In Focus: Photography's first-ever selfie, as taken by one of Yorkshire's greatest ever inventors

A Yorkshire scientist by the name of Washington Teasdale took a picture which is generally thought to be the first 'selfie' in the history of photography. Toby Keel takes a closer look.

Ever since there has been art, there have been self-portraits. There are 30,000-year-old cave paintings in which the artist strove to do nothing more (or less) than record an image of their hand for posterity. But the art of the selfie really took off in the last half of a millennium, notably thanks to the influence of Albrecht Dürer, the 16th century superstar artist who created moody and intense images of himself throughout his career.

But why? What prompts an artist to make themselves their subject? Artists and thinkers have wrangled tirelessly with this question. Some, such as Francis Bacon, claim that it's a matter of unfortunate necessity, once saying that, 'I loathe my own face, and I've done self-portraits because I've had nobody else to do.'

Others have made grander claims. Andy Warhol used his as a way of improving upon reality ('Always omit the blemishes — they're not part of the good picture you want'), while Warhol's fellow American artist Scott Kahn thought it should be the opposite: 'Self-deceit is a most damaging trait. The remedy, for an artist, is to paint a self-portrait.'

The coming of the photographic age served to make self-portraiture easier, and the smartphone era has put that photographic studio into all of our pockets. It wasn't always the case, however. For the first few decades after its inception in the 1820s, getting a decent image was still a technical feat that involved far more perspiration than inspiration.

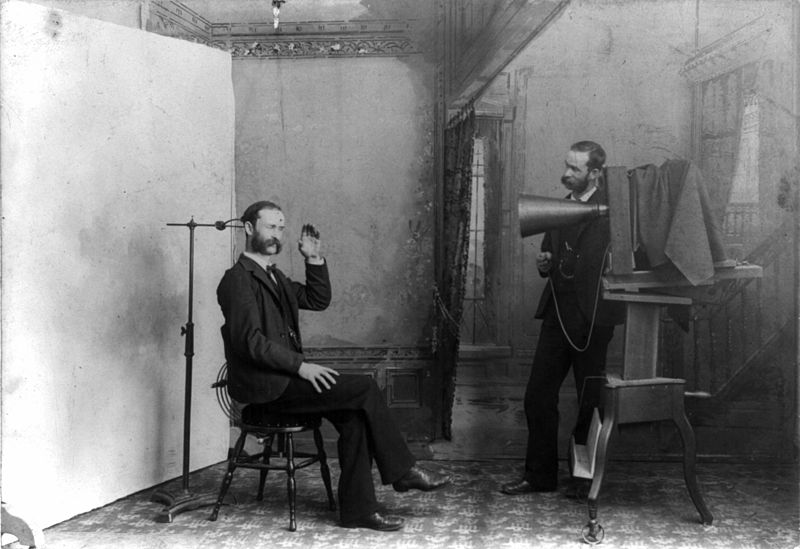

Technological advances changed that in the later years of the 19th century — so much so that in 1893 photographer A. H. Wheeler even produced this double self-portrait picture poking fun at how awkward it once was. The clamp at the back of his head, incidentally, is to stop it from moving during the exposure.

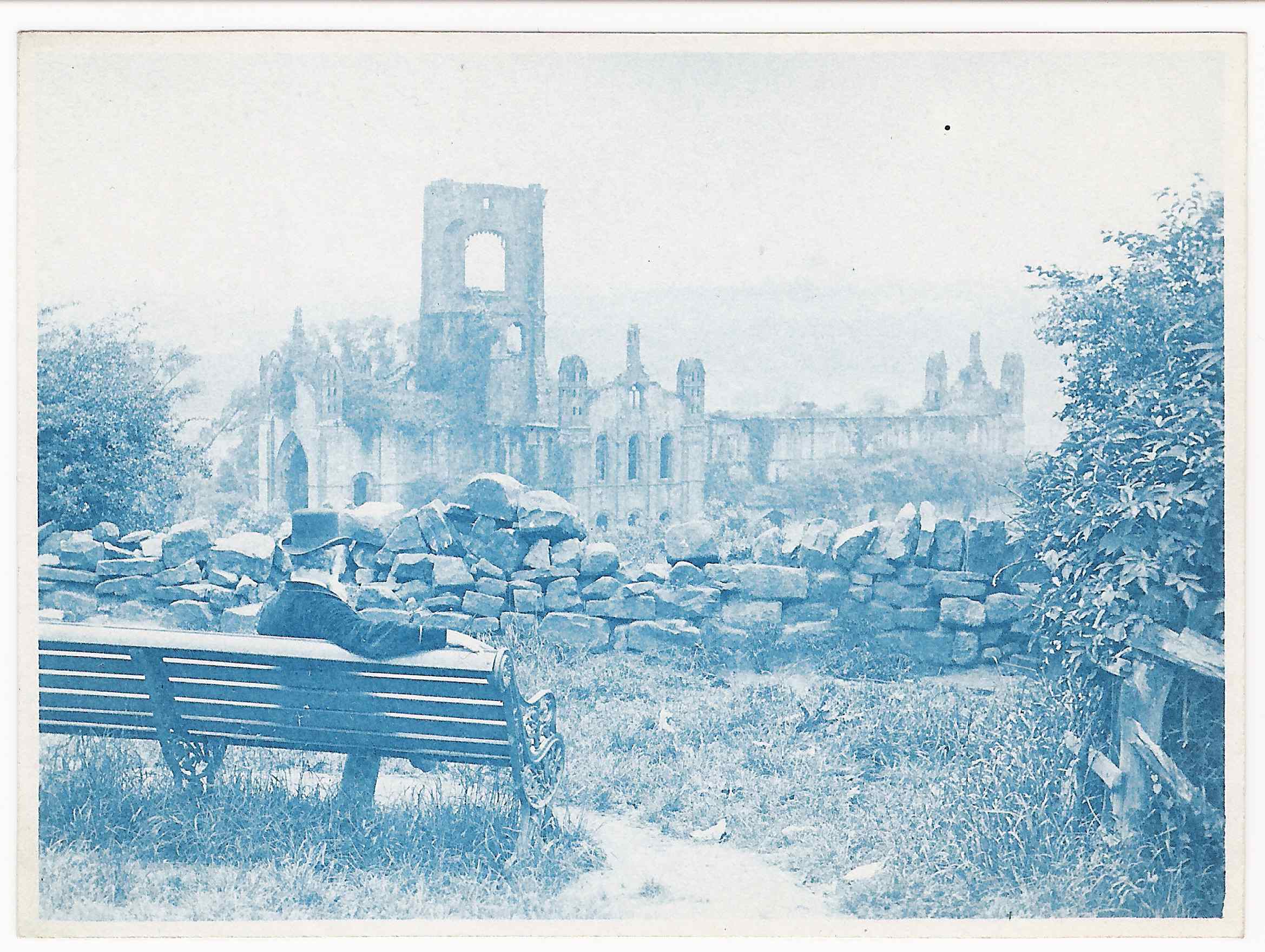

Wheeler's image wasn't the first photographic selfie, however. That honour belongs — so it's believed, at any rate — to a Yorkshireman with the wonderful name of Washington Teasdale, who created the picture you see at the top of this page in 1883.

Teasdale used a process called 'Cyanotype', the white-and-blue imagery technique used by architects to create blueprints — but the subject of the image wasn't quite the man himself. He was photographing the ruins of Kirkstall Abbey, a 12th century monastery in the north west of Leeds that was much beloved of the romantic artists of the time — JMW Turner was among those who came to Leeds to paint it.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Teasdale's process involved him setting up his camera, then rushing around to the bench in front of the ruins and holding his pose for a quarter of an hour or so, before nipping back to the camera. The result is a beautiful, almost mystical image which takes this picture far beyond a view of the Abbey, telling us perhaps more about Teasdale's love of this particular view than it does about the medieval ruin below.

The selfie wasn't his only innovation. Teasdale had a powerful and creative mind, and won acclaim for his pictures of the moon taken through a telescope and his invention of the field microscope — he was a keen entomologist.

This image feels like a counterpoint to all that. The world saw him as a scientist, but Teasdale's photograph highlights a romantic, whimsical aspect of his nature, a man revealing something about himself which perhaps other people did not see. In that sense, this self-portrait is absolutely at the heart of a great artistic tradition.

A huge reproduction of Teasdale's picture is on display at the Leeds Industrial Museum at the moment, as part of their 'Leeds to Innovation' exhibition, which runs right through until September 2021. Find out more at the museum's website.

In Focus: The wartime masterpieces of Alfred Munnings

Huon Mallalieu welcomes the opportunity to see a significant body of wartime paintings alongside other works by Munnings in his

In Focus: A silent cellist, blazing with pleasure, by Klimt's great young protégé Schiele

When he first came on to the Vienna art scene, Egon Schiele hero-worshipped Gustav Klimt. Once they met the two

In Focus: The Van Dyck portrait that shows Charles I as monarch, connoisseur and proud father

Lilias Wigan takes a detailed look at Van Dyck's Greate Peece, one of the highlights of the Royal Academy's stunning

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.