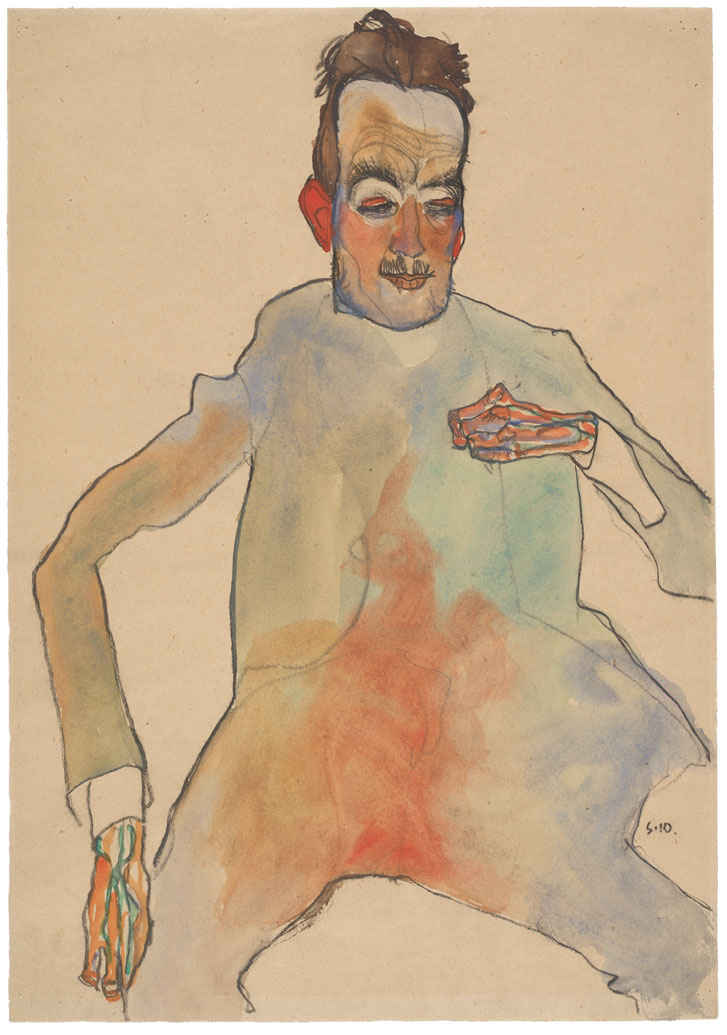

In Focus: A silent cellist, blazing with pleasure, by Klimt's great young protégé Schiele

When he first came on to the Vienna art scene, Egon Schiele hero-worshipped Gustav Klimt. Once they met the two became friends, forming a bond and inspiring each other's work, as Lilias Wigan explains.

1918 saw the signing of the Armistice ending the First World War, and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It also coincided with the death of two of the Empire’s most distinguished artists, Gustav Klimt (b.1862) and Egon Schiele (b.1890). To mark the centenary of their demise, the Royal Academy has collaborated with the Albertina Museum in Vienna to explore, through an exhibition of their works on paper, the artistic relationship between the two artists and the extent to which they influenced and supported one another. The show offers a rare opportunity to see these works; they're so fragile that they are rarely available on public display.

When Schiele enrolled at the acclaimed Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna as its youngest student, Klimt was already well established in the European art world. He was already receiving prestigious commissions and thinking against the canon of conventional aesthetic taste. In 1897, he founded a progressive artists' co-operative called the ‘Seccession’, with which Schiele would later exhibit.

He proved a seminal influence on the budding young artist, evident in the first rooms of the exhibition, where we see Schiele’s early devotion to embellished patterns – a distinguishing characteristic of Klimt’s work from Japanese art. Schiele even drew on packing paper and experimented with square formats, both approaches favoured by Klimt.

'Where Klimt’s drawings are principally studies for paintings, Schiele’s are autonomous works of art bearing his signature'

Strangely, it was not until 1910 that the two artists met, although Schiele had already undergone his most fanatical disciple-like phase by this point, describing Klimt as ‘a human being of rare depth’.

'I went through Klimt until March. Now I think I am entirely different,' he recalled. From then on, he evolved an anxious, starkly immediate and often erotic style independent of his idol. One poignant example is the picture on this page, a mysterious crayon and watercolour from 1910 entitled The Cellist.

Here, Schiele describes by elimination, relying on the viewer’s imagination to see what is merely implied. Whether or not he titled the work (it’s unlikely he did), the subject matter is enigmatic and sensual. The player’s arms cradle an invisible instrument, his skeletal fingers pressing on absent strings. Between his bowed legs wrapped around the missing object, Schiele exposes a large void of watercolour wash.

A swathe of red rises like smoke through the groin and is soaked up by the performer’s florid cheeks, where it spreads to crimson ears. The ears seem to blaze with pleasure from the melody of the supposed cello.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Schiele adopted a similar burning red tone for details in some of his other portraits; lips, labia and nipples of young prostitutes glow vermilion. In The Cellist, however, where the face and hands are worked into with dense crayon markings, the body is an inscrutable, vague mass of suffused pigment. Like much of Schiele’s themed work, the picture is ambiguous and highly provocative.

Klimt tended to use bold contouring with little or no attention to shading. Many of his female portraits favour the archetypal femme fatale, as opposed to Schiele’s unflattering depictions of gaunt figures and angular bodies. Schiele prioritised the visceral over the formal, character over representation. The strength of his work lies in the uncomfortable; the instinctive honesty; the vulnerable yet provocative nature of the subjects. Where Klimt’s drawings are principally studies for paintings, Schiele’s are autonomous works of art bearing his signature.

When Klimt died of pneumonia in February 1918, Schiele made three drawings of his mentor at the morgue. Just a few months later he succumbed to flu himself, dying at the age of just 28.

Klimt / Schiele: Drawings from the Albertina Museum, Vienna runs until 3rd February 2019 in the Sackler Wing of Galleries, Burlington House, Royal Academy of Arts, London. Tickets are available from www.royalacademy.org.uk.

Vienna: The mini-break that oozes old-time glamour

Jane Watkins explores the Austrian capital that marks the 150th anniversary of Ringstrasse this year.

Sotheby’s set new London auction record with £48m Klimt leading the way

A sale of Impressionist, Modern and Surrealist paintings at Sotheby's on Wednesday night set the record for an auction staged

Credit: Justin Paget

Upmeads: A Modernist castle as odd and beguiling today as ever

Boldly conceived by a leading shoe manufacturer and his wife in 1908, this house, recently restored, elicited much comment, as

My favourite painting: Richard Calvocoressi

'Its swirling movement, rich colour and dramatic light effects recall Baroque painting'

Credit: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas - The Burrell Collection, Glasgow © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

In Focus: The Degas painting full of life, movement and 'orgies of colour'

Lilias Wigan takes a closer look at one of the key work's at the Degas exhibition at the National Gallery

Credit: Michael Armitage, The Flaying of Marsyas, 2017. © Michael Armitage. Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby). Courtesy of the Artist and White Cube.

In Focus: Michael Armitage's image of African violence that points the finger back at the western world

Michael Armitage's The Flaying of Marsyas is the centrepiece of his exhibition in South London. Lilias Wigan examines it in