In Focus: The paintings which show Monet's genius for architecture as well as nature

Think of Monet and you think of reflections and nature, but his works included huge amounts of architecture and other elemtns of the modern, technological age in which he lived. Caroline Bulger takes a look at some of the key scenes in a new exhibition at the National Gallery celebrating these works.

No one thinks of Monet primarily as an architectural painter, but an astonishing number of his canvases include houses, churches, hotels, bridges and railway stations and they are never without significance. Churches help to identify villages; rustic dwellings can insert a human presence in an otherwise bleak landscape; urban apartment blocks and factories are beacons of modernity; and hamlets seen from afar can serve as pictorial punctuation points, the reds and greys of their roofs and walls standing out against the green hues of Nature.

A new exhibition at the National Gallery in London – ‘The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Monet & Architecture’ – does its best to remind us of this other string to the artist’s bow. There are over 75 pictures – more than a quarter of them from private collections – cutting a vertical slice through Monet’s long life, featuring canvases that he painted right from the very beginning of his career through to his last 15 years, when he stopped painting architecture altogether and devoted himself to his garden and the familiar watery reflections of his lily pond in Giverny.

Monet spent his childhood in Le Havre, so perhaps it’s not surprising that many of his early paintings are of his native Normandy. The meandering medieval streets of towns and villages on the Seine estuary, such as the lovely port of Honfleur, were an obvious choice for an aspiring artist.

Such subjects were hardly revolutionary, but paintings of recognisable spots described in contemporary guidebooks as ‘picturesque’ were likely to be saleable. And when Monet moved with his family to the small Seine village of Vétheuil in 1878, the first thing he did was turn his attention to its unexpectedly grand medieval church with a Renaissance façade, which dominated the homes clustered around it.

He painted the roads leading up to the church and views of the whole village seen from the opposite river bank, showing it colourfully reflected in the water on a brilliantly sunny day or reduced to shades of grey in the snow.

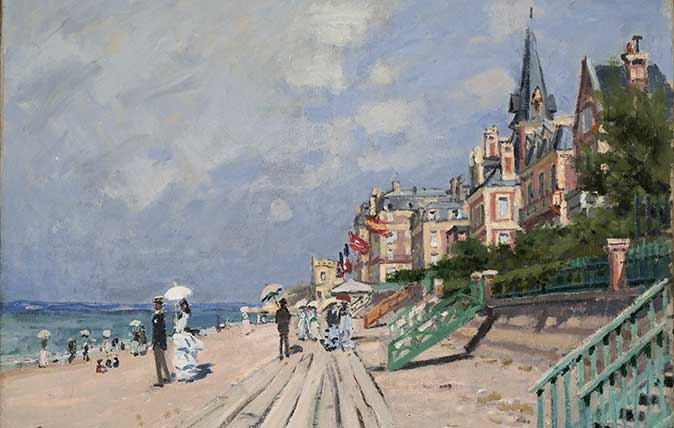

As he travelled back and forth from the Normandy coast, he would also paint the fashionable resort of Trouville with its boardwalk bustling with well-to-do holidaymakers, smart new hotel and imposing villas. A lonely hut that belonged to a customs officer, perched on the cliffs near Pourville and dwarfed by the vastness of a marine landscape, struck a different note, looking out to sea like a coastguard keeping watch.

Like thousands of other tourists, Monet took advantage of the new railways to go further afield, travelling south in search of the picturesque in the 1880s. He spent some weeks on the Italian Riviera at Bordighera, and in the south of France, at Antibes. There he painted distant vistas of the ancient towns, with campaniles and castles bathed in warm sunlight and cosily ensconced in lush countryside against mountainous backdrops.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The counterparts to all these picturesque views are the paintings in which Monet focuses on the distinctly modern aspects of cities. His views of Paris inevitably included many of the city’s famous monuments, but he did not edit out quirky contemporary features such as kiosks, advertising hoardings and gas lamps.

On a public holiday in 1878, he negotiated his way into an apartment on rue Montorgeuil, where from its balcony he could look down on buildings bedecked with flags and the boisterous crowds milling about below, capturing their movement in swift dabs of paint.

He painted the busy industrial ports of Rouen and Le Havre – nondescript suburbs with their railway bridges and factory chimneys – and the railway station of Saint Lazare through which commuters poured into the capital.

Monet was fascinated by the way that steam from the locomotives rose up to the glass roof of Saint-Lazare’s terminus like man-made clouds and he frequently veiled his urban panoramas in snow or mist.

His views of London, painted around the turn of the century, were often blanketed in the city’s famous smog, a by-product of its industry. He exploited the subtle ways in which it refracted light and created the most extraordinary chromatic effects, shrouding the towers and pinnacles of the medieval-looking Palace of Westminster in mystery.

Appearances were deceptive, though, for when Monet first saw them, the Palace and Embankment were completely new, having only been completed in 1870. Waterloo Bridge and the Pool of London, which he painted further downstream, were further evidence of modernity and commerce.

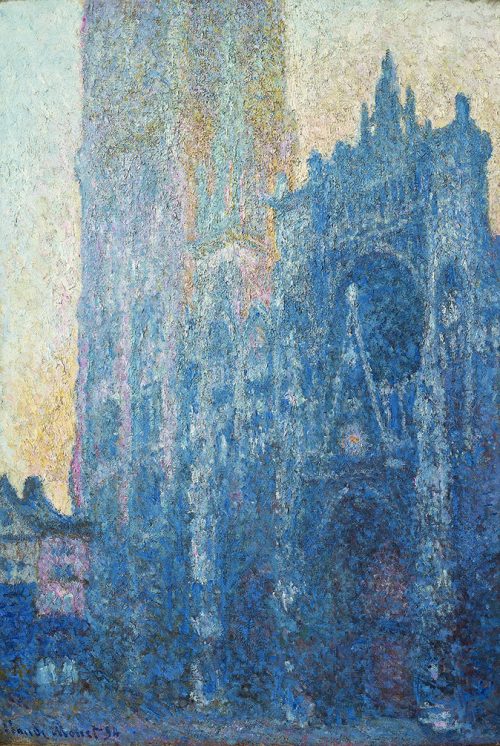

A number of Monet’s London views are still on show in Tate Britain’s ‘The Impressionists in London’, but there are eight more here, hanging near paintings from the great series of Rouen Cathedral that he produced between 1892 and 1895. Installing himself in a makeshift studio opposite the great Gothic west façade, he would work on nine or 10 canvases at once, recording its changing aspect at different times of day.

His urban scenes are usually painted from a distance, but here the view is close up. The delicate filigree of the stonework, the sculptures and tracery of the great rose window are merely suggested rather than depicted in detail, bearing out his confession that he ‘wanted to do architecture without doing its features, without the lines’.

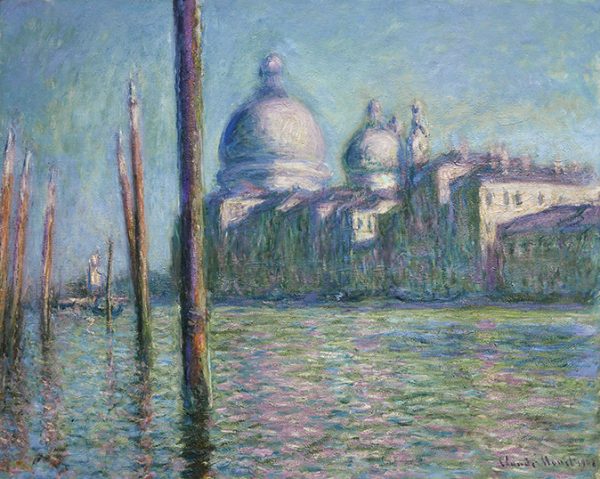

The encrusted surfaces of the Rouen canvases look almost like crumbling cliff faces full of indentations and crevices and the same sense that architecture is somehow organic can be felt in the late Venetian scenes on show here.

The Doge’s Palace appears like a sea monster rising out of the lagoon and patrician mansions seem to dissolve into the Grand Canal. Ancient monuments redolent of past grandeur were perfect screens on which to project the fleeting effects of light and weather or watery reflection. After all, as Monet said, ‘Everything changes, even stone.’

‘The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Monet & Architecture’ is at the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, London, until July 29. See www.nationalgallery.org.uk/monet for more details. £20 weekdays, £22 weekends, children and members free.

Credit: Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973): <i>Girl Before a Mirror </i>(Boisgeloup, March 1932). New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

In Focus: The Picasso portrait which revealed to the world his 22-year-old muse

The Tate Modern's first-ever exhibition focusing solely on Picasso concentrates solely on a single year in the life of this

Credit: David Milne, Tent in Temagami, 1929, Collection of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario, bequest from the Douglas M. Duncan Collection, 1970. © The Estate of David Milne

In Focus: The Canadian hermit's work that is a dystopian alternative to Monet

Canadian artist David Milne moved from city to country, eventually ending up as a hermit in a remote part of

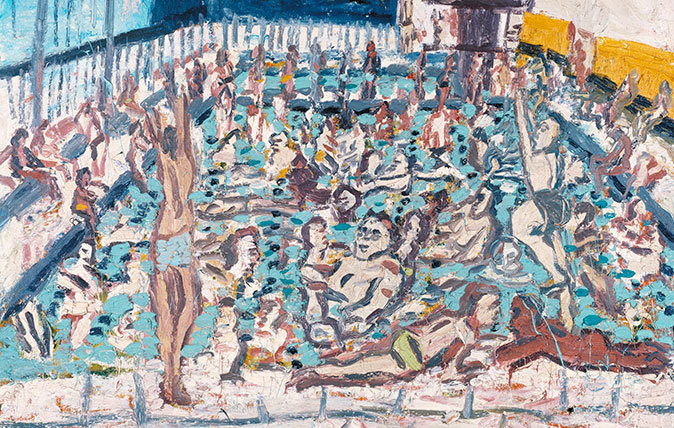

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

In Focus: The Van Dyck portrait that shows Charles I as monarch, connoisseur and proud father

Lilias Wigan takes a detailed look at Van Dyck's Greate Peece, one of the highlights of the Royal Academy's stunning

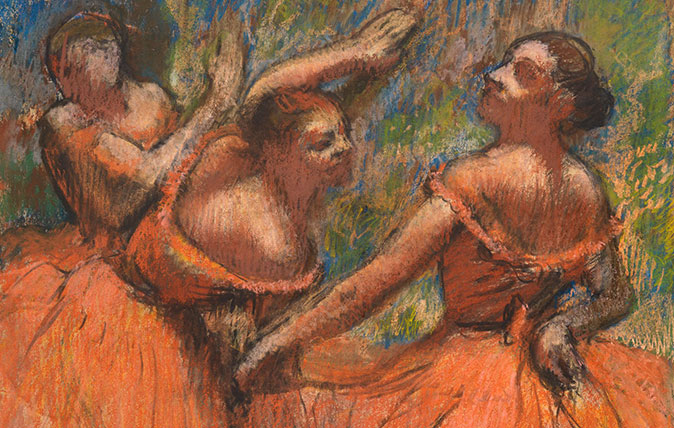

Credit: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas - The Burrell Collection, Glasgow © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

In Focus: The Degas painting full of life, movement and 'orgies of colour'

Lilias Wigan takes a closer look at one of the key work's at the Degas exhibition at the National Gallery

Credit: Winifred Nicholson, Cyclamen and Primula, 1923. Oil on board, 50 x 50 cm. Image courtesy of Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

In Focus: The radiant, sunlit work by the artist who inspired the founder of Kettle's Yard

Credit: Michael Armitage, The Flaying of Marsyas, 2017. © Michael Armitage. Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby). Courtesy of the Artist and White Cube.

In Focus: Michael Armitage's image of African violence that points the finger back at the western world

Michael Armitage's The Flaying of Marsyas is the centrepiece of his exhibition in South London. Lilias Wigan examines it in

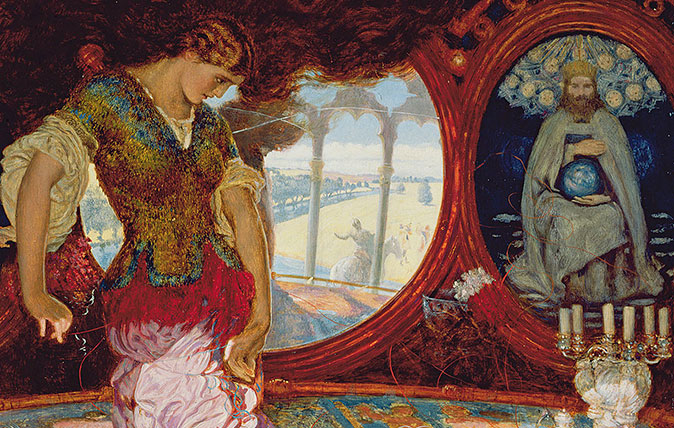

Credit: Bridgeman

In Focus: How Holman Hunt's Lady of Shallot was inspired by Van Eyck's greatest masterpiece

Holman Hunt was one of several pre-Raphaelites inspired by Jan Van Eyck's iconic The Arnolfini Portrait. Lilias Wigan takes an

In Focus: Cézanne's brutally honest portrait of his wife, 'weary and dissatisfied', as their relationship was on the rocks

The National Portrait Gallery's exhibition of portraits by Paul Cézanne comes to an end this weekend. Lilias Wigan takes an

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's Breath

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's BreathBy Carla Passino