In Focus: Ruskin, Turner and the ‘prophetic warning of impending environmental catastrophe’

Simon Poë is blown away by ‘Ruskin, Turner & the Storm Cloud’ at the Abbott Hall Art Gallery in Kendal, an exhibition about climate change and mental health, plus the pleasures and pains that come with seeing clearly.

What is happening to the weather? What is climate change doing to the planet? These are urgent questions, much in the news, that are addressed by this timely exhibition. There is a full supporting cast, for context, but the three stars of the show are J. M. W. Turner, John Ruskin — better known as a writer, but also a talented painter in watercolour — and contemporary artist Emma Stibbon. The work is beautiful, but the message is stark.

This year sees the 200th anniversary of Ruskin’s birth, but this exhibition is no mere celebration. It takes its title from that of a lecture, ‘The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century’ — given by Ruskin at the London Institution in February 1884 and published later that year — which has long been dismissed as one of his late, ‘mad’ books, but which is now coming to be recognised as a prophetic warning of impending environmental catastrophe.

The exhibition reaches a climax with recent depictions of Swiss mountains, done on huge sheets of paper in Indian ink, but it starts quietly, with a small volume of poetry. On February 8, 1832, Ruskin was given Italy by Samuel Rogers for his 13th birthday. This was a momentous gift, because it was where he first saw the work of Turner. A copy of Italy, open at one of the tiny vignettes with which it is illustrated, is among the first exhibits in the show.

Ruskin’s own first book, Modern Painters — part one of a work that would eventually stretch to five volumes — came out in 1843. It began as a vindication of Turner’s controversial late paintings — his sanity, too, was called into question towards the end of his career — but it spiralled out from there to discuss all sorts of other things. Three of its chapters are devoted to ‘the truth of clouds’.

There were no illustrations. Instead, the author referred his readers to Turner’s pictures in Italy, so highly did he regard their meteorological accuracy and the quality of the engravings.

Ruskin loved Nature’s beauty and spent a lot of time gazing at the sky. He also loved art, but tended to admire it most when it rendered natural beauty with scrupulous truth. Turner’s work remained a touchstone for him until the end of his life.

It was an unhappy life, despite its wealth and privilege. His problems probably had their roots in his childhood, which was both indulged and deprived, but they came to a crisis when he experienced a terrifying mental breakdown one night in 1878 at Brantwood, his Lake District house.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In ‘The Storm-Cloud’, he claimed he was grateful ‘that my mind is capable of imaginative vision, and liable to the noble dangers of delusion’. Certainly, despite his occasional bouts of mania, Ruskin’s perception, particularly of natural phenomena, remained clear, but the unremitting clarity of his vision may have been one of the things that sometimes made life almost unbearable.

It seemed to him that the world — literally and metaphorically — was getting darker and dirtier and that few people were paying attention. He showed the audience one of his paintings, of ‘an old-fashioned sunset — the sort of thing Turner and I used to have to look at — (nobody else ever would) constantly. Every sunset and every dawn, in fine weather, had something of the sort to show us. This is one of the last pure sunsets I ever saw, about... 1876’.

Ruskin’s sense was based on a lifetime of looking — on an artist’s impression, rather than on scientific data — but he was right. Emma Stibbon was asked to revisit some of the scenes painted and photographed by both artists. The resulting pictures, together with some of Turner’s paintings, bookend the ‘Sublime’ tradition in British painting, according to which art achieves beauty partly by inspiring feelings of terror.

In The Passage of Mount St Gotthard, Taken from the Centre of Teufels Broch (Devil’s Bridge) (1804), for instance, Turner evokes the vertiginous horror of the crossing, which people often did on hands and knees.

The new paintings are awe-inspiring in the best sense of the word, but they also confront us with the awful possibility that, within our lifetimes, the glaciers will be gone and the mountains no longer snow-capped — and we have every reason to be afraid.

‘Ruskin, Turner & the Storm Cloud’ is at Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, Cumbria, until October 5 — www.abbothall.org.uk. A book of the same title by Suzanne Fagence Cooper and Richard Johns is out now (Paul Holberton Publishing, £20).

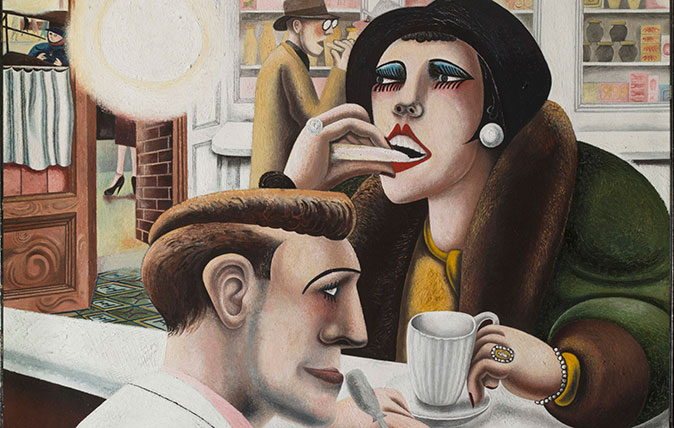

In Focus: The evocative, sensual masterpiece created in the wake of the First World War

Edward Burra was too young to have fought in the First World War, but his powerful oil painting The Snack

Credit: David Milne, Tent in Temagami, 1929, Collection of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario, bequest from the Douglas M. Duncan Collection, 1970. © The Estate of David Milne

In Focus: The Canadian hermit's work that is a dystopian alternative to Monet

Canadian artist David Milne moved from city to country, eventually ending up as a hermit in a remote part of

In Focus: The war artist who taught Hockney, and whose reputation is only going to grow

In Focus: The Norman Ackroyd landscape etchings that have sparked comparisons with Turner

This week marks the last chance to see Norman Ackroyd's sublime exhibition in Richmond. Lilias Wigan urges you to take

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill